October Revolution of 1917. Chronicle of events

Editor's responseOn the night of October 25, 1917, an armed uprising began in Petrograd, during which the current government was overthrown and power was transferred to the Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. The most important objects were captured - bridges, telegraphs, government offices, and at 2 a.m. on October 26, the Winter Palace was taken and the Provisional Government was arrested.

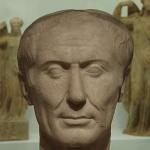

V. I. Lenin. Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

Prerequisites for the October Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917, which was greeted with enthusiasm, although it put an end to the absolute monarchy in Russia, very soon disappointed the revolutionary-minded “lower strata” - the army, workers and peasants, who expected it to end the war, transfer land to the peasants, ease working conditions for workers and democratic power devices. Instead, the Provisional Government continued the war, assuring the Western allies of their fidelity to their obligations; in the summer of 1917, on his orders, a large-scale offensive began, which ended in disaster due to the collapse of discipline in the army. Attempts to carry out land reform and introduce an 8-hour working day in factories were blocked by the majority in the Provisional Government. Autocracy was not completely abolished - the question of whether Russia should be a monarchy or a republic was postponed by the Provisional Government until convening Constituent Assembly. The situation was also aggravated by the growing anarchy in the country: desertion from the army assumed gigantic proportions, unauthorized “redistributions” of land began in villages, and thousands of landowners’ estates were burned. Poland and Finland declared independence, nationally minded separatists claimed power in Kyiv, and their own autonomous government was created in Siberia.

Counter-revolutionary armored car "Austin" surrounded by cadets at the Winter Palace. 1917 Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

At the same time, a powerful system of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies emerged in the country, which became an alternative to the bodies of the Provisional Government. Soviets began to form during the 1905 revolution. They were supported by numerous factory and peasant committees, police and soldiers' councils. Unlike the Provisional Government, they demanded an immediate end to the war and reforms, which found increasing support among the embittered masses. The dual power in the country becomes obvious - the generals in the person of Alexei Kaledin and Lavr Kornilov demand the dispersal of the Soviets, and the Provisional Government in July 1917 carried out mass arrests of deputies of the Petrograd Soviet, and at the same time demonstrations took place in Petrograd under the slogan “All power to the Soviets!”

Armed uprising in Petrograd

The Bolsheviks headed for an armed uprising in August 1917. On October 16, the Bolshevik Central Committee decided to prepare an uprising; two days after this, the Petrograd garrison declared disobedience to the Provisional Government, and on October 21, a meeting of representatives of the regiments recognized the Petrograd Soviet as the only legitimate authority. From October 24, troops of the Military Revolutionary Committee occupied key points in Petrograd: train stations, bridges, banks, telegraphs, printing houses and power plants.

The Provisional Government was preparing for this station, but the coup that took place on the night of October 25 came as a complete surprise to him. Instead of the expected mass demonstrations of the garrison regiments, detachments of the working Red Guard and sailors of the Baltic Fleet simply took control of key objects - without firing a single shot, putting an end to dual power in Russia. On the morning of October 25, only the Winter Palace, surrounded by Red Guard detachments, remained under the control of the Provisional Government.

At 10 a.m. on October 25, the Military Revolutionary Committee issued an appeal in which it announced that all “state power had passed into the hands of the body of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.” At 21:00, a blank shot from the Baltic Fleet cruiser Aurora signaled the start of the assault on the Winter Palace, and at 2 a.m. on October 26, the Provisional Government was arrested.

Cruiser Aurora". Photo: Commons.wikimedia.org

On the evening of October 25, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets opened in Smolny, proclaiming the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

On October 26, the congress adopted the Decree on Peace, which invited all warring countries to begin negotiations on the conclusion of a general democratic peace, and the Decree on Land, according to which the land of the landowners was to be transferred to the peasants, and all mineral resources, forests and waters were nationalized.

The congress also formed a government, the Council of People's Commissars headed by Vladimir Lenin - the first highest body of state power Soviet Russia.

On October 29, the Council of People's Commissars adopted the Decree on the eight-hour working day, and on November 2, the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, which proclaimed the equality and sovereignty of all peoples of the country, the abolition of national and religious privileges and restrictions.

On November 23, a decree “On the abolition of estates and civil ranks” was issued, proclaiming the legal equality of all citizens of Russia.

Simultaneously with the uprising in Petrograd on October 25, the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Moscow Council also took control of all important strategic facilities in Moscow: the arsenal, telegraph, National Bank etc. However, on October 28, the Committee of Public Security, headed by the Chairman of the City Duma Vadim Rudnev, with the support of cadets and Cossacks, began military action against the Council.

Fighting in Moscow continued until November 3, when the Committee of Public Security agreed to lay down arms. The October Revolution was immediately supported in the Central Industrial Region, where local Soviets of Workers' Deputies had already effectively established their power; in the Baltics and Belarus, Soviet power was established in October - November 1917, and in the Central Black Earth Region, the Volga region and Siberia, the process of recognition of Soviet power dragged on until the end of January 1918.

Name and celebration of the October Revolution

Since Soviet Russia switched to the new Gregorian calendar in 1918, the anniversary of the Petrograd uprising fell on November 7. But the revolution was already associated with October, which was reflected in its name. This day became an official holiday in 1918, and starting from 1927, two days became holidays - November 7 and 8. Every year on this day, demonstrations and military parades took place on Red Square in Moscow and in all cities of the USSR. The last military parade on Moscow's Red Square to commemorate the anniversary of the October Revolution took place in 1990. Since 1992, November 8 became a working day in Russia, and in 2005, November 7 was also abolished as a day off. Until now, the Day of the October Revolution is celebrated in Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Transnistria.

Plan

Revolution of 1917 in Russia

February Revolution

Policy of the Provisional Government

From February to October

October Revolution

The Bolsheviks came to power

II Congress of Soviets

Revolution of 1917 in Russia

Russia's entry into the first world war for some time the severity of social contradictions was removed. All segments of the population rallied around the government in a single patriotic impulse. The defeat at the front in the fight against Germany, the worsening situation of the people caused by the war, gave rise to mass discontent.

The situation was aggravated by the economic crisis that emerged in 1915-1916. Industry, rebuilt on a war footing, generally provided for the needs of the front. However, its one-sided development led to the fact that the rear suffered from a shortage of consumer goods. The consequence of this was an increase in prices and an increase in inflation: the purchasing power of the ruble fell to 27 kopecks. Fuel and transport crises developed. The capacity of the railways did not ensure military transportation and uninterrupted delivery of food to the city. The food crisis turned out to be especially acute. The peasants, not receiving the necessary industrial goods, refused to supply the products of their farms to the market. Bread lines appeared for the first time in Russia. Speculation flourished. The defeat of Russia on the fronts of the First World War dealt a significant blow to public consciousness. The population is tired of the protracted war. Worker strikes and peasant unrest grew. At the front, fraternization with the enemy and desertion became more frequent. Revolutionary agitators used all the government's mistakes to discredit the ruling elite. The Bolsheviks wanted the defeat of the tsarist government and called on the people to turn the war from an imperialist one into a civil one.

The liberal opposition intensified. The confrontation between the State Duma and the government intensified. The basis of the June Third political system, cooperation between bourgeois parties and the autocracy, collapsed. Speech by N.N. Miliukov on November 4, 1916, with sharp criticism of the policies of the tsar and ministers, marked the beginning of an “accusatory” campaign in the IV State Duma. The “Progressive Bloc” - an inter-parliamentary coalition of the majority of Duma factions - demanded the creation of a government of “people's trust” responsible to the Duma. However, Nicholas II rejected this proposal.

Nicholas II catastrophically lost authority in society due to “Rasputinism,” the unceremonious intervention of Tsarina Alexander Feodorovna in state affairs and his inept actions as Supreme Commander-in-Chief. By the winter of 1916-1917. All segments of the Russian population realized the inability of the tsarist government to overcome the political and economic crisis.

February revolution.

At the beginning of 1917, interruptions in food supplies to major Russian cities intensified. By mid-February, 90 thousand Petrograd workers went on strike due to a shortage of speculative bread and rising prices. On February 18, workers from the Putilov plant joined them. The administration announced its closure. This was the reason for the start of mass protests in the capital.

On February 23 (new style - March 8), workers took to the streets of Petrograd with the slogans “Bread!”, “Down with war!”, “Down with autocracy!” Their political demonstration marked the beginning of the Revolution. On February 25, the strike in Petrograd became general. Demonstrations and rallies did not stop.

On the evening of February 25, Nicholas II, who was in Mogilev, sent the commander of the Petrograd Military District S.S. A telegram to Khabalov with a categorical demand to stop the unrest. Attempts by the authorities to use troops did not produce a positive effect; the soldiers refused to shoot at the people. However, officers and police killed more than 150 people on February 26th. In response, the guards of the Pavlovsk regiment, supporting the workers, opened fire on the police.

Chairman of the Duma M.V. Rodzianko warned Nicholas II that the government was paralyzed and “there is anarchy in the capital.” To prevent the development of the revolution, he insisted on the immediate creation of a new government headed by a statesman who enjoyed the trust of society. However, the king rejected his proposal.

Moreover, he and the Council of Ministers decided to interrupt the meeting of the Duma and dissolve it for the holidays. Nicholas II sent troops to suppress the revolution, but a small detachment of General N.I. Ivanov was detained and not allowed into the capital.

On February 27, the mass transition of soldiers to the side of the workers, their seizure of the arsenal and the Peter and Paul Fortress, marked the victory of the revolution.

The arrests of tsarist ministers and the formation of new government bodies began. On the same day, elections to the Petrograd Soviet of Workers' Soldiers' Deputies were held in factories and military units, drawing on the experience of 1905, when the first organs of workers' political power were born. An Executive Committee was elected to manage its activities. The Menshevik N.S. became the chairman. Chkheidze, his deputy - Socialist Revolutionary A.F. Kepensky. The Executive Committee took upon itself the maintenance of public order and the supply of food to the population. On February 27, at a meeting of leaders of Duma factions, it was decided to form a Provisional Committee of the State Duma headed by M.V. Rodzianko. The task of the committee was “Restoring state and public order” and creating a new government. The temporary committee took control of all ministries.

On February 28, Nicholas II left Headquarters for Tsarskoye Selo, but was detained on the way by revolutionary troops. He had to turn to Pskov, to the headquarters of the northern front. After consultation with the front commanders, he became convinced that there was no force to suppress the revolution. On March 2, Nicholas signed a Manifesto abdicating the throne for himself and his son Alexei in favor of his brother, Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich. However, when Duma deputies A.I. Guchkov and V.V. Shulgin brought the text of the Manifesto to Petrograd, it became clear that the people did not want a monarchy. On March 3, Mikhail abdicated the throne, declaring that the future fate of the political system in Russia should be decided by the Constituent Assembly. The 300-year rule of classes and parties ended.

The bourgeoisie, a significant part of the wealthy intelligentsia (about 4 million people) relied on economic power, education, experience in participating in political life and managing government institutions. They sought to prevent the further development of the revolution, stabilize the socio-political situation and strengthen their property. The working class (18 million people) consisted of urban and rural proletarians. They managed to feel their political strength, were predisposed to revolutionary agitation and were ready to defend their rights with weapons. They fought for the introduction of an 8-hour working day, a guarantee of employment, and increased wages. Factory committees spontaneously arose in cities. To establish workers' control over production and resolve disputes with entrepreneurs.

The peasantry (30 million people) demanded the destruction of large private land properties and the transfer of land to those who cultivate it. Local land committees and village assemblies were created in the villages, which made decisions on the redistribution of land. Relations between peasants and landowners were extremely tense.

The extreme right (monarchists, Black Hundreds) suffered a complete collapse after the February revolution.

Cadets from the opposition party became the ruling party, initially occupying key positions in the provisional government. They stood for turning Russia into a parliamentary republic. On the agrarian issue, they still advocated the purchase by the state and peasants of the landowners' lands.

The Social Revolutionaries are the most massive party. The revolutionaries proposed turning Russia into a federal republic of free nations.

The Mensheviks, the second largest and most influential party, advocated the creation of a democratic republic.

The Bolsheviks took extreme left positions. In March, the party leadership was ready to cooperate with other social forces. However, after V.I. Lenin returned from immigration, the “April Theses” program was adopted.

Policy of the provisional government.

In its declaration on March 3, the government promised to introduce political freedoms and a broad amnesty, abolish the death penalty, and prohibit all class, national and religious discrimination. However, the internal political course of the provisional government turned out to be contradictory. All the main bodies of central and local government have been preserved. Under the pressure of the masses, Nicholas II and members of his family were arrested. On July 31, Nicholas, his wife and children were sent into exile in Siberia. An Extraordinary Commission was created to investigate the activities of senior officials of the old regime. Adoption of a law introducing an 8-hour working day.

In April 1917, the first government crisis broke out. It was caused by general social tension in the country. On April 18, Miliukov addressed the Allied Powers with assurances of Russia’s determination to bring the war to a victorious end. This led to extreme indignation of the people, mass meetings and demonstrations demanding an immediate end to the war, the transfer of power to the Soviets, the resignation of Miliukov and A.I. Guchkova. On July 3-4, mass armaments and demonstrations of workers and soldiers took place in Petrograd. The slogan “All power to the Soviets” was again put forward. The demonstration was dispersed. Repressions began against the Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries, who were accused of preparing an armed seizure of power.

Measures were taken to strengthen discipline in the army, and the death penalty was restored at the front. The influence of the Petrograd and other Soviets temporarily decreased. The dual power was over. From this moment, according to V.I. Lenin, the stage of the revolution ended when power could pass to the Soviets peacefully.

From February to October.

The February Revolution was victorious. The old state system collapsed. A new political situation has emerged. However, the victory of the revolution did not prevent the further deepening of the country's crisis. Economic devastation intensified.

The time from February to October is a special period in the history of Russia. There are two stages in it.

At the first (March - early July 1917) there was a dual power, in which the provisional government was forced to coordinate all its actions with the Petrograd Soviet, which took more radical positions and had the support of the broad masses.

At the second stage (July - October 25, 1917), dual power was ended. The autocracy of the provisional government was established in the form of a coalition of the liberal bourgeoisie. However, this political alliance also failed to achieve the consolidation of society. Social tension has increased in the country. On the one hand, there was growing indignation of the masses over the government's delays in carrying out the most pressing economic, social and political reforms. On the other hand, the right was not happy with the weakness of the government and the insufficiently decisive measures to curb the “revolutionary element.” Monarchists and right-wing bourgeois parties were ready to support the establishment of a military dictatorship. The far left Bolsheviks set a course for seizing political power under the slogan “All power to the Soviets!”

October Revolution. The Bolsheviks came to power.

On October 10, the Central Committee of the RSDLP (b) adopted a resolution on an armed uprising. L.B. opposed her. Kamenev and G.E. Zinoviev. They believed that preparations for an uprising were premature and that it was necessary to fight to increase the influence of the Bolsheviks in the future Constituent Assembly. IN AND. Lenin insisted on the immediate seizure of power through an armed uprising. His point of view won.

The chairman was the left Socialist-Revolutionary P.E. Lazimir, and the actual leader is L.D. Trotsky (chairman of the Petrograd Soviet from September 1917). The Military Revolutionary Committee was created to protect the Soviets from the military coup and Petrograd. On October 16, the Central Committee of the RSDLP(b) created the Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Center (MRC). He joined the Military Revolutionary Committee and began to direct its activities. By the evening of October 24, the government was blocked in the Winter Palace.

On the morning of October 25, the appeal of the Military Revolutionary Committee “To the citizens of Russia!” was published. It announced the overthrow of the provisional government and the transfer of power to the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee. On the night of October 25-26, the ministers of the provisional government were arrested in the Winter Palace.

IICongress of Soviets.

On the evening of October 25, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets opened. More than half of its deputies were Bolsheviks, 100 mandates were from the Left Social Revolutionaries.

On the night of October 25-26, the congress adopted an appeal to workers, soldiers and peasants, and proclaimed the establishment of Soviet power. The Mensheviks and Right Socialist Revolutionaries condemned the action of the Bolsheviks and left the congress in protest. Therefore, all the decrees of the Second Congress were permeated with the ideas of the Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries.

On the evening of October 26, the congress unanimously adopted the Decree on Peace, which called on the warring parties to conclude a democratic peace without annexations and indemnities.

The October Revolution of 1917 was the armed overthrow of the Provisional Government, the accession of the Bolshevik Party to the head of the state, which proclaimed the establishment of Soviet power.

The historical significance of the October Revolution of 1917 is enormous for the country as a whole; in addition to the change of power, there was also a change in the direction in which Russia was moving, the transition from capitalism to socialism began.

Causes of the October Revolution

The October Revolution had reasons of both a subjective and objective nature. TO objective reasons can be attributed to the economic difficulties experienced by Russia due to participation in the First World War, human losses at the fronts, the pressing peasant issue, the difficult living conditions of workers, the illiteracy of the people and the mediocrity of the country's leadership.

Subjective reasons include the passivity of the population, the ideological tossing of the intelligentsia from anarchism to terrorism, the presence in Russia of a small but well-organized, disciplined group - the Bolshevik Party and the primacy in it of the great historical Personality - V. I. Lenin, as well as the absence of a person in the country the same scale.

October Revolution of 1917. Brief progress, results

This significant event for the country took place on October 25 according to the old style or November 7 according to the new style. The reason was the slowness and inconsistency of the Provisional Government in resolving agrarian, labor, and national issues after the February events, as well as Russia’s continued participation in the world war. All this aggravated the national crisis and strengthened the position of far-left and nationalist parties.

The beginning of the October Revolution of 1917 was laid at the beginning of September 1917, when the Bolsheviks took the majority in the Soviets of Petrograd and prepared an armed uprising, timed to coincide with the opening of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

On the night of October 25 (November 7), armed workers, sailors of the Baltic Fleet and soldiers of the Petrograd garrison, after being shot from the cruiser Aurora, captured the Winter Palace and took the Provisional Government under arrest. The bridges on the Neva, the Central Telegraph, the Nikolaevsky Station, the State Bank were immediately captured, military schools, etc. were blocked.

At the then Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, the overthrow of the Provisional Government and the establishment and formation of a new government - the Council of People's Commissars - were approved. This government body was supposed to work until the convening of the Constituent Assembly. It included V. Lenin (chairman); I. Teodorovich, A. Lunacharsky, N. Avilov, I. Stalin, V. Antonov. Decrees on peace and land were immediately adopted.

Having suppressed the resistance of forces loyal to the Provisional Government in Petrograd and Moscow, the Bolsheviks managed to quickly establish dominance in the main industrial cities of Russia.

The main opponent, the Cadets Party, was outlawed.

Participants of the October Revolution 1917

The initiator, ideologist and main protagonist of the revolution was the Bolshevik party RSDLP (b) (Russian Social Democratic Bolshevik Party), led by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (party pseudonym Lenin) and Lev Davidovich Bronstein (Trotsky).

Slogans of the October Revolution of 1917:

"Power to the Soviets"

"Peace to the Nations"

"Land to the peasants"

"Factory to workers"

October Revolution. Consequences. Results

The October Revolution of 1917, the consequences of which completely changed the course of history for Russia, is characterized by the following results:

- A complete change of the elite that ruled the country for 1000 years

- The Russian Empire turned into the Soviet Empire, which became one of two countries (together with the USA) that led the world community

- The Tsar was replaced by Stalin, who had more power and authority than any Russian emperor

- The ideology of Orthodoxy was replaced by communist

- An agricultural country has turned into a powerful industrial power

- Literacy has become universal

- The Soviet Union achieved the withdrawal of education and medical care from the system of commodity-money relations

- Absence of unemployment, almost complete equality of the population in income and opportunities, no division of people into poor and rich

1917 was a year of upheaval and revolution in Russia, and its finale came on the night of October 25, when all power passed to the Soviets. What are the causes, course, results of the Great October Socialist Revolution - these and other questions of history are in the center of our attention today.

Causes

Many historians argue that the events that occurred in October 1917 were inevitable and at the same time unexpected. Why? Inevitable, because by this time in Russian Empire a certain situation arose that predetermined the further course of history. This was due to a number of reasons:

- Results of the February Revolution : she was greeted with unprecedented delight and enthusiasm, which soon turned into the opposite - bitter disappointment. Indeed, the performance of the revolutionary-minded “lower classes” - soldiers, workers and peasants - led to a serious shift - the overthrow of the monarchy. But this is where the achievements of the revolution ended. The expected reforms were “hanging in the air”: the longer the Provisional Government postponed consideration of pressing problems, the faster discontent in society grew;

- Overthrow of the monarchy : March 2 (15), 1917, Russian Emperor Nicholas II signed the abdication of the throne. However, the question of the form of government in Russia - a monarchy or a republic - remained open. The Provisional Government decided to consider it during the next convocation of the Constituent Assembly. Such uncertainty could only lead to one thing - anarchy, which is what happened.

- The mediocre policy of the Provisional Government : the slogans under which the February Revolution took place, its aspirations and achievements were actually buried by the actions of the Provisional Government: Russia’s participation in the First World War continued; a majority vote in the government blocked land reform and the reduction of the working day to 8 hours; autocracy was not abolished;

- Russian participation in the First World War: any war is an extremely costly undertaking. It literally “sucks” all the juice out of the country: people, production, money - everything goes to support it. The First World War was no exception, and Russia's participation in it undermined the country's economy. After the February Revolution, the Provisional Government did not retreat from its obligations to the allies. But discipline in the army had already been undermined, and widespread desertion began in the army.

- Anarchy: already in the name of the government of that period - the Provisional Government, the spirit of the times can be traced - order and stability were destroyed, and they were replaced by anarchy - anarchy, lawlessness, confusion, spontaneity. This was manifested in all spheres of the country’s life: an autonomous government was formed in Siberia, which was not subordinate to the capital; Finland and Poland declared independence; in the villages, peasants were engaged in unauthorized redistribution of land, burning landowners' estates; the government was mainly engaged in the struggle with the Soviets for power; the disintegration of the army and many other events;

- The rapid growth of influence of the Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies : During the February Revolution, the Bolshevik party was not one of the most popular. But over time, this organization becomes the main political player. Their populist slogans about an immediate end to the war and reforms found great support among embittered workers, peasants, soldiers and police. Not the least was the role of Lenin as the creator and leader of the Bolshevik Party, which carried out the October Revolution of 1917.

Rice. 1. Mass strikes in 1917

Stages of the uprising

Before speaking briefly about the 1917 revolution in Russia, it is necessary to answer the question about the suddenness of the uprising itself. The fact is that the actual dual power in the country - the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks - should have ended with some kind of explosion and subsequent victory for one of the parties. Therefore, the Soviets began preparing to seize power back in August, and at that time the government was preparing and taking measures to prevent it. But the events that happened on the night of October 25, 1917 came as a complete surprise to the latter. The consequences of the establishment of Soviet power also became unpredictable.

Back on October 16, 1917, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party made a fateful decision - to prepare for an armed uprising.

On October 18, the Petrograd garrison refused to submit to the Provisional Government, and already on October 21, representatives of the garrison declared their subordination to the Petrograd Soviet, as the only representative of legitimate power in the country. Starting from October 24, key points in Petrograd - bridges, train stations, telegraphs, banks, power plants and printing houses - were captured by the Military Revolutionary Committee. On the morning of October 25, the Provisional Government held only one object - the Winter Palace. Despite this, at 10 o'clock in the morning of the same day, an appeal was issued, which announced that from now on the Petrograd Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was the only body of state power in Russia.

In the evening at 9 o'clock, a blank shot from the cruiser Aurora signaled the start of the assault on the Winter Palace and on the night of October 26, members of the Provisional Government were arrested.

Rice. 2. The streets of Petrograd on the eve of the uprising

Results

As you know, history does not like the subjunctive mood. It is impossible to say what would have happened if this or that event had not occurred and vice versa. Everything that happens happens as a result of not a single cause, but of many, which at one moment intersected at one point and revealed the event to the world with all its positive and negative points: civil war, a huge number of dead, millions who left the country forever, terror, building an industrial power, eliminating illiteracy, free education, medical service, building the world's first socialist state and much more. But, speaking about the main significance of the October Revolution of 1917, one thing should be said - it was a profound revolution in the ideology, economy and structure of the state as a whole, which influenced not only the course of history of Russia, but of the whole world.

Great October Socialist Revolution |

|

See Background to the October Revolution |

|

Primary goal: |

Overthrow of the Provisional Government |

Bolshevik victory Creation of the Russian Soviet Republic |

|

Organizers: |

RSDLP (b) Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets |

Driving forces: |

Workers Red Guards |

Number of participants: |

10,000 sailors 20,000 - 30,000 Red Guards |

Opponents: |

|

Dead: |

Unknown |

Those injured: |

5 Red Guards |

Arrested: |

Provisional Government of Russia |

October Revolution(full official name in the USSR -, alternative names: October Revolution, Bolshevik coup, third Russian revolution listen)) is a stage of the Russian revolution that occurred in Russia in October 1917. As a result of the October Revolution, the Provisional Government was overthrown and the government formed by the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets came to power, the absolute majority of the delegates of which were Bolsheviks - the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (Bolsheviks) and their allies the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, also supported by some national organizations, a small part Menshevik-internationalists, and some anarchists. In November, the new government was also supported by the majority of the Extraordinary Congress of Peasant Deputies.

The Provisional Government was overthrown during an armed uprising on October 25-26 (November 7-8, new style), the main organizers of which were V. I. Lenin, L. D. Trotsky, Ya. M. Sverdlov and others. The uprising was directly led by The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, which also included the Left Social Revolutionaries.

There is a wide range of assessments of the October Revolution: for some, it is a national catastrophe that led to the Civil War and the establishment of a totalitarian system of government in Russia (or, conversely, to the death of Great Russia as an empire); for others - the greatest progressive event in the history of mankind, which had a huge impact on the whole world, and allowed Russia to choose a non-capitalist path of development, eliminate feudal remnants and, in 1917, most likely saved it from disaster. Between these extreme points of view there is a wide range of intermediate ones. There are also many historical myths associated with this event.

Name

The revolution took place on October 25, 1917, according to the Julian calendar, adopted at that time in Russia, and although already in February 1918 the Gregorian calendar was introduced ( a new style) and already the first anniversary (like all subsequent ones) was celebrated on November 7-8, the revolution was still associated with October, which was reflected in its name.

From the very beginning, the Bolsheviks and their allies called the events of October a “revolution.” So, at a meeting of the Petrograd Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies on October 25 (November 7), 1917, Lenin said his famous: “Comrades! The workers’ and peasants’ revolution, the need for which the Bolsheviks were always talking about, has taken place.”

The definition of “the great October Revolution” first appeared in the declaration announced by F. Raskolnikov on behalf of the Bolshevik faction in the Constituent Assembly. By the end of the 30s of the XX century, the name was established in Soviet official historiography Great October Socialist Revolution. In the first decade after the revolution it was often called October Revolution, and this name did not carry a negative meaning (at least in the mouths of the Bolsheviks themselves) and seemed more scientific in the concept of a unified revolution of 1917. V.I. Lenin, speaking at a meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee on February 24, 1918, said: “Of course, it is pleasant and easy to talk to workers, peasants and soldiers, it was pleasant and easy to observe how after the October Revolution the revolution moved forward...”; this name can be found in L. D. Trotsky, A. V. Lunacharsky, D. A. Furmanov, N. I. Bukharin, M. A. Sholokhov; and in Stalin’s article dedicated to the first anniversary of October (1918), one of the sections was called About the October Revolution. Subsequently, the word “coup” began to be associated with conspiracy and illegal change of power (by analogy with palace coups), the concept of two revolutions was established, and the term was removed from official historiography. But the expression “October revolution” began to be actively used, already with a negative meaning, in literature critical of Soviet power: in emigrant and dissident circles, and, starting with perestroika, in the legal press.

Background

There are different versions of the premises of the October Revolution. The main ones can be considered:

- version of "two revolutions"

- version of the united revolution of 1917

Within their framework, we can, in turn, highlight:

- version of the spontaneous growth of the “revolutionary situation”

- version of the targeted action of the German government (See Sealed carriage)

Version of "two revolutions"

In the USSR, the beginning of the formation of this version should probably be attributed to 1924 - discussions about the “Lessons of October” by L. D. Trotsky. But it finally took shape during Stalin’s times and remained official until the end of the Soviet era. What in the first years of Soviet power had rather a propaganda meaning (for example, calling the October Revolution “socialist”), over time turned into a scientific doctrine.

According to this version, the bourgeois-democratic revolution began in February 1917 and was completely completed in the coming months, and what happened in October was initially a socialist revolution. The TSB said so: “The February bourgeois-democratic revolution of 1917, the second Russian revolution, as a result of which the autocracy was overthrown and conditions were created for the transition to the socialist stage of the revolution.”

Associated with this concept is the idea that the February Revolution gave the people everything they fought for (first of all, freedom), but the Bolsheviks decided to establish socialism in Russia, the prerequisites for which did not yet exist; as a result, the October Revolution turned into a “Bolshevik counter-revolution.”

The version of “targeted action of the German government” (“German financing”, “German gold”, “sealed carriage”, etc.) is essentially adjacent to it, since it also assumes that in October 1917 something happened that was not directly related to the February Revolution.

Single revolution version

While the version of “two revolutions” was taking shape in the USSR, L. D. Trotsky, already abroad, wrote a book about the single revolution of 1917, in which he defended a concept that was once common to party theorists: the October Revolution and the decrees adopted by the Bolsheviks in the first months after coming to power, were only the completion of the bourgeois-democratic revolution, the implementation of what the insurgent people fought for in February.

What they fought for

The only unconditional achievement of the February Revolution was the abdication of Nicholas II from the throne; It was too early to talk about the overthrow of the monarchy as such, since this question - whether Russia should be a monarchy or a republic - had to be decided by the Constituent Assembly. However, neither for the workers who carried out the revolution, nor for the soldiers who went over to their side, nor for the peasants who thanked the Petrograd workers in writing and orally, the overthrow of Nicholas II was not an end in itself. The revolution itself began with an anti-war demonstration of Petrograd workers on February 23 (March 8 according to the European calendar): both the city and the village, and most of all the army, were already tired of the war. But there were still unrealized demands of the revolution of 1905-1907: peasants fought for land, workers fought for humane labor legislation and a democratic form of government.

What did you find?

The war continued. In April 1917, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, leader of the cadets P. N. Milyukov, in a special note, notified the allies that Russia remained faithful to its obligations. On June 18, the army launched an offensive that ended in disaster; however, even after this the government refused to begin peace negotiations.

All attempts by the Minister of Agriculture, Social Revolutionary leader V.M. Chernov, to start agrarian reform were blocked by the majority of the Provisional Government.

The attempt by the Minister of Labor, Social Democrat M.I. Skobelev, to introduce civilized labor legislation also ended in nothing. The eight-hour working day had to be established in person, to which industrialists often responded with lockouts.

In reality, political freedoms were won (of speech, press, assembly, etc.), but they were not yet enshrined in any constitution, and the July turnaround of the Provisional Government showed how easily they can be taken away. Leftist newspapers (not just Bolshevik ones) were closed by the government; “enthusiasts” could have destroyed the printing house and dispersed the meeting without government sanction.

The people who were victorious in February created their own democratic authorities - the Councils of Workers' and Soldiers', and later peasants' deputies; only the Soviets, which relied directly on enterprises, barracks and rural communities, had real power in the country. But they, too, were not legalized by any constitution, and therefore any Kaledin could demand the dispersal of the Soviets, and any Kornilov could prepare a campaign against Petrograd for this. After the July Days, many deputies of the Petrograd Soviet and members of the Central Executive Committee - Bolsheviks, Mezhrayontsy, Left Social Revolutionaries and anarchists - were arrested on dubious or even simply absurd charges, and no one was interested in their parliamentary immunity.

The Provisional Government postponed the resolution of all pressing issues either until the end of the war, but the war did not end, or until the Constituent Assembly, the convening of which was also constantly postponed.

Version of the “revolutionary situation”

The situation that arose after the formation of the government (“too right for such a country,” according to A.V. Krivoshein), Lenin characterized as “dual power”, and Trotsky as “dual power”: the socialists in the Soviets could rule, but did not want to, “progressive bloc" in the government wanted to rule, but could not, finding itself forced to rely on the Petrograd Soviet, with which it differed in views on all issues of internal and foreign policy. The revolution developed from crisis to crisis, and the first erupted in April.

April crisis

On March 2 (15), 1917, the Petrograd Soviet allowed the self-proclaimed Provisional Committee of the State Duma to form a cabinet in which there was not a single supporter of Russia’s withdrawal from the war; Even the only socialist in the government, A.F. Kerensky, needed a revolution to win the war. On March 6, the Provisional Government published an appeal, which, according to Miliukov, “set its first task as ‘bringing the war to a victorious end’ and at the same time declared that it ‘will sacredly preserve the alliances that bind us with other powers and will steadily fulfill the agreements concluded with the allies’.” "

In response, the Petrograd Soviet on March 10 adopted a manifesto “To the peoples of the whole world”: “In the consciousness of its revolutionary strength, Russian democracy declares that it will by all means oppose the imperialist policy of its ruling classes, and it calls on the peoples of Europe to make joint decisive actions in favor of peace.” . On the same day, a Contact Commission was created - partly to strengthen control over government actions, partly to seek mutual understanding. As a result, a declaration of March 27 was developed, which satisfied the majority of the Council.

Public debate on the issue of war and peace ceased for some time. However, on April 18 (May 1), Miliukov, under pressure from the allies who demanded clear statements about the government’s position, wrote a note (published two days later) as a commentary to the declaration of March 27, which spoke of “the national desire to bring the world war to a decisive victory.” and that the Provisional Government “will fully comply with the obligations assumed in relation to our allies.” The left Menshevik N. N. Sukhanov, the author of the March agreement between the Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Committee of the State Duma, believed that this document “finally and officially” signed “the complete falsity of the declaration of March 27, the disgusting deception of the people by the ‘revolutionary’ government.”

Such a statement on behalf of the people was not slow to cause an explosion. On the day of its publication, April 20 (May 3), a non-partisan ensign of the reserve battalion of the Finnish Guard Regiment, a member of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Council, F. F. Linde, without the knowledge of the Council, led the Finnish Regiment onto the street, "whose example was immediately followed by other military units of Petrograd and the surrounding area.

An armed demonstration in front of the Mariinsky Palace (the seat of government) under the slogan “Down with Milyukov!”, and then “Down with the Provisional Government!” lasted two days. On April 21 (May 4), Petrograd workers took an active part in it and posters appeared “All power to the Soviets!” Supporters of the “progressive bloc” responded to this with demonstrations in support of Miliukov. “The note of April 18,” reports N. Sukhanov, “shaken more than one capital. Exactly the same thing happened in Moscow. Workers abandoned their machines, soldiers abandoned their barracks. The same rallies, the same slogans - for and against Miliukov. The same two camps and the same cohesion of democracy...”

The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, unable to stop the demonstrations, demanded an explanation from the government, which was given. In the resolution of the Executive Committee, adopted by a majority vote (40 to 13), it was recognized that the government’s clarification, caused by the “unanimous protest of the workers and soldiers of Petrograd,” “puts an end to the possibility of interpreting the note of April 18 in a spirit contrary to the interests and demands of revolutionary democracy.” The resolution concluded by expressing confidence that “the peoples of all warring countries will break the resistance of their governments and force them to enter into peace negotiations on the basis of renouncing annexations and indemnities.”

But armed demonstrations in the capital were stopped not by this document, but by the Council’s appeal “To all citizens,” which also contained a special appeal to the soldiers:

After the proclamation was published, the commander of the Petrograd Military District, General L. G. Kornilov, who, for his part, also tried to bring troops into the streets to protect the Provisional Government, resigned, and the Provisional Government had no choice but to accept it.

July days

Feeling its instability in the days of the April crisis, the Provisional Government hastened to get rid of the unpopular Miliukov and once again turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help, inviting the socialist parties to delegate their representatives to the government.

After long and heated discussions in the Petrograd Soviet on May 5, the right-wing socialists accepted the invitation: Kerensky was appointed Minister of War, the leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries Chernov took the portfolio of the Minister of Agriculture, the Social Democrat (Menshevik) I. G. Tsereteli became the Minister of Posts and Telegraphs (later - the Minister of Internal Affairs Affairs), his party comrade Skobelev headed the Ministry of Labor and, finally, the People's Socialist A.V. Peshekhonov became the Minister of Food.

Thus, the socialist ministers were called upon to solve the most complex and most pressing problems of the revolution, and as a result, to take upon themselves the dissatisfaction of the people with the ongoing war, food shortages usual for any war, the failure to resolve the land issue and the absence of new labor legislation. At the same time, the majority of the government could easily block any socialist initiatives. An example of this is the work of the Labor Committee, in which Skobelev tried to resolve the conflict between workers and industrialists.

A number of bills were proposed for consideration by the Committee, including on freedom of strikes, an eight-hour working day, restrictions on child labor, old-age and disability benefits, and labor exchanges. V. A. Averbakh, who represented industrialists in the Committee, said in his memoirs:

As a result of either the eloquence or the sincerity of the industrialists, only two bills were adopted - on stock exchanges and on sickness benefits. “Other projects, subjected to merciless criticism, were sent to the cabinet of the Minister of Labor and never came out again.” Averbakh, not without pride, talks about how the industrialists managed not to concede almost an inch to their “sworn enemies,” and casually reports that all the bills they rejected (in the development of which both the Bolsheviks and Mezhrayontsy took part) “after the victory of the Bolshevik revolution were used by the Soviet government either in their original form or in the form in which they were proposed by a group of workers of the Labor Committee" ...

Ultimately, the right-wing socialists did not add popularity to the government, but they lost their own in a matter of months; “dual power” moved inside the government. At the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which opened in Petrograd on June 3 (16), left socialists (Bolsheviks, Mezhrayontsy and left Socialist Revolutionaries) called on the right majority of the Congress to take power into their own hands: only such a government, they believed, could lead the country out of the permanent crisis.

But the right-wing socialists found many reasons to once again give up power; By a majority vote, the Congress expressed confidence in the Provisional Government.

Historian N. Sukhanov notes that the mass demonstration that took place on June 18 in Petrograd demonstrated a significant increase in the influence of the Bolsheviks and their closest allies, the Mezhrayontsy, primarily among Petrograd workers. The demonstration took place under anti-war slogans, but on the same day Kerensky, under pressure from the allies and domestic supporters of continuing the war, launched a poorly prepared offensive at the front.

According to the testimony of Central Executive Committee member Sukhanov, since June 19 there was “anxiety” in Petrograd, “the city felt like it was on the eve of some kind of explosion”; newspapers printed rumors about how the 1st Machine Gun Regiment was conspiring with the 1st Grenadier Regiment to jointly act against the government; Trotsky claims that not only the regiments conspired among themselves, but also the factories and barracks. The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet issued appeals and sent agitators to factories and barracks, but the authority of the right-wing socialist majority of the Soviet was undermined by active support for the offensive; “Nothing came of the agitation, of going to the masses,” states Sukhanov. More authoritative Bolsheviks and Mezhrayontsy called for patience... Nevertheless, the explosion occurred.

Sukhanov connects the performance of the rebel regiments with the collapse of the coalition: on July 2 (15), four cadet ministers left the government - in protest against the agreement concluded by the government delegation (Tereshchenko and Tsereteli) with the Ukrainian Central Rada: concessions to the separatist tendencies of the Rada were “the last straw, the cup overflowing." Trotsky believes that the conflict over Ukraine was just an excuse:

According to the modern historian Ph.D. V. Rodionov claims that the demonstrations on July 3 (16) were organized by the Bolsheviks. However, in 1917 the Special Commission of Investigation could not prove this. On the evening of July 3, many thousands of armed soldiers of the Petrograd garrison and workers of capital enterprises with the slogans “All power to the Soviets!” and “Down with capitalist ministers!” surrounded the Tauride Palace, the headquarters of the Central Executive Committee elected by the congress, demanding that the Central Executive Committee finally take power into its own hands. Inside the Tauride Palace, at an emergency meeting, the left socialists asked their right comrades for the same thing, seeing no other way out. Throughout July 3 and 4, more and more military units and capital enterprises joined the demonstration (many workers went to the demonstration with their families), and sailors from the Baltic Fleet arrived from the surrounding area.

Accusations of the Bolsheviks in an attempt to overthrow the government and seize power are refuted by a number of facts that were not disputed by a cadet eyewitness: the demonstrations took place precisely in front of the Tauride Palace; no one encroached on the Mariinsky Palace, where the government was meeting (“they somehow forgot about the Provisional Government,” testifies Miliukov), although it was not difficult to take it by storm and arrest the government; On July 4, it was the 176th regiment, loyal to the Mezhrayontsy, that guarded the Tauride Palace from possible excesses on the part of the demonstrators; members of the Central Executive Committee Trotsky and Kamenev, Zinoviev, whom, unlike the leaders of the right socialists, the soldiers still agreed to listen to, called on the demonstrators to disperse after they had demonstrated their will…. And gradually they dispersed.

But there was only one way to persuade workers, soldiers and sailors to stop the demonstration: by promising that the Central Election Commission would resolve the issue of power. The right-wing socialists did not want to take power into their own hands, and, by agreement with the government, the leadership of the Central Election Commission called reliable troops from the front to restore order in the city.

V. Rodionov claims that the Bolsheviks provoked the clashes by placing their riflemen on the roofs, who began firing machine guns at the demonstrators, while the Bolshevik machine gunners inflicted the greatest damage on both the Cossacks and the demonstrators. However, this opinion is not shared by other historians.

Kornilov's speech

After the entry of troops, first the Bolsheviks, then the Mezhrayontsy and Left Socialist-Revolutionaries were accused of attempting an armed overthrow of the existing government and collaborating with Germany; Arrests and extrajudicial street killings began. In not a single case was the charge proven, not a single accused was brought to trial, although, with the exception of Lenin and Zinoviev, who were hiding underground (who, at worst, could have been convicted in absentia), all the accused were arrested. Even the moderate socialist, Minister of Agriculture Viktor Chernov, did not escape accusations of collaboration with Germany; however, the decisive protest of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, with which the government still had to reckon, quickly turned the Chernov affair into a “misunderstanding.”

On July 7 (20), the head of the government, Prince Lvov, resigned, and Kerensky became minister-chairman. The new coalition government he formed set about disarming the workers and disbanding the regiments that not only participated in the July demonstrations, but also otherwise expressed their sympathies with the left socialists. Order was restored in Petrograd and its environs; it was more difficult to restore order in the country.

Desertion from the army, which began in 1915 and by 1917 reached, according to official data, 1.5 million, did not stop; Tens of thousands of armed people roamed the country. The peasants, who did not wait for the decree on land, began to arbitrarily seize lands, especially since many of them remained unsown; Conflicts in the countryside increasingly took on an armed character, and there was no one to suppress local uprisings: the soldiers sent to pacify them, most of them peasants, who also craved land, increasingly went over to the side of the rebels. If in the first months after the revolution the soviets could still restore order “with one stroke of the pen” (like the Petrograd Soviet in the days of the April crisis), then by mid-summer their authority was undermined. Anarchy was growing in the country.

The situation at the front also worsened: German troops successfully continued the offensive that had begun back in July, and on the night of August 21 (September 3), the 12th Army, at the risk of being surrounded, left Riga and Ust-Dvinsk and retreated to Wenden; Neither the death penalty at the front and the “military revolutionary courts” at the divisions, introduced by the government on July 12, nor Kornilov’s barrage detachments helped.

While the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution were accused of overthrowing the “legitimate” government, the Provisional Government itself was well aware of its illegality. It was created by the Provisional Committee of the State Duma, but no provisions on the Duma gave it the right to form a government, did not provide for the creation of temporary committees with exclusive rights, and the term of office of the IV State Duma, elected in 1912, expired in 1917. The government existed at the mercy of the Soviets and depended on them. But this dependence became increasingly painful: intimidated and quiet after the July Days, realizing that after the massacre of left-wing socialists it would be the turn of the right, the Soviets were more hostile than ever before. Friend and chief adviser B. Savinkov suggested to Kerensky a bizarre way to free himself from this dependence: to rely on the army in the person of General Kornilov, popular in right-wing circles - who, however, according to eyewitnesses, from the very beginning did not understand why he should serve as a support for Kerensky, and believed that “the only outcome... is the establishment of a dictatorship and the declaration of the entire country under martial law.” Kerensky requested fresh troops from the front, a corps of regular cavalry led by a liberal general; Kornilov sent Cossack units of the 3rd Cavalry Corps and the Native (“Wild”) Division to Petrograd under the command of the not at all liberal Lieutenant General A. M. Krymov. Suspecting something was wrong, Kerensky removed Kornilov from the post of commander-in-chief on August 27, ordering him to surrender his powers to the chief of staff; Kornilov refused to acknowledge his resignation; in order No. 897 issued on August 28, Kornilov stated: “Taking into account that in the current situation, further hesitation is mortally dangerous and that it is too late to cancel the preliminary orders given, I, conscious of all the responsibility, decided not to surrender the position of Supreme Commander-in-Chief in order to save the Motherland from the inevitable death, and the Russian people from German slavery.” The decision, made, as Miliukov claims, “in secret from those who had the immediate right to participate in it,” for many sympathizers, starting with Savinkov, made further support for Kornilov impossible: “Deciding to “come out openly” to “pressure” the government, Kornilov barely did he understand what this step is called in the language of the law and under what article of the criminal code his action can be brought”

Even on the eve of the rebellion, on August 26, another government crisis broke out: the Cadet ministers, who sympathized, if not with Kornilov himself, then with his cause, resigned. The government had no one to turn to for help except the Soviets, who understood perfectly well that the “irresponsible organizations” constantly mentioned by the general, against which vigorous measures should be taken, were precisely the Soviets.

But the Soviets themselves were strong only with the support of the Petrograd workers and the Baltic Fleet. Trotsky tells how on August 28, the sailors of the cruiser "Aurora", called upon to guard the Winter Palace (where the government moved after the July days), came to him at "Kresty" to consult: is it worth protecting the government - is it time to arrest it? Trotsky considered that it was not time, however, the Petrograd Soviet, in which the Bolsheviks did not yet have a majority, but had already become impact force, thanks to his influence among the workers and in Kronstadt, sold his help dearly, demanding the arming of the workers - in case it came to fighting in the city - and the release of arrested comrades. The government satisfied the second demand halfway, agreeing to release those arrested on bail. However, with this forced concession, the government actually rehabilitated them: release on bail meant that if those arrested had committed any crimes, then, in any case, not serious ones.

It didn’t come to fighting in the city: the troops were stopped at the distant approaches to Petrograd without firing a single shot.

Subsequently, one of those who was supposed to support Kornilov’s speech in Petrograd itself, Colonel Dutov, said about the “armed uprising of the Bolsheviks”: “Between August 28 and September 2, under the guise of the Bolsheviks, I was supposed to speak out... But I ran to the economic club to call go outside, but no one followed me.”

The Kornilov mutiny, more or less openly supported by a significant part of the officers, could not help but aggravate the already complex relationships between soldiers and officers - which, in turn, did not contribute to the unity of the army and allowed Germany to successfully develop the offensive).

As a result of the rebellion, the workers who had been disarmed in July found themselves armed again, and Trotsky, who was released on bail, headed the Petrograd Soviet on September 25. However, even before the Bolsheviks and Left Socialist Revolutionaries gained a majority, on August 31 (September 12), the Petrograd Soviet adopted the resolution proposed by the Bolsheviks on the transfer of power to the Soviets: almost all non-party deputies voted for it. More than a hundred local councils adopted similar resolutions on the same day or the next, and on September 5 (18), Moscow also spoke in favor of transferring power to the Soviets.

On September 1 (13), by a special government act signed by Chairman Minister Kerensky and Minister of Justice A. S. Zarudny, Russia was proclaimed a Republic. The provisional government did not have the authority to determine the form of government; the act, instead of enthusiasm, caused bewilderment and was perceived - equally by both the left and the right - as a bone thrown to the socialist parties, which at that time were clarifying the role of Kerensky in the Kornilov rebellion.

Democratic Caucus and Pre-Parliament

It was not possible to rely on the army; The Soviets moved to the left, despite any repressions against left-wing socialists, and partly thanks to them, especially noticeably after Kornilov’s speech, and became an unreliable support even for right-wing socialists. The government (more precisely, the Directory that temporarily replaced it) was subjected to harsh criticism from both the left and the right: the socialists could not forgive Kerensky for trying to come to terms with Kornilov, the right could not forgive the betrayal.

In search of support, the Directory met the initiative of the right-wing socialists - members of the Central Executive Committee, who convened the so-called Democratic Conference. The initiators invited representatives of political parties, public organizations and institutions of their own choosing and least of all observing the principle of proportional representation; Such a top-down, corporate representation, even smaller than the Soviets (elected from below by the overwhelming majority of citizens), could serve as a source of legitimate power, but could, as expected, displace the Soviets on the political stage and save the new government from having to apply for sanction to the Central Executive Committee.

The Democratic Conference, which opened on September 14 (27), 1917, at which some of the initiators hoped to form a “uniform democratic government”, and others - to create a representative body to which the government would be accountable before the Constituent Assembly, did not solve either problem, only exposed the deepest divisions in the camp of democracy. The composition of the government was eventually left to be determined by Kerensky, and the Provisional Council of the Russian Republic (Pre-Parliament) during the discussions turned from a supervisory body into an advisory one; and in composition it turned out to be much to the right of the Democratic Conference.

The results of the Conference could not satisfy either the left or the right; the weakness of democracy demonstrated at it only added arguments to both Lenin and Miliukov: both the leader of the Bolsheviks and the leader of the Cadets believed that there was no room left for democracy in the country - both because the growing anarchy objectively required strong power, and because the whole the course of the revolution only intensified the polarization in society (as was shown by the municipal elections held in August-September). The collapse of industry continued, the food crisis worsened; the strike movement had been growing since the beginning of September; Serious “unrest” arose in one region or another, and soldiers increasingly became the initiators of the unrest; The situation at the front became a source of constant anxiety. On September 25 (October 8), a new coalition government was formed, and on September 29 (October 12), the Moonsund operation of the German fleet began, ending on October 6 (19) with the capture of the Moonsund archipelago. Only the heroic resistance of the Baltic Fleet, which raised red flags on all its ships on September 9, did not allow the Germans to advance further. The half-starved and half-dressed army, according to the commander of the Northern Front, General Cheremisov, selflessly endured hardships, but the approaching autumn cold threatened to put an end to this long-suffering. Unfounded rumors that the government was going to move to Moscow and surrender Petrograd to the Germans added fuel to the fire.

In this situation, on October 7 (20), the Pre-Parliament opened in the Mariinsky Palace. At the very first meeting, the Bolsheviks, having announced their declaration, defiantly left it.

The main issue that the Pre-Parliament had to deal with throughout its short history was the state of the army. The right-wing press claimed that the Bolsheviks were corrupting the army with their agitation; in the Pre-Parliament they talked about something else: the army was poorly supplied with food, experienced an acute shortage of uniforms and shoes, did not understand and never understood the goals of the war; War Minister A.I. Verkhovsky found the program for the improvement of the army, developed even before the Kornilov speech, unfeasible, and two weeks later, against the backdrop of new defeats on the Dvina bridgehead and on the Caucasian front, he concluded that the continuation of the war was impossible in principle. P. N. Milyukov testifies that Verkhovsky’s position was shared even by some leaders of the party of constitutional democrats, but “the only alternative would have been a separate peace... and then no one wanted to agree to a separate peace, no matter how clear it was that it was possible to cut the hopelessly tangled knot If only we could get out of the war.”

The peace initiatives of the Minister of War ended with his resignation on October 23. But the main events took place far from the Marinsky Palace, at the Smolny Institute, where the government evicted the Petrograd Soviet and the Central Executive Committee at the end of July. “The workers,” Trotsky wrote in his “History,” “striked layer after layer, contrary to the warnings of the party, councils, and trade unions. Only those sections of the working class that were already consciously moving towards a revolution did not enter into conflicts. Petrograd, perhaps, remained the calmest place.”

Version of "German financing"

Already in 1917, there was an idea that the German government, interested in Russia’s exit from the war, purposefully organized the move from Switzerland to Russia of representatives of the radical faction of the RSDLP led by Lenin in the so-called. "sealed carriage". In particular, S.P. Melgunov, following Miliukov, argued that the German government, through A.L. Parvus, financed the activities of the Bolsheviks aimed at undermining the combat effectiveness of the Russian army and disorganizing the defense industry and transport. Already in exile, A. F. Kerensky reported that back in April 1917, the French Socialist Minister A. Thomas conveyed information to the Provisional Government about the connections of the Bolsheviks with the Germans; the corresponding charge was brought against the Bolsheviks in July 1917. And at present, many domestic and foreign researchers and writers adhere to this version.

Some confusion is brought into it by the idea of L. D. Trotsky as an Anglo-American spy, and this problem also goes back to the spring of 1917, when reports appeared in the cadet “Rech” that, while in the USA, Trotsky received 10 000 either marks or dollars. This idea explains the disagreements between Lenin and Trotsky regarding the Brest-Litovsk Peace (the Bolshevik leaders received money from different sources), but leaves open the question: whose action was the October Revolution, to which Trotsky, as chairman of the Petrograd Soviet and the de facto leader of the Military Revolutionary Committee, had the most direct relationship?

Historians have other questions about this version. Germany needed to close the eastern front, and God himself ordered it to support the opponents of the war in Russia - does it automatically follow from this that the opponents of the war served Germany and had no other reason to seek an end to the “world carnage”? The Entente states, for their part, were vitally interested in both preserving and intensifying the eastern front and supported by all means in Russia the supporters of “war to a victorious end” - following the same logic, why not assume that the opponents of the Bolsheviks were inspired by “gold” of a different origin, and not at all the interests of Russia?. All parties needed money, all self-respecting parties had to spend considerable funds on agitation and propaganda, on election campaigns (there were many elections at various levels in 1917), etc., etc. - and all countries involved in the First World War had their interests in Russia; but the question of sources of financing for defeated parties no longer interests anyone and remains practically unexplored.

In the early 90s, the American historian S. Lyanders discovered documents in Russian archives confirming that in 1917 members of the Foreign Bureau of the Central Committee received cash subsidies from the Swiss socialist Karl Moor; it later turned out that the Swiss was a German agent. However, the subsidies amounted to only 113,926 Swiss crowns (or $32,837), and even those were used abroad to organize the 3rd Zimmerwald Conference. So far this is the only documentary evidence of the Bolsheviks receiving “German money”.

As for A.L. Parvus, it is generally difficult to separate German money from non-German money in his accounts, since by 1915 he himself was already a millionaire; and if his involvement in the financing of the RSDLP (b) had been proven, it would also have to be specially proven that it was German money that was used, and not Parvus’s personal savings.

Serious historians are more interested in another question: what role could it have played in the events of 1917? financial aid(or other patronage) from one side or the other?

The collaboration of the Bolsheviks with the German General Staff is intended to be proven by the “sealed carriage” in which a group of Bolsheviks led by Lenin traveled through Germany. But a month later, along the same route, thanks to the mediation of R. Grimm, which Lenin refused, two more “sealed cars”, with Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, followed - but not all parties were helped by the supposed patronage of the Kaiser to win.

The intricate financial affairs of the Bolshevik Pravda allow us to assert or assume that interested Germans provided assistance to it; but despite any funding, Pravda remained a “small newspaper” (D. Reed tells how on the night of the coup the Bolsheviks seized the printing house of Russkaya Volya and for the first time printed their newspaper in a large format), which after the July Days was constantly closed and forced to change Name; dozens of large newspapers carried out anti-Bolshevik propaganda - why was the little Pravda stronger?

The same applies to all the Bolshevik propaganda, which is supposed to have been financed by the Germans: the Bolsheviks (and their internationalist allies) destroyed the army with their anti-war agitation - but much more larger number parties, which had disproportionately greater capabilities and means, at that time agitated for “war to a victorious end”, appealed to patriotic feelings, accused of betraying the workers with their demand for an 8-hour working day - why did the Bolsheviks win such an unequal battle?

A.F. Kerensky insisted on connections between the Bolsheviks and the German General Staff in 1917 and decades later; in July 1917, with his participation, a communiqué was drawn up in which “Lenin and his associates” were accused of creating a special organization “for the purpose of supporting the hostile actions of countries at war with Russia”; but on October 24, speaking for the last time in the Pre-Parliament and fully aware of his doom, he polemicized in absentia with the Bolsheviks not as German agents, but as proletarian revolutionaries: “The organizers of the uprising do not promote the proletariat of Germany, but promote ruling classes Germany, open the front of the Russian state before the armored fist of Wilhelm and his friends... For the Provisional Government, the motives are indifferent, it makes no difference whether it is conscious or unconscious, but, in any case, in the consciousness of my responsibility, from this pulpit I qualify such actions of the Russian political party as betrayal and treason to the Russian state..."

Armed uprising in Petrograd

After the July events, the government significantly renewed the Petrograd garrison, but by the end of August it already seemed unreliable, which prompted Kerensky to request troops from the front. But the troops sent by Kornilov did not reach the capital, and in early October Kerensky made a new attempt to replace the “decayed” units with those that had not yet decayed: he issued an order to send two-thirds of the Petrograd garrison to the front. The order provoked a conflict between the government and the capital’s regiments, which did not want to go to the front - from this conflict, Trotsky later claimed, the uprising actually began. Deputies of the Petrograd Council from the garrison appealed to the Council, the workers' section of which turned out to have just as little interest in the “changing of the guard.” On October 18, a meeting of representatives of the regiments, at the suggestion of Trotsky, adopted a resolution on the non-subordination of the garrison to the Provisional Government; Only those orders from the headquarters of the military district that were confirmed by the soldiers' section of the Petrograd Soviet could be executed.

Even earlier, on October 9 (22), 1917, right-wing socialists submitted to the Petrograd Soviet a proposal to create a Revolutionary Defense Committee to protect the capital from the dangerously approaching Germans; According to the initiators, the Committee was supposed to attract and organize workers for active participation in the defense of Petrograd - the Bolsheviks saw in this proposal the opportunity to legalize the workers' Red Guard and its equally legal armament and training for the coming uprising. On October 16 (29), the plenum of the Petrograd Council approved the creation of this body, but as a Military Revolutionary Committee.

The “course of armed uprising” was adopted by the Bolsheviks at the VI Congress, in early August, but at that time the party, driven underground, could not even prepare for an uprising: the workers who sympathized with the Bolsheviks were disarmed, their military organizations were destroyed, the revolutionary regiments of the Petrograd garrison were disbanded . The opportunity to arm ourselves again presented itself only during the days of the Kornilov rebellion, but after its liquidation it seemed that a new page had opened in the peaceful development of the revolution. Only on the 20th of September, after the Bolsheviks headed the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets, and after the failure of the Democratic Conference, did Lenin again talk about an uprising, and only on October 10 (23), the Central Committee, by adopting a resolution, put the uprising on the agenda. On October 16 (29), an extended meeting of the Central Committee, with the participation of representatives of the districts, confirmed the decision.