Tambov stood out for its scale and mass character: the insurgent movement covered three districts of the province, the number of participants reached 40 thousand people. The rebels acted in accordance with their own political program and were well organized.

The reasons that prompted the Tambov peasants to take up armed struggle against the communist regime have been well studied. The main one is surplus appropriation, or more precisely, the violent methods that were used during its implementation.

The food policy of the Bolsheviks, the basis of which was the forced confiscation of grain from the peasants, brought the village to the brink of physical survival. The Tambov village responded by sharply reducing crops and naturalizing its economy. If in 1918 there were 4.3 acres of crops per peasant holding in the Tambov province, then in 1920 it was only 2.8. The situation was aggravated by the shortage of food in 1920. At the same time, the food allocation for the province was set at 11.5 million poods, which was initially impossible. According to the authorities themselves, in a number of places the rural population was starving, consuming “not only quinoa and chaff, but also bark and nettles” as food. At the same time, the peasants saw that the grain seized during the allotment was rotting at the stations, drunk by Soviet leaders and distilled into moonshine. Various types of duties were added to the fire of discontent - horse-drawn, labor, etc. Thus, the uprising was provoked by the authorities themselves. For peasants, it became a form of struggle for physical survival in critical conditions.

The rural population initially responded to the policies of the Soviet government with massive sabotage of mobilization. As of January 1, 1920, more than 250 thousand peasants who deserted from the Red Army were registered in the Tambov province.

The epicenter of the uprising was the Tambov district. Here, on August 19-20, 1920, in the villages of Afanasyevka and Kamenka, detachments of “greens”, with the support of local residents, defeated food detachments. On March 21, a gathering was convened in Kamenka, at which local peasant G.N. Pluzhnikov, nicknamed Batko, proclaimed the beginning of an uprising against the communists and the surplus appropriation system. Thus a flame of protest broke out, quickly engulfing the neighboring volosts and then the counties in a fire.

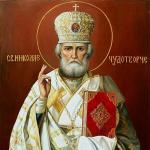

One of the leaders of the uprising, after whom it was later named, Alexander Stepanovich Antonov was born on July 26, 1889 in Moscow in the family of a reserve sergeant major, a Tambov tradesman, and a Moscow dressmaker. Since the early 1890s. he lived in the city of Kirsanov, Tambov province, where he studied at the city three-year school. Since 1908, he became an activist in the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) and the leader of one of the groups of independent socialist revolutionaries, which operated in the Kirsanovsky district. In the police materials, where he appeared under the nicknames Shurka, Rumyany, Antonov was characterized as an excellent conspirator and organizer, brave, daring and honest by nature. On February 20, 1909, in Saratov, while preparing an assassination attempt on General A.G. Sandetsky, he was arrested as part of a group betrayed by the famous provocateur Yevno Azef, and sentenced to death, commuted to lifelong hard labor. He was imprisoned in Tambov, Moscow and Vladimir. Tried to escape twice. Until 1916 he was kept in shackles. On March 3, 1917, Antonov was released under an amnesty and returned to Tambov, where on April 15, 1917 he began serving in the city police. He proved himself to be an excellent employee and at the end of October 1917 he was appointed to the post of chief of the Kirsanovsky district police. In his work he showed initiative and determination: he disarmed a train with Czechoslovak troops, prevented the destruction of former landowners' estates, and resolutely fought against moonshine. On February 6, 1918, Antonov was elected to the Kirsanovsky Council of Soldiers, Workers and Peasants' Deputies.

A. S. Antonov. 1920-1921

After the Bolsheviks defeated the Left Socialist Revolutionary rebellion in July 1918, Antonov, trying to avoid arrest, left his position and went underground. In December 1918, he created a fighting squad, which began a successful fight against the Bolsheviks, in particular with members of the food and security forces.

With the arrival of a detachment of 500 fighters led by Antonov in Kamenka on August 25, 1920, events went beyond the scope of a local rebellion. The first attempt by the provincial authorities to suppress the peasant uprising by force of arms was futile. By the end of summer, the entire Kamensk volost was in the hands of the rebels, and they began to move towards the provincial center - Tambov.

The rebels' campaign caused alarm among the local Bolshevik leadership: it became obvious that what was happening was much more serious than the peasant revolts of previous years. In the area of the uprising, detachments led by I.E. Ishin, E.I. Kazankov, and I.S. Matyukhin were active, and the fighting squad of A.S. Antonov occupied the large village of Ramza. By the beginning of the autumn of 1920, the provincial authorities realized that they would not be able to suppress the protests on their own. In Orel, where the headquarters of the military district was located, there were persistent requests from Tambov for the urgent dispatch of army units.

Since the emergence of the peasant movement, punitive measures began to be applied to the rebels. Thus, in the order of the operational headquarters of the Gubernia Chek of August 31, 1920, it was proposed to take hostages from 18 years of age, regardless of gender, primarily family members of the rebels and their sympathizers. The property of such Bolshevik opponents was to be confiscated and their houses demolished or burned. Residents of villages found participating in the protests were subject to emergency food indemnities, in case of non-fulfillment of which, confiscation of land and property was provided, as well as forced eviction: adults to concentration camps, children to orphanages.

The command staff of the Tambov Gubchek 1921

The ruthless policy of the Tambov authorities caused grumbling among commanders and ordinary Red Army soldiers. Some units refused to carry out the order to burn the villages, and the fighters went over to the side of the rebels. When the punitive forces approached, the population of entire villages left their homes and went into the forests, multiplying the number of rebels.

On September 10, 1920, Latvian Yu. Yu. Aplok took command of the Red Army troops on the territory of the province. Repressions against the rebels became even more brutal. In an address dated September 16, the commander stated that all “bandits” captured with weapons would be shot on the spot, and villages that resisted the troops would be burned to the ground. On September 18, the village was burned for the murder of two Red Army soldiers. Zolotovka, Kirsanovsky district.

With the beginning of the uprising, it became clear that the rebel troops were well armed and organized, and their military operations were well thought out. This became possible because the peasant movement was led by people who had remarkable organizational skills and had combat experience in both army service and participation in anti-government protests. Particularly noteworthy is Pyotr Mikhailovich Tokmakov, a peasant from the village. Monks of Kirsanovsky district, second lieutenant of the Russian Imperial Army, participant. An associate of Antonov in the fighting squad in the fall of 1920 - winter of 1921, he became one of the military leaders of the uprising, commander of the United Partisan Army of the Tambov Territory. Another bright personality was Ivan Egorovich Ishin, a peasant from the village. Kalugino, Kirsanovsky district, Socialist Revolutionary since 1905, since the fall of 1920, member of the provincial committee of the Union of Labor Peasants (STK) - the main ideologist of the uprising.

Most of the leaders of the insurrectionary movement considered themselves Socialist Revolutionaries, although the central organizations of the right and left Socialist Revolutionaries were not directly related to the course of the uprising. At the same time, the ideological influence of the Socialist Revolutionary Party is noticeable in the content of the program and charter of the STC. He considered his main task to be “overthrowing the power of the “communist-Bolsheviks” who brought the country to poverty, death and shame.” The program included such goals as “political equality of all citizens”, “convening a Constituent Assembly to implement a new political system, and before the start of its work - organizing power on an elective basis, but without the Bolsheviks”, “enforcing the law on the socialization of the land in full”, “satisfying the population of cities and villages with basic necessities, primarily food, through cooperatives”, “partial denationalization of factories and factories”. Thus, the program documents of the rebel movement were close to peasant interests, and the creation of more than 300 STC cells during the uprising indicates support for their activities from the rural population.

The rebel army, formed mainly from local peasants, enjoyed the support of rural residents. Good knowledge of the terrain allowed the rebels to carry out surprise attacks on food detachments or, by skillfully maneuvering, avoid military clashes with army units that outnumbered them. The tactics of guerrilla warfare significantly complicated the actions of the Bolsheviks, and the deliberate reduction in combat activity more than once created the illusion of victory among the Red commanders. This happened with Aplok, who, after several successful military operations, on October 3, 1920, issued a victorious order and reported to the center about the suppression of the rebellion. But this statement was premature. Antonov's detachment of 2 thousand soldiers retreated to the Balashov district of the Saratov province, and from there in several groups of 400 fighters secretly moved to a new area of operational operations near the Zherdevka - Borisoglebsk railway. Soon more than half of the Borisoglebsk district was under the control of the rebels. The leadership of the Tambov Provincial Committee of the RCP(b) again sounded the alarm, asking to send new army units. The rebels also took measures to coordinate the actions of their troops. November 14, 1920 in the village. Moiseevo-Alabushka, Borisoglebsk district, field commanders held a meeting at which they decided to create the United Partisan Army of the Tambov Territory and elect the Main Operational Headquarters of 5 people, headed by A. S. Antonov.

Antonov's armed forces combined the principles of the regular army (21 regiments in 3 armies, a separate brigade) with the actions of irregular formations. Along with recruiting volunteers from local residents, the rebels also resorted to forced mobilization. The majority of peasants, ordinary participants in the movement, were ready to act only within their volost, maximum county, without moving away from their native village. And in this regard, the “Antonovschina” was a typical peasant uprising with a completely predictable ending - military defeat upon leaving their homeland. But that will come later, but for now the rebels have quite successfully used all the advantages of guerrilla tactics of surprise attacks and rapid retreats.

Particular attention in the partisan army was paid to propaganda work in units and agitation among the local population. It was simplified in nature, expressed in the form of slogans “Down with the communists!”, “Long live the working peasantry!” and was based on criticism of the Bolshevik food policy, the “fruits” of which the peasants had already fully felt.

As the uprising spread, agitation became even more effective in form and targeted in character. From a survey of prisoners captured by the Reds in battle on January 8, 1921, it was established that “agitators are traveling around the villages... three or four people each, gathering for gatherings at which they mainly call for the destruction of the communists and the communist system because the communists they are taking away the last bread from the peasants and that they will have to die of hunger in the end, and they are calling on them to enroll in partisan detachments.” In their appeals, the rebels outlined their goal as the liberation of the people from the yoke of the communists.

Thus, the insurrectionary movement of Tambov peasants was basically a protest against the arbitrariness of the Communist Party, whose members were referred to by local residents as “rapists”, “robbers”, “bandits”. This hatred was the reason why the “committee members” were the first to be executed by the rebels. The peasants’ commitment to the traditional form of communal self-government was manifested in the fact that in practice the rebels mainly implemented the slogan “Soviets without communists!”, retaining executive committees after the arrests of members of the RCP (b) and re-election of village councils.

In January - February 1921, the uprising reached its climax: the influx of peasants into the rebel groups became maximum, and by February 1921 the number of Antonov troops was 40 thousand people. Throughout January there were fierce battles between partisans and Bolshevik troops. On January 23, 1921, the Antonovites captured the large village of Uvarovo, and in the evening of the same day the Tokarevka station came under their control. Despite the efforts of the regular units, the resistance of the rebels could not be broken. Moreover, desertion increased in the ranks of the Red Army in the province. In just two months (January and February) of 1921, 8,362 people deserted from the troops stationed in the province. The commander of the Tambov province troops, A.V. Pavlov, explained the lack of success by saying that in the region “it is not banditry, but a peasant uprising that has captured wide sections of the peasantry.”

In order to calm the popular protest, the Soviet leadership decided to abolish the surplus appropriation system: it was removed from the province more than a month before the well-known decision of the Tenth Congress of the RCP(b) in March 1921 to replace the surplus appropriation tax with a tax in kind. Realizing that this concession to the peasantry was not enough, the authorities intensified repression. By March 1, 1921, the troops of the Tambov province numbered 32.5 thousand bayonets and 7,948 sabers with 463 machine guns and 63 guns. In addition, they had at their disposal 8 aircraft, 4 armored trains, 7 armored vehicles and 6 armored cars.

In the spring of 1921, the final stage of the Tambov uprising began. A strong blow to the rebel army was dealt by a two-week voluntary surrender. During the period from March 21 to April 12, 1921, about 7 thousand partisans surrendered into the hands of the authorities. The beginning of field work played a role: not all peasants were ready to sacrifice the sowing season for the sake of fighting the “rapist communists.” But the leadership of the United Partisan Army of the Tambov Territory was not going to lay down their arms. On April 11, 1921, units of Antonov’s 2nd Army occupied the large factory village of Rasskazovo, located just 30 km from the provincial center, almost without a fight. The total number of armed rebels, according to the military intelligence of the Red Army on May 1, 1921, was approximately 21 thousand people.

The defeat of the protest movement began with the appointment of M. N. Tukhachevsky to the post of commander of the troops of the Tambov province. I. P. Uborevich became his deputy, and N. E. Kakurin became his chief of staff. To control the military, G. G. Yagoda (Yehuda), a member of the Presidium of the Cheka, was sent to the province through the special services.

Famous Soviet military leaders, future marshals G.K. Zhukov and B.M. Shaposhnikov took part in the suppression of the peasant uprising. The author of the idea to use armored squads against the rebel cavalry was the commander of the 1st combat section, I. F. Fedko. The cavalrymen of G.I. Kotovsky’s brigade were remembered by local residents for their robberies and looting.

G. I. Kotovsky. 1920s

Arriving in Tambov on May 12, 1921, Tukhachevsky immediately conducted the matter decisively in a military manner. The territory covered by the uprising was divided into sectors that were subject to systematic occupation. To intimidate the population, the famous order No. 130 was issued, and in its development, the authorized commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, headed by V. A. Antonov-Ovseenko, approved order No. 171 on June 11, 1921. According to these draconian measures, the administration of local political commissions and rural revolutionary committees, rebel farms were destroyed and houses were destroyed, partisan family members were taken hostage and sent to concentration camps. In June 1921, at an army party conference, the commander reported that “5,194 single hostages and 1,895 families were taken.” They did not spare anyone, not even children. According to the head of the provincial department of forced labor, V.G. Belugin, dated June 22, 1921, “a large number of children, even infants, are entering the camps.” In 10 concentration camps of the Tambov province, according to data on August 1, 1921, 1,155 children were kept, of which 397 were under 3 years old, 758 were under 5 children.

In a number of villages, punitive troops resorted to shooting hostages. Archival documents confirm this. Thus, at a meeting of the Kirsanovsky district political commission on July 10, 1921, the chairman of the authorized “five” reported that in the village. On June 3, 58 people were taken hostage in Bogoslovka. The next day the first batch of 21 people was shot, and on July 5 - 15 people. Speaking at a meeting of representatives of the political commission and volost revolutionary committees on July 5, 1921 on the implementation of order No. 130 in the Lazovsky district (most likely, the document refers to the Bolshe-Lazovsky volost of the Tambov district. - Ed.), Comrade Machikhin complained: “Nothing happens without executions. Executions in one village have no effect on others until the same measure is carried out in them.”

Order of the commander of the troops M.N. Tukhachevsky on the use of chemical weapons against the rebels 06/12/1921

Another example of barbaric counterinsurgency methods was Order No. 116 of June 12, 1921, on the use of poison gases. The use of chemical weapons was documented during the artillery shelling of the “island north-west of the village” carried out on August 2, 1921. Kipets of the Karai-Saltykovsky volost,” as a result of which 59 chemical shells were fired.

In the summer of 1921, Antonov's main forces were defeated. At the beginning of July, the leader of the rebels issued an order asking the combat troops to split into groups and hide in the forests or go home. The uprising broke up into a number of pockets, which the Bolsheviks liquidated by the end of the year. Alexander Antonov and his brother Dmitry, who also took part in the anti-communist protest, were killed on June 24, 1922 in the village. Nizhny Shibray, Borisoglebsk district, during a security operation.

According to the reports of the leaders of the suppression of the uprising, from September 1920 to August 1921, about 12 thousand rebels were killed in battles, in addition, up to 1.5 thousand partisans and hostages were shot. The overall demographic losses are even higher: the population of those areas of the province where residents took the most active part in the insurgent movement decreased by 82 thousand people by 1926. It is more difficult to assess the moral damage that the Tambov village suffered as a result of the harsh suppression of mass discontent among the peasants by the communist authorities.

Vladimir Bezgin, Doctor of Historical Sciences

Tambov uprising (1920-1921)

"Antonovschina"

Peter Aleshkin

© Peter Aleshkin, 2016

ISBN 978-5-4483-4446-6

Created in the intellectual publishing system Ridero

Introduction

The peasant movement in the Tambov province in the early 1920s, better known as the “Antonovschina,” was a significant event in the entire post-October history of Russia, and with its scale, political resonance and consequences was an event of all-Russian significance. A powerful social explosion forced the state authorities to urgently search for fundamentally new ways out of the deep social crisis in which the country found itself.

Studying the experience of the peasant movement in the Tambov province is relevant in today's Russia, when a radical transformation of the system of power is taking place, as a result of which tense conflicts appear in the state, protest phenomena arise, sometimes turning into armed ones. A careful analysis of conflicts, despite different ideological approaches, reveals something in common, both in the reasons for their occurrence (one of the main reasons is the ill-considered policies of the authorities), and in their development, in the methods of resolving them, including the use of military methods. Analysis and taking into account the experience of socio-political protest in the Tambov region of the 1920s will help to avoid mistakes.

Currently, there is an opportunity to take an objective look at the reasons, factors, dynamics of the peasant movement in the Tambov province, which, as proven by numerous researchers of the civil war and the first years of the formation of Soviet power, significantly influenced the policy of the Soviet government, forced it to abandon the policy of war communism and move to a new economic policy. The history of Antonovism cannot be fully understood within its own chronological boundaries, without a broader historical context.

In the development of Soviet historiography on the topic under study, several stages can be distinguished. The first stage began immediately after the events in question and continued until the early 1930s. The study took place in hot pursuit. The problem was covered mainly within the framework of the history of the Civil War as a whole. Many authors were direct participants in those events1.

M. N. Tukhachevsky left a work that summarized the experience of the Red Army’s struggle with the peasant uprising. The author saw the deep roots of the peasant struggle, assessing “Tambov banditry” as a peasant uprising caused by food policy. He saw in the leader of the movement a gifted organizer and commander. According to the author, the fight had to be waged mainly not against bandits, but against the entire local population, and these were not battles and operations, but a whole war. Tukhachevsky understood that it was possible to cope with the popular movement, which in every possible way helped its partisan detachments and had an unfriendly attitude towards the Red Army, not by destroying the “gangs”, but by restoring the trust of the people, the new Sovietization of the countryside and a change in economic policy. “Without our actual implementation of the new economic policy on the ground, without attracting the peasantry to the side of the Soviet government, we would never have been able to completely eliminate the uprisings. This is the basis of the struggle,” he admitted. The peasant insurrectionary movement “cannot be completely eliminated if the working class fails to come to an agreement with the peasantry, if it fails to direct the peasantry so that the interests of the peasantry are not violated by the socialist construction of the state.”2

The 1920s were characterized by the absence of a general methodological approach; a large number of sources were introduced into circulation, often without any critical analysis. There were different points of view about the nature of peasant uprisings and peasant protest against Soviet power. At the same time, different terms were used in the literature - “peasant uprisings”, “insurgent movements”, “kulak uprisings”, etc. In particular, M. N. Pokrovsky wrote about this: “in 1921, the center of the RSFSR was covered by an almost continuous ring of peasant uprisings "3 The authors spoke of peasant uprisings as a new round of civil war between former allies - the proletariat and the peasantry.4

Some aspects of the history of peasant protest against Soviet power received quite detailed coverage during this period. A large number of works, many of which were written by participants in the events in question, were devoted to military action against the rebels. During this period, value judgments appear about the social composition, level of organization and mass scale of performances. Forms of peasant protest were often considered in the context of more general problems. The works contained a lot of factual material, with the help of which it was not difficult to destroy the myth about the Socialist-Revolutionary-Gangster nature of Antonovism. Subsequently, many of the interpretations and conclusions that appeared at this time were rejected by Soviet historical science.

In the 1920s, the history of the peasant movement was covered in emigrant literature. The works of emigrant researchers are characterized by a different vision of the events of the civil war from the Soviet one, a different methodological basis, interpretations and a set of historical sources used. Researchers in emigration were limited in their ability to use documentary material: mainly based on memories and what was taken out of the country, materials from Soviet literature. Many works were prepared by direct eyewitnesses of the events of the Civil War - emigrants of the first wave. The authors interpreted the events in Soviet Russia from anti-communist, anti-Soviet positions.5 Emigrant researchers were within a less rigid ideological framework. Most of them, however, could not look at the events of the civil war impartially.

At the second stage of development of Soviet historiography of the topic, which covers the 1930s - the first half of the 1950s, there is a unification of assessments, both in relation to the civil war as a whole, and in relation to the relationship between the state and the peasantry. Following the guidelines of the short course “History of the CPSU (b)” predetermined the initial standard for the work of researchers.6

The peasantry was seen as an object of party policy in the countryside. It was in the 1930s that the designation of peasant uprisings as “kulak uprisings” was firmly established in literature. Their emergence was associated with the activities of counter-revolutionary organizations, Socialist Revolutionary and Menshevik parties, imperialist intelligence services and church leaders. Peasant uprisings in the territory controlled by the Soviet government were called kulak, and in the territory of the “whites” - actually peasant uprisings and partisan movements.

The third stage of Soviet historiography covers the second half of the 1950s - the mid-1980s. The result of the “thaw” in the history of Soviet society, which began in the second half of the 1950s, was that historians were able to develop many problems that had not received coverage in previous decades.7 Researchers from the 1960s to 1980s continued to interpret peasant uprisings as “ kulak", paid increased attention to the role of various opposition parties and forces in them - Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, former officers. The participation of the broad peasant masses in the uprisings was interpreted as “the hesitation of the middle peasants.”

Since the second half of the 1980s, under the influence of political processes in the USSR, a new trend has emerged in the study of the history of the peasantry during the revolution and civil war. Due to increased access to archival materials and the end of the monopoly position of Marxist-Leninist ideology in the interpretation of history, researchers were able to begin a broader study of the problems of the history of the peasantry during the Civil War.8

Tambov researchers S.A. Yesikov and V.V. Kanishchev, studying the activities of the Soviets of the Working Peasantry, came to the conclusion that the STC of all levels, no matter how good intentions they were guided by, remained primarily organs of uprising. Although the STC program outlined an early end to the civil war, there were absolutely no concrete steps towards achieving civil peace in the documents and practical activities of the Union organization. Like the Soviet government, the embryonic bodies of independent peasant power in the Tambov province were aimed at a merciless fight against their political opponents. The authors believe that the STC did not become a mass people's organization, but only emergency bodies for the leadership of the rebel movement. The role of the Unions of the Working Peasantry in giving the traditionally rebellious peasant unrest a certain organization and awareness and reflecting the search for a peasant alternative to the dictatorship of the proletariat at the time of its crisis. Conventionally, they called this alternative “Antonov NEP.”

In 2005, the Tambov Vendee exhibition was opened at the Tambov Regional Museum of Local Lore. It is dedicated to one of the most tragic pages in regional and Russian history - the peasant war in the Tambov region of 1920-1921, when the new government and peaceful farmers, driven to despair by the thoughtless and cruel food policy of the Soviet state, collided in a fierce confrontation. The authors of the exhibition raised the problem of an objective assessment of historical events. According to their plan, it is necessary to “rise above the fray”, not to blame either side, to show that in a civil war there are no winners, that bitterness at the time of the Tambov peasant uprising reached an extreme degree, and blood flowed like a river. The exhibition features about two hundred exhibits. These are unique documents, photographs, personal belongings of event participants from the funds of the Tambov Regional Museum of Local Lore, the FSB archive for the Tambov Region, and the State Archive of the Tambov Region. Most of the materials are being exhibited for the first time.

The exhibition was met with caution. After all, for decades our compatriots were captive of a great historical untruth. Official Soviet historical science viewed the “Antonovism” as a kulak-SR bandit rebellion that “took the form of political banditry with a semi-criminal overtone.” The organizers of the exhibition were asked to rearrange the emphasis and “show more atrocities of the bandits.” Based on the concept of the exhibition, the authors sought to present a significant array of documents of two opposing sides, diverse in type and thematic composition: orders, reports, leaflets, appeals. The principle of objectivity required evidence of the cruelty of the hostile parties. However, in complete contradiction with the still prevailing unambiguous opinion formed from the standpoint of Soviet historiography, documentary evidence of the atrocities of Antonov’s army could not be found. There were no villages and villages burned by the rebels, there were no hostages and reprisals against the civilian population. Discipline in Antonov’s army was regulated by the “Temporary Regulations for Punishments Judgable by Army Courts,” according to which even “rough treatment of prisoners” was severely punished. The partisans were ruthless and merciless towards the “stony” communists - they executed captured commissars, red commanders, and leaders of food detachments. Ordinary Red Army soldiers, after political conversations about the goals and causes of the “nationwide uprising against communist rapists,” were offered to join the ranks of the rebels; if they refused, they were given a “leave” - a document with which they freely returned to their unit or home.

However, so far in Russia, including in the Tambov region, where the most powerful anti-communist uprising of peasants took place in 1920-1921, they do not know, moreover, they do not want to know anything that could shake the usual position of an extremely negative attitude towards the leader of the uprising, Alexander Stepanovich Antonov and the movement that he led.

Here is just one eloquent example. In the ancient wealthy village of Parevka, Kirsanovsky district, in June 1921, in execution of order No. 171 of the Plenipotentiary Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, hostages were captured and shot. According to some sources, 86 women, old people and children, according to others - 126. In the local school museum you can see photographs of security officers, village councilors - “those who established Soviet power in the Tambov region.” The famous film director Andrei Smirnov visited the museum during the filming of the feature film “Once Upon a Time There Was a Woman,” he asked the teacher who showed him the exhibition: “Where is the memory of those fellow villagers of yours who were shot in 1921?” In response I heard: “Well, we were taught that these were bandits.”

The history of the Tambov uprising is still perceived very sharply, very painfully. People have very little knowledge about this period of our history, and what knowledge they have was obtained at a time when the peasant uprising was considered banditry. This is very sad, because the leaders of the uprising, the ordinary soldiers of the rebel army, and the entire unconquered Tambov peasantry deserve special memory.

“This was the last peasant war in Russia,” Alexander Isaevich Solzhenitsyn wrote about them, “but the Tambov persistent uprising showed that the Russian peasantry did not give up without a fight.” Through the efforts of the great writer, “Antonovism” gained international fame. In the 1990s, during the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Vendée uprising in France, he was the first to draw the attention of the world community to the similarity of the uprisings of French and Tambov peasants who opposed the sharp invasion of the revolutionary regimes into the interests of the rural population. This is where the expression “Tambov Vendee” came from.

The command staff of the Tambov Gubchek. 1921

The roots of the Tambov uprising go back to the beginning of the 20th century. Then the Tambov province became one of the main areas of the powerful peasant movement against the landowners; the protests were especially strong in the Tambov, Borisoglebsk, and Kirsanov districts. Tambov Governor V.F. von der Launitz and his closest subordinates acted as decisive pacifiers of the peasant uprisings in 1905. It is no coincidence that the local organization of Socialist Revolutionaries directed its terrorist activities against them, among the organizers of which were the future leaders of the party - V. Chernov, M. Spiridonova and others. Socialist Revolutionary slogans were popular here, which became the political expression of peasant demands. It was then that the activities of the future leader of the uprising, Alexander Stepanovich Antonov, began; he “considered himself a Socialist Revolutionary of 1905” and was formed as a romantic revolutionary. As a member of the Tambov group of independent socialist revolutionaries, he took part in “exes” for the needs of his party. Let’s make a reservation that the “ex” of “Rumyanoy” or “Osinovy” (as Antonov was referred to in the police orientation) were bloodless. Yet in 1910 he was accused of “injuring” a gendarmerie officer and sentenced to death by hanging. His case was put on the table of the Minister of Internal Affairs P.A. Stolypin, who revised the sentence and replaced capital punishment with “hard labor without term.” Antonov served hard labor in the Vladimir Central Prison.

The events of 1917 and the February Revolution took place in the Tambov region under the sign of Socialist Revolutionary agitation. Elections to the Constituent Assembly showed that 76% of voters in the Tambov province voted for representatives of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. The Social Revolutionaries led a new rise of the peasant revolution in the Tambov region. They were the first in Russia to direct the struggle of peasants for landowners' lands into a peaceful channel. The famous “Order No. 3” of the Tambov Socialist Revolutionary Provincial Land Committee transferred noble estates to the control of peasant land committees and saved their economic and cultural values from pogroms. This document was issued a month earlier than the Decree on Land, which finally transferred the land of the landowners into the hands of the peasants.

The Tambov province has always been a grain province: on the eve of 1917, it produced more than 60 million pounds of agricultural products. She fed herself, fed Russia, and supplied another 26 million poods to the European market.

The main reason for the clash between the Tambov peasants and the new “worker-peasant” government was the circumstances of the Civil War, due to which the province turned out to be one of the main food bases of the country. The “military-communist” policy in the countryside immediately boiled down to the confiscation from the peasants of food necessary to provide for the army and the urban population. Mobilizations for military service and various types of duties (labor, horse-drawn, etc.) further intensified the confrontation between the peasantry and the authorities. In 1918, about 40 thousand peasants took part in the uprisings against violence by the emergency authorities of the Soviet government. The suppression of uprisings was carried out using military force and executions. It was during this period that Marina Tsvetaeva went on a “difficult, humiliating, risky” trip to the Usman district of the Tambov province to buy food for her daughters Ali and Irina, who were dying of hunger in Moscow. What she saw and experienced shocked the poetess and spilled out into tragic lines:

“Harness the blood horses to the logs!

Drink the count's wines from puddles!

Monarchs of bayonets and souls!

Sell - by weight - chapels,

Monasteries are auctioned and scrapped.

Ride your horse to God's house!

Drink up the bloody drink!

Stables - to cathedrals! Cathedrals - in the stalls!

In the devil's dozen - calendar!

We are under the rug for saying: Tsar!”

By the beginning of 1919, 50 food detachments from Petrograd, Moscow and other cities with a total number of up to 5 thousand people were operating in the Tambov province - no other province knew such a scale of confiscations. The peasants were outraged by the arbitrariness in determining the volume of supplies, the abuse of brute force, and the neglect of the storage and use of products confiscated from them: the bread taken from the allotment rotted at the nearest stations, was drunk by food detachments, and distilled into moonshine.

The situation in the village became especially tragic in 1920, when the Tambov region was struck by drought. By the end of the year, the peasants of the three most grain-producing districts - Kirsanovsky, Tambov and Borisoglebsky - were starving, “they ate not only chaff and quinoa, but also bark and nettles,” and there was no grain left for spring sowing. The incredible volume of surplus appropriation of 11.5 million poods meant death from starvation for the peasantry.

Confiscation act: “Property was confiscated from the families of bandits... a worn corset - 1, a child’s dress - 1, a children’s sweatshirt - 1...”

How did the surplus appropriation go? The methods of the soldiers were inhuman and reminiscent of the Middle Ages - floggings, beatings, violence, executions. The commander of the food detachment, citizen Margolin, upon arrival in the village or volost, assembled a gathering, herded the peasants to the central square and solemnly declared: “I brought death to you, scoundrels. Look, each of my soldiers has a hundred and twenty lead deaths for you scoundrels.” This was followed by “foraging”, when, as documents show, “neither sheep nor chicken” were left behind. The men were flogged, put in a cold barn, lowered into a well in the cold, their beards were set on fire, etc. The settlement was burned. The commander of the 1st Cavalry Regiment N. Perevedentsev received the nickname “Burnt” from the local population, because “to consolidate the victory and punish the rebels for their tenacity in battle,” he burned them to the ground. Tambov villages. People had only one thing to do: proactively collect their property, take a sawn-off shotgun and go into the forest. This is how Antonov’s army was replenished.

Alexander Stepanovich Antonov himself was released under an amnesty on March 4, 1917. Returning from the tsarist penal servitude, he first worked in the Tambov police, then headed the Kirsanov district police, where he enjoyed great authority. But the violence that was happening towards the peasantry forced Antonov to break up with the new government. He left the post of chief of the Kirsanov police, with a small detachment of 150 people went into the Kirsanov forests and acted exclusively against food detachments.

Local authorities, first Kirsanov's, then provincial, tried to discredit Antonov. Publications appeared, even proclamations and leaflets, where he was compared with the famous local criminal Kolka Berbeshkin. Antonov tracked down Berbeshkin's gang and destroyed it. He informed the Kirsanov and provincial authorities that the gang had been destroyed, and indicated the place where the killed bandits were buried. “In terms of the fight against the criminal element, I am ready to provide assistance to the new Soviet government, but for ideological reasons I completely disagree with you, because you, the Bolsheviks, brought the country to death, poverty and shame.”

The Peasants' War of 1920-1921 grew out of an insurgency that began in the fall of 1918. In the following months, there were outbreaks of revolts in individual villages, and combat groups and partisan detachments appeared in forest areas. “Fighting squad” A.S. Antonova became the core of the rebel army.

A small uprising that broke out in mid-August 1920 in the villages of Khitrovo and Kamenka, Tambov district, where peasants refused to hand over grain and disarmed the food detachment, under the organizing influence of the Antonov squad, quickly spread throughout the central and southeastern part of the province. However, the Tambov authorities continued to receive orders from the Center to send grain trains to Moscow, which caused growing discontent among the peasants.

The rebels formed a “peasant republic” on the territory of Kirsanovsky, Borisoglebsky, Tambov districts with a center in the village. Kamenka. Armed Forces A.S. Antonov combined the principles of building a regular army with partisan detachments and attracting the population for reconnaissance, transportation, etc. A network of political agencies operated in the partisan army. The organization and leadership style of the Antonovites turned out to be sufficient to conduct successful military operations of the partisan type with the skillful use of natural shelters, close communication with the population and its full support, and the absence of the need for deep rear areas, convoys, etc. The goals of the rebels were specific, the results of military operations increased the morale of the army and attracted new forces to it. On the battle banners of the rebels was inscribed the famous Socialist Revolutionary slogan: “In the fight you will find your right!” The influence of the Social Revolutionaries on the ideology and organization of the insurgent movement is undeniable. It was especially noticeable in the activities of the Union of Working Peasants, whose main task was the overthrow of the “commissar state”. The STC committees, there were about 300 of them, performed the functions of local civil authorities in the territory covered by the uprising.

By the beginning of 1920, Antonov became the head of the General Staff of the rebel army, which numbered up to 40 thousand people (taking into account partisan methods of warfare - up to 200 thousand people). He was elected by secret ballot on an alternative basis from five candidates. To lead the peasant insurgent movement, special people were required, capable of leading a spontaneous, organizationally loose mass movement without much chance of success, psychologically ready for self-sacrifice in the revolution, close to the peasant environment, and with experience in revolutionary activity. The main leaders of the Tambov uprising of 1920-1921 were endowed with these features: A.S. Antonov, I.E. Ishin, G.N. Pluzhnikov. The outstanding personal qualities of Alexander Stepanovich Antonov were also recognized by the high command of the Red Army: “Antonov is a remarkable figure with great organizational abilities, an energetic, experienced partisan,” “Antonov is not a criminal bandit, as he was portrayed in our press, but an old Social Revolutionary underground member, an active participant agrarian movement in the Tambov province during the first Russian revolution of 1905-1907, former political prisoner.”

Initially, the Tambov leadership allocated no more than three to four weeks to liquidate the peasant uprising. But the guerrilla method of warfare of the rebels made it difficult for the Soviet troops to operate. By the end of December 1920, it became obvious that it was impossible to cope with the rebel forces available, although over 10 thousand bayonets and sabers acted against the rebels.

Soviet historiography was silent about the question of A.S.’s attitude. Antonov and the entire rebel movement towards Orthodoxy. It was no coincidence that Solzhenitsyn called the Antonov movement the Tambov Vendée. After all, the uprising of French peasants had a religious overtones. “May Almighty God help us defeat the enemy and establish a government that would rule us for the benefit of the now weeping and oppressed people...” - these words from the leaflet of the Main Headquarters of the partisan army testify to the deep religious feeling of the rebels. The appeal to the Red Army soldiers, in which the leader of the uprising calls on them to take the side of the rebels and calls them to march on Moscow, ends with the words: “God is with us!” In poems attributed to A.S. Antonov, the word Vera is written everywhere with a capital letter: “For Faith, Motherland and Truth, for Faith, Freedom and Truth!”

At the beginning of 1921, the central government took decisive action against the rebel army. The highest body in the fight against “Antonovism” at the end of February - beginning of March 1921 became the Plenipotentiary Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, headed by V.A. Antonov-Ovseenko. She concentrated all power in the Tambov province in her hands. In February, a change in the general policy of the state towards the peasantry was announced - the surplus appropriation system was replaced by a tax in kind. The men cried with joy, even those who were in the rebel detachments, and said: “We won.” To this Antonov told them: “Yes, men, you won, although this victory is temporary. And we, gentlemen commanders, are finished.”

Large combat-ready, technically equipped military contingents numbering 110 thousand bayonets and sabers, 4 mobile cavalry brigades, 2 air detachments, an armored detachment, 6 armored battalions, 4 armored trains and an airborne detachment were sent to the Tambov region. A clear structure of military administration was created, the province was divided into 6 combat areas with field headquarters and emergency authorities - political commissions.

In April 1921, a decision was made “On the liquidation of Antonov’s gangs in the Tambov province,” by which M.N. Tukhachevsky was appointed “sole commander of the troops in the Tambov district.” The strategy consisted of a complete and brutal military occupation of rebel areas. The essence of this strategy is set out in the “Instructions for Combating Banditry”, order No. 130 of Tukhachevsky of May 12 and order No. 171 of the Plenipotentiary Commission of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of June 11, 1921. All villages of the Tambov province were divided into Soviet, neutral, bandit and malicious bandit. In relation to the “bandits” and “maliciously bandits”, an occupation regime was introduced. Troops entered the village. The population remaining in the village was herded to the central square, hostages were taken, and they were given two hours. If the men did not come out of the forest with weapons, the hostages were shot. Disobedience and concealment of “bandits” and weapons also resulted in execution. Then there was confiscation of property, destruction of houses and deportation of families of participants in the rebellion to remote provinces of Russia. The orders were carried out “severely and mercilessly.” On July 12, 1921, the commander of the provincial troops, M. Tukhachevsky, signed order No. 0116 on the use of chemical weapons against “bandits.” Concentration camps were established in the province. According to available data, there were 12 permanent concentration camps in the Tambov region. The largest - Tregulyaevsky - was located in the ancient, especially revered St. John the Baptist Monastery. There were also temporary detention camps: a square in a populated area (in Tambov it was Cathedral Square) was fenced off with carts and old people, women and children were kept in an open place under the sun. In the report “On the activities of the Provincial Directorate of Forced Labor” we read: “A large number of children, including infants, are admitted to the camps.” There was starvation in the concentration camps, the incidence of illness was extremely high, and “child hostages” over three years old were kept separately from their mothers.

Terror, repression, the most severe measures of suppression, and the military superiority of the “Reds” predetermined the defeat of the uprising. In the summer of 1921, Antonov's main forces were defeated. At the end of June - beginning of July, he issued the last order, according to which the combat detachments were asked to divide into groups and hide in the forests or go home. The uprising broke up into a number of small, isolated pockets, which were eliminated by the end of the year.

After the defeat of the uprising A.S. Antonov did not disappear from the province. He probably did not give up hope for the revival of the movement. Together with his brother Dmitry, he hid for another year in the Kirsanov and Tambov forests. By that time, his two sisters Valentina and Anna had already been arrested. Their fate is unknown; they disappeared somewhere in the basements of Gubchek.

A. Antonov's common-law wife, Natalya Katasonova, became one of the first prisoners of the Solovetsky special purpose camp.

Death overtook the Antonov brothers not far from their homes. They took their last battle on June 24, 1922 in the village of Nizhny Shibray, Borisoglebsk district. The Antonovs were killed during an operation developed by the anti-banditry department of the Tambov gubchek. Alexander was 33 years old, Dmitry was 28 years old. Their bodies were brought to Tambov, to the former Kazan Mother of God Monastery, where the Tambov provincial “Cherekvychaika” was located, and put on display for three days in order to show that the Antonovs no longer existed, and the uprising was finally suppressed. They were buried somewhere on the banks of the Tsna River. There are different evidence about the burial place, but so far no one is studying this issue. Even the memorial sign at the site of the foundation stone, where it was supposed to erect a monument to the leader of the last peasant war in Russia, Alexander Stepanovich Antonov, periodically disappears. In December 2010, he disappeared again.

The consequences of the terrible events of 1920-1921 are catastrophic. The Tambov province was liquidated as an administrative unit. The number of killed, shot, deported rebels and members of their families, ninety years later, has not been named. I think we are talking about several hundred thousand. Persecution for belonging to the Antonov movement continued for many years. They flared up with renewed vigor in the 1930s, when the tormented Tambov peasantry resisted collectivization. The salt of the Russian land, the guardians of Orthodox traditions and the national way of life, the great workers - the cultivators, the breadwinners of the country - were destroyed. This fact has not been recognized at the official state level. The archives are still not fully open. But the worst thing is oblivion and lies: the Tambov rebels on this long-suffering land are routinely called bandits.

Order of the commander of the troops M.N. Tukhachevsky on the use of chemical weapons against rebels*

G.A. Abramova, chief researcher of the Tambov Regional Museum of Local Lore

(photo materials courtesy of Galina Abramova)

-----------------

* The signature on the document was stained after Tukhachevsky himself was convicted as “the head of an extensive military-fascist conspiracy in the Red Army” and executed in 1937.

The peasant war in the Tambov province in 1920 - 1921, better known as the "Antonovschina", - the largest fact in the entire post-October history of the Tambov region - with its scale, political resonance and consequences, was an event of enormous all-Russian significance.

The peasant war in the Tambov province in 1920 - 1921, better known as the "Antonovschina", - the largest fact in the entire post-October history of the Tambov region - with its scale, political resonance and consequences, was an event of enormous all-Russian significance. A powerful social explosion forced the state authorities to urgently search for fundamentally new ways out of the deep social crisis in which the country found itself.

The interpretation of Antonovism as an anti-Soviet kulak-SR rebellion was far from historical truth and, due to its inferiority, inevitably gave rise to questions that it could not answer convincingly and consistently. Why did the movement, defined as “political banditry,” become so widespread and lead to a radical change in the entire policy in the village? If “war communism” has outlived its usefulness, then weren’t the Tambov men right in the historical sense who criticized it with weapons?

A vast, populous region (about 4 million people lived on an area of about 55 thousand square kilometers), with fertile land and grain abundance, has always been a source of human and material resources. Due to the circumstances of the civil war, the Tambov region became one of the main food bases of the republic. Proximity to the Center and relative distance from the main fronts favored the movement of food supplies here, and with them the whole complex of acute problems in relations between the peasantry and the state.

The Tambov province was a “grain province” and therefore experienced the full brunt of the food dictatorship and the “crusade” for bread. Already by October 1918, 50 food detachments from Petrograd, Moscow, Cherepovets and other cities with a total number of up to 5 thousand people were operating in the province - no other province had known such a scale of confiscations. Up to 40 thousand people then took part in the peasant uprisings against violence on the part of food detachments and poor committees.

In the Tambov province there was no shortage of combustible material for a social explosion. Here, as throughout Russia, war and revolution produced profound changes in the structure and psychology of society. The masses of people, knocked out of their usual social existence, but who had internalized the psychology of the “man with a gun,” represented a breeding ground for all kinds of discontent. It is worth considering that almost half of the men from the Tambov village served in the army and returned home not only with the determination to act in their own way, but also with weapons. It is not surprising that in the Tambov forests already in 1918 - 1919. There were many “greens” and “deserters” hiding, evading military mobilization. In June 1918, even Tambov and Kozlov for a short time found themselves at the mercy of the rebellious mobilized. In December, the provincial executive committee telegraphed to Moscow that “there is a widespread movement of peasants in the province” and that “the situation is very serious.” Local authorities insisted on assistance from the Center with military forces and leadership. As a result, by the end of 1918, about 12 million poods of grain were harvested from the 35 million poods of the “assignment”.

The motives for discontent were not limited to surplus appropriation or the arbitrariness of provincial “Robespierres.” The first experiments in organizing socialist agriculture date back to the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919. Attempts to induce peasants to switch to communal cultivation of the land even then often resulted in forced collectivization, which caused uprisings. However, the main problem in the relationship between the Soviet government and the peasantry remained bread, the food dictatorship.

The suppression of peasant uprisings was carried out with all determination from the very beginning, not stopping at the use of military force and executions. The justification for the harsh uncompromisingness and even cruelty was the real threat of starvation for millions of people and the conditions of the beginning of the civil war, on the fronts of which the fate of the revolution was being decided. Accordingly, Bolshevik ideology defined the meaning of the struggle for bread as a struggle for socialism, interpreted peasant protests against the forced seizure of grain as “kulak”, and attempts at armed resistance as “banditry”. All this terminology became firmly established in the official language and all Soviet documentation of 1918 - 1922.

The military nature of Soviet policy of that period was manifested not only in the fact that it was a wartime policy, but also in the fact that its implementation was based on the use of military force. In fact, surplus appropriation was carried out by the food army, which was subordinate to the People's Commissariat for Food, but organized and operating on the principles of a regular army. Accordingly, the resistance of the village ultimately took the form of armed uprisings. Peasant uprisings, as is known, were the general background of the era of “war communism”.

Of course, the first and most widespread form of resistance to surplus appropriation was the sharp reduction by the peasant of his farm. If in 1918 in Tambov province. per farm there was an average of 4.3 dessiatines of crops, then in 1920 - only 2.8 dessiatines. Even those peasants who were ready to put up with surplus appropriation as a temporary and forced measure could not help but be outraged by the arbitrariness in determining the volume of supplies, abuse of brute force and disregard for the storage and use of products confiscated from them - the results of their hard work. After their bread was raked clean, it often disappeared on the spot: it rotted at nearby stations, was drunk by food detachments, and distilled into moonshine.

The situation of the village became truly tragic in 1920, when the Tambov region was struck by drought. A 12-pound harvest even without surplus appropriation put the peasant in a hopeless situation, meanwhile the provincial appropriation remained extremely high - 11.5 million poods.

It is wrong to think that the local leadership, party and Soviet, was not aware of the seriousness of the situation. 06 this was stated quite openly at various conferences, meetings, and in information to the Center. Thus, according to the chairman of the provincial executive committee A.G. Shlikhter, there was an idea that for the food industry in the Soviet Republic everything is possible, therefore the reputation of the provincial food committee is comparable to the reputation of the provincial checker.

Against the backdrop of the disasters that befell the peasants and are increasingly associated with surplus appropriation, various political and ideological factors of the social explosion in the Tambov village recede into the background. Still, we should dwell on the role of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. The leaders of the fight against Antonovism largely attributed the scope of the movement to her influence and leadership. This thesis penetrated into historiography and dominated it for a long time, removing responsibility for what happened from the ruling party and shifting it to the opposition - which provided a formal reason for the final elimination of the AKP from the political scene and the complete elimination of the remnants of a multi-party system in the country. During the trial of members of the Central Committee of the AKP in 1922, among other things, they were accused of organizing the Antonov rebellion. It boiled down to the following points: firstly, the Social Revolutionaries participated in the preparation of the rebellion, creating the “Unions of the Laboring Peasantry”; secondly, the slogans of the rebels were nothing more than an illiterate presentation of ordinary Socialist Revolutionary slogans; thirdly, the movement started by the Socialist-Revolutionaries was abandoned by them to the mercy of fate and given into the hands of “the first rogue they came across” (i.e. Antonov). The awkwardness of such a charge is obvious, but in 1922 it played a role in the most severe sentence imposed on the leadership of the AKP, although the Supreme Revolutionary Tribunal admitted that the party did not officially take the lead of the movement. The set of documents in this collection, many of which come from the Socialist Revolutionary party environment and are published for the first time, helps to understand this confusing issue.

As is known, the Tambov region has been one of the bases of Socialist Revolutionary influence since the first Russian revolution. The names of V. Chernov, S. Sletov, M. Spiridonova are associated with her. Having taken deep roots in the Tambov village, the Social Revolutionaries, at the very beginning of the century, created “peasant brotherhoods” here, launched a “sentence movement” for land, and had a network of organizations. In the elections to the All-Russian Constituent Assembly in November 1917, the Socialist Revolutionaries won a complete victory in the province, collecting 71.2% of all votes (even higher in the countryside) and receiving 13 deputy mandates out of 16. One should not be surprised at the popularity of Socialist Revolutionary slogans in the insurgent movement, at least and because they were a political expression of purely peasant demands and did not contain anything unacceptable to the peasants.

After the expulsion of the Socialist Revolutionaries from the Soviets in 1918, and then the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, the most influential in the Tambov province. the political force has practically lost the main lever of its activities. For some time they maintained illusions about the possibility of legal work among the masses, mainly through cooperation and trade unions. But these hopes were not justified. “The S.-R.,” noted the report of the Provincial Committee of the AKP in 1920, “is being persecuted strictly.” Driven underground, the Socialist Revolutionaries inevitably faced the need to revive and intensify illegal activities. “Peasant brotherhoods” began to be recreated - by the end of the summer of 1920, there were about a dozen of them in only three districts of the Tambov province. At the same time, work began to create the Union of the Working Peasantry as a well-remembered form of political organization in the village. This initiative was taken up by the peasants, branches of the STC arose in many volosts of the Tambov, Kirsanovsky, Borisoglebsky and Usman districts.

Nevertheless, the Central Committee of the AKP did not then put forward the task of organizing an armed uprising against the communists and did not overestimate the multiplying facts of peasant revolts. On the contrary, believing that isolated, scattered actions would only lead to the strengthening of the “Red Terror,” the leaders of the Socialist Revolutionaries planned a broad political action of an emphatically peaceful nature. On July 13, 1920, the Central Committee of the AKP adopted a plan for organizing a “sentence movement” in the countryside: following the example of 1905, peasants in their collective “sentences” had to present their demands to the authorities. Therefore, the mass uprising that began a month later under the leadership of A.S. Antonov was, from the point of view of the party center, a disruptive action.

Since A.S. Antonov himself called himself an “independent” Socialist-Revolutionary, the Tambov provincial committee of the AKP demanded that he either stop calling himself a Socialist-Revolutionary, or submit to the party’s tactics. Antonov was asked to abandon the powerless terrorist struggle and move to another region of the province for a peaceful political struggle. Antonov verbally obeyed these instructions, but in practice continued his previous “independent guerrilla tactics.”

In light of the above, it becomes clear that neither the all-Russian nor the provincial leadership of the Socialist Revolutionary Party was directly involved in Antonovism. But the influence of the Social Revolutionaries on the rebel movement, its ideology and organization is undoubted, as is the fact that most of its leaders belonged to the AKP.

The program of the Tambov provincial STC as a whole was a document of broad democratic content with noticeable Socialist Revolutionary influence and with obvious contradictions generated by the specifics of peasant revolutionary ideology. Such a contradiction was the exclusion of the “House of Romanov” and “communists” from among those who were granted the proclaimed democratic rights. In this series is the declaration of the “cessation of the civil war” as the goal of the “armed struggle” waged by the partisan detachments of the STK, in other words, as the goal of the civil war.

Peasant War 1920 - 1921 in Tambov province. grew out of the insurgency that began in the fall of 1918. Subsequent developments were marked by constant outbreaks of revolts in individual villages and the appearance of combat groups and partisan detachments in forest areas, referred to as “gangs” in Soviet documentation. Among the latter, from the beginning of 1919, the “gang” of A.S. Antonov was active in the Kirsanovsky district. The documents from 1919 - the first half of the 1920s, which make up the “Eves” section in the collection, are interesting in at least two respects: firstly, they show how the forces and centers of the future mass uprising were formed, combat detachments arose, leaders emerged, how the dynamics the movement reflected the course of surplus appropriation campaigns, which became increasingly unsustainable; secondly, they indicate that throughout almost all of this time the situation was not irreparable, and there was still an opportunity to prevent a social explosion. In this regard, A.S. Antonov’s letter to the Kirsanov district committee of the RCP(b) in February 1920 is very significant, in which, on behalf of the fighting squad, he declared to “comrade communists” that “we are always ready to give you a hand in the fight against criminality.” help." Evidence of possible interaction and cooperation, a genuine union of revolutionary forces of city and countryside on the brink of 1919 - 1920. can be found in the actions of F.K. Mironov, and I.I. Makhno, and other leaders of the peasant revolution. However, in all cases, the main condition for the implementation of this opportunity was a change in Soviet policy in the villages, primarily the abolition of surplus appropriation.

Understanding of the need to revise the policy towards the peasantry began to arise in the Bolshevik leadership. In the same February 1920, L.D. Trotsky submitted to the Central Committee of the RCP (b) proposals to replace surplus appropriation with a tax in kind, which actually led to the abandonment of the policy of “war communism.” These proposals were the results of practical acquaintance with the situation and mood of the village in the Urals, where in January - February Trotsky found himself as chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic. His note “Basic Issues of Food and Land Policy” began with a fundamental conclusion about the “ineffectiveness of food policy based on the selection of surpluses in excess of the consumer norm,” because it “pushes the peasant to work the land only to the extent of his family’s needs.” Trotsky warned: “Food resources are threatening to run out, against which no improvement in the requisition apparatus can help.” Moreover, maintaining the surplus appropriation system “threatens to completely undermine the economic life of the country.” It was proposed to overcome the process of “economic degradation”: 1) “by replacing the withdrawal of surpluses with a certain percentage deduction (a kind of income tax in kind), in such a way that larger plowing or better cultivation would still be beneficial,” and 2) “by establishing greater consistency between the distribution of industrial products to peasants and the amount of grain they pour out not only to volosts and villages, but also to peasant households.” As you know, this is where the New Economic Policy began in the spring of 1921. Of course, the conditions of the civil war had not yet been eliminated, the inevitability of new military clashes remained obvious, but the limit of the capabilities of the peasant economy had already been exhausted. After the defeat of the main forces of counter-revolution in the East and South of Russia, after the liberation of almost the entire territory of the country, a change in food policy became possible, and due to the nature of relations with the peasantry, necessary. Unfortunately, L.D. Trotsky’s proposals to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP (b) were rejected. The delay in canceling the surplus appropriation system for a whole year had tragic consequences; Antonovism as a massive social explosion might not have happened.

The chronicle of the events of Antonovism is known in general terms and is recreated in detail by published documents. Having broken out in mid-August 1920 in the villages of Khitrovo and Kamenka of the Tambov district, where the peasants refused to hand over grain and disarmed the food detachment, the fire of the uprising spread throughout the province like dry straw, with a speed incomprehensible to local authorities, since they habitually believed that they were dealing with bandit gangs, and not popular indignation. Already in August - September 1920, the Antonovites captured Tambov in a horseshoe, being only 15 - 20 versts from the provincial center. Their number reached approximately 4 thousand armed rebels and about ten thousand people with pitchforks and scythes.

It is difficult to blame the Tambov leadership for underestimating the danger that threatened them. Operational headquarters to combat banditry were immediately created. Already in early September, the provincial committee and the provincial executive committee delegated A.G. Schlichter to Moscow for a personal report, noting that “it was not possible to crush the insurgent movement in a timely manner, which has now grown to enormous proportions and tends to expand, capturing new territories.” Demanding the sending of reliable troops, they warned: “Otherwise we will not carry out the deployment.”

Another significant episode dates back to this time. On September 27, 1920, V.I. Lenin asked the Deputy People's Commissariat of Food, N.P. Bryukhanov: is the allocation of 11.5 million pounds for the Tambov province correct - “shouldn’t it be knocked off?” However, on September 28, a telegram was sent to Tambov with instructions to urgently send two grain routes of 35 wagons each to Moscow. Two days later they reported from Tambov that the emergency government order had been carried out. A short time later, on October 19, 1920, Lenin, in a note to the chairman of the Cheka F.E. Dzerzhinsky and the commander of the Cheka troops V.S. Kornev, categorically demanded: “The speedy (and approximate) liquidation (of Antonovism - Author) is absolutely necessary. Please let me know what measures are being taken. More energy must be shown and more strength must be given."

Initially, the Tambov leadership allocated no more than three to four weeks to liquidate the peasant uprising. The partisan method of conducting combat operations of the rebels, who managed to hide under the onslaught of the Red Army units and simply disappear into the peasant environment, and the pulsating nature of the movement made it difficult to assess the effectiveness of military measures. In a report to V.I. Lenin, V.S. Kornev already stated on November 1, 1920 that from that time on the uprising can be considered suppressed and the whole task in the near future comes down to the liquidation of individual gangs and gangs. Having visited Tambov at the end of December, Kornev, in his own words, became convinced of the impossibility of coping with the rebelling available forces. At this time, over 10 thousand bayonets and sabers were already operating against the rebels.

And subsequently, official documents more than once stated the decline or defeat of the uprising, but it revived again.

There is no doubt about the good organization of the rebels, who formed a kind of “peasant republic” on the territory of Kirsanovsky, Borisoglebsky, Tambov districts with the center in the village of Kamenka. The armed forces of A.S. Antonov combined the principles of building a regular army (2 armies consisting of 21 regiments, a separate brigade) with irregular armed detachments. According to some reports, the Antonovites did not practice mobilization into their ranks, attracting the population only for security, transportation, etc. Such a structure was not strong; between the “atamans” there was often a struggle of ambitions, usual for such formations. But for the time being, this was compensated by the initiative of the commanders, flexible guerrilla tactics of surprise attacks and rapid retreats.

Particular attention was paid to organizing political and propaganda work among the peasants. The army had a network of political agencies that absorbed fragments of the destroyed Socialist Revolutionary organizations. The agitation was of a simplified nature (mainly slogans like “Death to the communists!” and “Long live the working peasantry!”), but very productively played up the difficulties experienced by the village, any miscalculation of the Bolshevik government. This is evidenced by the leaflets and proclamations published in the collection, which are very emotional, but rarely explain the situation, policy, or perspective.

In general, the organization and leadership style of the Antonovites turned out to be sufficient to conduct successful military operations of the partisan type in the conditions of the three forest districts of the Tambov region - in the presence of excellent natural shelters, with the closest connection with the population and its full support, in the absence of the need for deep rear areas, convoys, etc. P. The specificity and clarity of the goals and results of military operations increased the morale of the army and attracted new forces to it: the number of fighters in the Antonov army in February 1920 reached 40 thousand, not counting the “vokhra” (security). But that was the limit. By the beginning of May, their number had decreased to 21 thousand, both as a result of the decisive actions of the Red Army, and in connection with the abolition of food surplus and the onset of the spring harvest. During the “Fortnight of voluntary appearance of bandits” (late March - early April), up to 6 thousand Antonovites showed up and went home en masse.

Attempts to go beyond local boundaries and calls for an all-Russian peasant uprising were futile. The personal qualities of the leaders, their leader-like pretentiousness and limited horizons also had an impact. The Voronezh rebel detachment, led by I.S. Kolesnikov, made its way to the aid of the Antonovites, but soon turned back. According to the Red agents, “they did not agree with Antonov, since Antonov demanded his subordination.” The main thing, however, was something else: the Antonovites were a force only in their districts, close to their home. When the Antonov armies, pressed by troops under the command of M.N. Tukhachevsky, ended up in the Penza province, they were defeated in the first battle. The retreat to the Saratov province did not change anything: a new battle and a new, this time complete defeat. Antonovshchina is a typical peasant uprising with a typical ending - military defeat upon leaving their homeland.

It would be a deep mistake to idealize the peasant war - the “Russian revolt,” although not senseless, but undoubtedly merciless. It caused significant damage to the economy of the Tambov region. The rebels destroyed communications, damaged railways, destroyed state farms and communes, and killed communists and Soviet employees with particular fury. They executed over 2 thousand Soviet and party workers alone (22). Objectively speaking, in terms of cruelty, both sides were not inferior to each other, and cruelty remains cruelty, no matter who it comes from.

The most important milestone in the chain of events was February 1921. By this time, the insurgent movement had reached its greatest extent and began to resonate in the border districts of the Voronezh and Saratov provinces. From that time on, the Soviet government also took decisive action against the Antonovites. The liquidation of the fronts against Poland and Wrangel allowed her to move large and combat-ready military contingents and equipment, including artillery, armored units, and aircraft, to the Tambov region. The tactics of action against the rebels also changed. Instead of separate operations not connected by a single plan, a clear military command structure was created. The entire province was divided into six combat areas with field headquarters and emergency authorities - political commissions.