Petrograd garrison

Petrograd garrison

(until 1914 St. Petersburg), included military units, military schools, commands of military warehouses and institutions that were located in St. Petersburg and its immediate surroundings. It was formed after the construction of the Peter and Paul Fortress (1703). To perform garrison service in St. Petersburg, as a rule, from 2 to 4 regiments were quartered (in ordinary houses) for a period of 1-2 years. In the fall of 1723, the Preobrazhensky Regiment and the Semenovsky Regiment were transferred from Moscow to St. Petersburg and stationed on the St. Petersburg side. In 1725, P. included 2 guards (6630 people) and 4 infantry (about 5.5 thousand people) regiments and naval units (about 14.5 thousand people). The usual area for cantonment of military units was the St. Petersburg side. After the formation of the Izmailovsky Regiment and the Horse Regiment in 1730, the number of guards increased to 9,700 people. Subsequently, the entire guard was concentrated in St. Petersburg. In the 30s and 50s. XVIII century The composition of the P.G. was replenished with cadet corps (Land, Naval, Artillery and Engineering). In the early 90s. There were over 56 thousand military personnel and families in St. Petersburg. The number of P. g. constantly increased. The number of lower ranks alone from 1801 to 1857 increased from 32,800 to 40,900 people. Some of the soldiers and officers of the Moscow and Grenadier Guards regiments and the Guards crew participated in the uprising on December 14, 1825. In the second half of the 19th century. P.G. grew by more than 60%. In 1910 there were about 47.5 thousand people. During the First World War, the composition of the city changed significantly. Cadre regiments (including the Guards) were sent to the front, and their places were taken by reserve formations. The number in February 1917 was 460 thousand people, including about 200 thousand in the capital. Most of the garrison were soldiers of the reserve battalions of the guards regiments (deployed to reserve regiments in the summer) and other reserve units. The proletarian stratum in parts of the city was much higher than in the army as a whole (from 24 to 65%). The transfer of troops to the side of the rebellious workers determined the success of the February uprising against tsarism. In March, the first cells of the Bolshevik Military Organization emerged in parts of the garrison. During the June crisis of 1917, many units went to demonstrate under Bolshevik slogans. In the July Days of 1917, according to official (understated) data, up to 40 thousand soldiers took part in the demonstrations. After the July Days, the Provisional Government sent about 51 thousand people from the garrison to the front. Many active members of the Military Organization of the RSDLP(b) were arrested. Nevertheless, it was the Military Organization of the Bolsheviks that essentially led the struggle of the Poles’ soldiers against the Kornilovism. By the October days, there were over 150 thousand soldiers and officers in the city, with about 240 thousand in the suburbs. On October 24 (November 6), by order of the PVRK, the entire city was put on combat readiness. Soldiers from a number of units took part in the siege and capture of the Winter Palace, and together with the Red Guard repelled the offensive of the Kerensky-Krasnov troops on Petrograd. In December 1917 - February 1918, P. was demobilized. A significant number of former soldiers, non-commissioned officers and junior officers became instructors in the Red Guard and the Red Army, and individual military units became entirely part of the Red Army.

Saint Petersburg. Petrograd. Leningrad: Encyclopedic reference book. - M.: Great Russian Encyclopedia. Ed. board: Belova L.N., Buldakov G.N., Degtyarev A.Ya. et al. 1992 .

See what “Petrograd garrison” is in other dictionaries:

Petrograd garrison- Parade of troops of the Petrograd garrison on Palace Square. Parade of troops of the Petrograd garrison on Palace Square. Spring 1917. Petrograd garrison (until 1914 St. Petersburg), included military units, military schools, military teams... ...

Formed in 1864; before the start of the 1st World War, St. Petersburg Military District. Headquarters of the Petrograd Military District in a building on Palace Square (see Headquarters of the Guards Corps building). On the eve of the 1st World War, the territory of the Petrograd Military District included the territories... ...

Petrograd Military District- Petrograd Military District, formed in 1864; before the start of the 1st World War, St. Petersburg Military District. Headquarters of the Petrograd Military District in the building on Palace Square (see Headquarters of the Guards Corps building). On the eve of the 1st World War, the territory of Petrograd ... Encyclopedic reference book "St. Petersburg"

Revolution of 1917 in Russia ... Wikipedia

- (PVRK), the body of the Petrograd Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies for the practical management of the armed uprising, operating during the period of preparation and conduct October revolution, then (until December 1917) an emergency body... ... St. Petersburg (encyclopedia)

Petrograd garrison

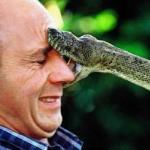

Soldiers and officers of the Petrograd garrison. March 1917

The February Revolution ended by mid-March 1917 with the overthrow of the monarchy and the coming to power of the Provisional Government. The leaders and participants in the coup owe its success - quick and almost bloodless - primarily to the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison.

For some reason, it is generally accepted that at the beginning of 1917 the authorities had no idea that unrest could begin in the country and, first of all, in the capital. In fact, they began to develop a working plan to combat possible riots back in November 1916, and by mid-January 1917 it was ready. It is based on technologies tested during the First Russian Revolution of 1905-1907. The main support of this plan was the police forces (3,500 people) and military units of the capital’s garrison, or more precisely, the training teams of the reserve battalions stationed in the city, preparing reinforcements for the personnel regiments located at the front. None of the plan's developers even dared to imagine that it was these training teams, as well as the reserve companies, that would go over to the side of the rebellious population.

Every betrayal has motives and reasons. The soldiers of the reserve regiments also had them. Both objective and subjective. But more on that a little later, but for now let’s talk about what the Petrograd garrison was like at the beginning of 1917.

The Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) military district was formed back in 1864. Territorially included the lands of the entire Russian north-west plus Finland. That is, about 1/3 of all European territories of the empire. Before World War I, the Guards, 18th and 22nd Army Corps and many military personnel were stationed here educational institutions, individual units like the Life Guards of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Convoy, bodies of the highest military leadership of the army and navy, and much more. In 1915, the district was reformed and turned into a rear area of the Northern Front. As before the war, most units were stationed in Petrograd and its environs. So, in the city itself at the beginning of 1917 there were from 160 to 200 thousand people (Petrograd garrison), in Tsarskoye Selo - more than 40 thousand.

Lieutenant General

Sergey Khabalov

On the eve of the “troubles,” the Petrograd Military District was recreated. Troops numbering 715 thousand were drawn into its orbit. The Petrograd garrison, including units stationed in the Petrograd province (Peterhof, Gatchina, Oranienbaum, Strelna, etc.), numbered 460 thousand. In the summer of 1916, Lieutenant General Sergei Khabalov was appointed head of the Petrograd district (then the rear region of the Northern Fleet). He automatically took command of the Petrograd garrison. On February 19, 1917, when the district was again separated from the Northern Front into an independent military-administrative unit, S. Khabalov began to be called the commander of the air defense. I wonder who recommended that the emperor appoint Khabalov to this difficult position and give him full power in the capital?

The 58-year-old artillery general was an excellent theorist and teacher, but had no combat experience, nor experience in commanding large masses of troops. His combat limit was qualified command of a battalion for 4 months in 1900. The last 17 years of his career - service in the Pavlovsk and Moscow military schools, military governorship in the Ural region. Here is what the mayor of Petrograd, Alexander Balk, remarked about the commander: “General Khabalov, throughout my entire service together, impressed me as an approachable, hard-working, calm person, not without administrative experience, but quiet-minded and without any ability to impress his subordinates and, most importantly, to dispose of troops " Only on March 12, on the fifth day of the uprising, the emperor, who was in Mogilev, at Headquarters, received enough information to assess the scale of the danger. In particular, Minister of War Mikhail Belyaev said that “the state of affairs is catastrophic, that the entire government, as well as the commander of the troops, General Khabalov, are completely at a loss and that if energetic intervention does not follow, the revolution will take on enormous proportions.”

“That same evening, the Emperor ordered the appointment of Adjutant General Nikolai Ivanov (66 years old) as Commander-in-Chief of the Petrograd Military District and to assign at his disposal: the St. George battalion, located at Headquarters, and from the Northern Front two cavalry regiments, two infantry regiments and one machine gun team. Approximately the same outfit was given to Western Front“,” recalled Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich. General Nikolai Ivanov did not have time to carry out the order, since the emperor soon canceled it as unnecessary. It became impossible to correct the situation.

Demonstration of units of the Petrograd garrison

Now is the time to talk about the motives and reasons for betrayal, which will become clear after brief description what happened in the Petrograd barracks and on the Petrograd streets in February 1917.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Petrograd garrison was adequately equipped. Guards units stationed in the capital and surrounding areas were located in modern and comfortable barracks. There was all the infrastructure necessary for life and service. But it was designed for about 50 thousand people. Approximately the same number of regiments of the Guards Corps, minus the infantry division, cavalry and artillery brigade stationed in Warsaw. The frenzy of general mobilization, which engulfed the War Ministry and local logistics institutions, reached its climax by 1917. They dragged everyone they could into the reserve companies. At this time, the military department calculated that the remaining human resource not called up was no more than 1.5 million people. This is in Russia with its 180 million population! The answer is simple. If we subtract the number of soldiers who were at the front, the number of losses and compare the resulting figure with the number of conscripts, it will easily become clear that several million people were “marinated” in the “training” of Petrograd, Moscow, Kiev and other large cities. In inhumane, admittedly, conditions. Because in the company barracks of, say, the Preobrazhensky Life Guards Regiment on Kirochnaya Street, designed for 200-250 people, 2,000, or even more, had to be squeezed in.

It would be a stretch to call the soldiers’ stay in reserve companies training. It is objectively impossible to teach military affairs to such masses of people in a city. And then another problem arrived - a subjective one. Who should I teach? With a shortage of infantry combat officers at the front, where personnel officers in platoon and company positions were replaced by wartime warrant officers, the rear received crumbs. The same green warrant officers who for some reason were not sent to the “front line” and veteran officers discharged from hospitals. Both of them accounted for three or four people per company of 1000-2000 recruits. Sometimes you hear that the elite of the Russian army - the Guard - went over to the side of the rebellious people. Absolute fake. The Guard fought and died at the front. And in its barracks in Petrograd and its suburbs, conscripts who had not managed to become not only guardsmen, but also simply soldiers, found no place for themselves due to idleness. The career guardsmen who returned after being wounded to reserve companies constituted an insignificant minority and could not influence the situation. And some, morally killed by the war, did not want to. Paradoxically, it was also not possible to send this entire mass of people to the front. There would simply be nowhere to put them there, since there were quite enough divisions in the front line, major operations, and therefore, large losses were not expected until May.

Chapter 10

PETROGRAD UPRISING

Introduction. - Labor unrest: reasons. - Street fighting. - Mutiny of the Petrograd garrison. - Crash.

§ 1. Introduction.

On February 23, the emperor returned to Headquarters, and over the next ten days, so many extraordinary and rapidly successive events occurred that they seemed to merge into an inextricable whole. Geographically, however, the drama was limited to Petrograd, Headquarters in Mogilev and the railway route between them. Until the first days of March, the rest of the country hardly knew about what was happening and did not take any part in the revolutionary events. The impressive manifestation of popular feelings, since we are talking about all of Russia, was more a consequence than a cause of the significant changes that took place in its destiny these days. Throughout the entire crisis, there was some time shift between the development of events in Petrograd and the reaction of Headquarters. This led to absurdity: on February 27, the Tsar continued to give orders to his no longer existing government in Petrograd, and on March 2, the generals of various headquarters continued to negotiate with the Chairman of the Duma, as if he could still control events, which in fact was not the case.

As for Petrograd, two phases of events should be distinguished: the first - from February 23 to 28. This period was marked by a rapidly growing wave of strikes in the industrial outskirts and street demonstrations, mainly on Znamenskaya Square, at the eastern end of Nevsky Prospect. The police, with rather lukewarm support from the Cossacks and military units, made half-hearted attempts to disperse the demonstrators. The situation worsened only on the night of 25, when it was decided to use Troops to prevent further demonstrations. The fatalities on February 26 are mainly the result of street clashes and stray gunshots. As the evening approached on February 26, it seemed that labor unrest was weakening, and that the intervention of the troops decided the outcome in favor of the government. The second phase began when the government decided to postpone the February session of the Duma until April; the center of revolutionary events became the Tauride Palace (seat of the Duma).

At the same time, but not in direct connection with the postponement of the Duma session, on the morning of the 27th, unrest spread to the troops of the Petrograd garrison, which significantly changed the situation. The authorities foresaw labor unrest and street riots, and even expected them precisely on these days. In this case, there was a detailed action plan, even if it turned out to be unsuccessful. But against an unforeseen mutiny of the Petrograd garrison there was no automatically effective system of countermeasures. The mutiny of the garrison and the reaction of the Duma to the postponement of the session were the factors that turned the workers' uprisings into a revolution.

Only by the evening of February 27 did the Duma deputies and, independently of them, the committees of the revolutionary parties in Petrograd realize that the time had come for immediate political action. Everyone put forward their own plan to overcome the crisis. These plans were inflated soap bubbles, capturing the imagination of the crowd and distortingly reflecting the rapidly changing moods of the street to burst one after another. In fact, the tsarist government ceased to exist only on the night of February 27-28, and the next morning, Minister of War Belyaev ordered the units that remained loyal to the regime to disperse to their barracks, having first laid down their arms in the Admiralty building, their last combat position. The vacuum created by the collapse of the tsarist government was quickly filled, but the formation of a new government took place under circumstances that are still extremely difficult to restore.

§ 2. Labor unrest: causes.

The strike, which began at Petrograd factories on Thursday, February 23, initially involved 90,000 people. The next day the movement began to expand. On Saturday the 28th, 240,000 workers went on strike. In itself, the fact that the outlying workers were on strike did not carry anything new or ominous. And yet there was something about that February strike that remains unexplained to this day. We attempt to interpret these labor unrest, emphasizing, however - whether our assumptions are considered sufficiently strong or not - that some of the reasons for the strikes are still completely obscure. Admitting that the whole truth is inaccessible to us, we still do not have the right to cover up our ignorance with phrases about a “spontaneous movement” and “the cup of patience of the workers”, which has “overflowed.” These stereotypes only obscure the essence of the matter. A mass movement of such scale and scope was impossible without some kind of guiding force. Even the underground revolutionary committees, which were experienced in this matter and acted according to party instructions, had a hard time mobilizing the workers for smaller actions than in February 1917. Even on the anniversary Bloody Sunday in 1917, workers from 114 enterprises took part in the strike, about 137,536 people in total, and they did not take to the streets. In addition, this day in the industrial areas of Petrograd was considered a non-working day, so it did not require much effort to organize a strike.

Two important reasons were cited for the rapid growth of the strike movement in the last week of February: deterioration in the supply of bread and the lockout at the Putilov plant. As for the first reason, there were indeed some difficulties in delivering bread to bakeries at the beginning of the week. This sparked panic rumors of a flour shortage, increasing demand for bread and lengthening queues, as well as increasing frustration. However, there is solid evidence that there was no shortage of flour. Not once during February did the twelve-day supply of flour for the capital's bakeries fall below the average norm. The main difficulty was distribution, and it could have been easily overcome with good will. But there was none.

For some time now, there had been a quarrel between the Petrograd city authorities and the government over control over the food supply. The city authorities, supported by the Union of Cities and the Progressive Bloc of the State Duma, insisted that the food supply to the citizens of the capital should be in their hands, and the Minister of Internal Affairs Protopopov, although he did not have the necessary means for this, wanted to take on this additional responsibility. , which caused new attacks on him in the press and in the Petrograd City Duma and created a general atmosphere of a food crisis. In addition, rumors about the introduction of grain standards hit the popular imagination hard, especially since bread is the main food product in Russia. They were afraid not only that there would be little bread, which in itself caused protest from the peasant or worker, but they were also frightened by the thought that some kind of boss would be able to control the amount of bread that a person puts into his mouth. Apparently, the influx of customers into bakeries was partly due to the desire to stock up on crackers.

In addition to the infighting over who would manage food supplies, there were two other factors that could actually lead to a shortage of bread in bakeries and unrest in bread lines. They said that some bakers, instead of baking bread from the full quota of flour allotted to them, sent some of the flour to the provinces, and there it was sold for good money on the black market. The rumor of abuses forced General Khabalov to introduce strict supervision of bakeries. Secondly, we cannot neglect the possibility of deliberate sabotage on the part of the bakers. Petrograd bakers were united into a fairly strong Bolshevik faction. During labor unrest in the winter of 1915-16. Bakeries played a significant role in the strike movement in the capital. This is evidenced by a letter written in early March 1916 by Pavel Budaev, a member of the Bolshevik Party and the St. Petersburg Bakers' Union, to his friend, also a baker, in Siberia. Budaev talks about a bakery strike organized by the Bolsheviks on the Vyborg side: on Christmas Day 1915, the police demanded that bread be sold on the first day of Christmastide, but bakery workers did not go to work for two days, and bread appeared on sale only on the third day. On January 9, all factories went on strike, “taking up the initiative of the Vyborg side.”1

Although complaints about the lack of flour and bread in February 1917 were not very justified, nevertheless the crowd chanted the slogan “Bread!” and during the first three days of the riots he figured on the banners of the demonstrations. This slogan suited cautious organizers of street demonstrations like Shlyapnikov and, unlike the other two slogans of those days - “Down with war” and “Down with autocracy” - it had a particularly effective effect on the troops called in to disperse the demonstrations. They refused to shoot at a crowd that was “only asking for bread.”

In addition to rumors of food shortages, the main reason for the workers' demonstrations in February 1917 is often cited as the lockout at the Putilov plant. The circumstances that led to a similar action in February 1916, and the role played by the “Leninists” in this matter, have been described above.2 In both cases, riots began in the workshop, whose workers demanded an exorbitant increase in wages. Our source of information about the riots of 1917 was not a police report, but a request sent to the Prime Minister, War and Navy Ministers by thirty members of the Duma, including the Trudoviks, A.I. Konovalov and I.N. Efremov.3 According to this document, the workers of one On February 18, the workshops of the Putilov plant asked for a 50% increase in wages. It is significant that when they put forward such an exorbitant demand, they did not first consult with their comrades who worked in other workshops. The plant director flatly refused, and then the workers staged a sit-in strike. After a meeting between the administration and representatives of workers from other workshops, a 20% increase was promised. But at the same time, on February 21, the management fired the workers of the striking workshop. This repressive measure caused the strike to spread to other workshops, and on February 22 the management announced the closure of these workshops for an indefinite period. This meant that thirty thousand well-organized workers, most of them highly qualified, were literally thrown out onto the street.

The lockout contributed greatly to the spread of strikes. Following established practice, workers went from factory to factory and used all possible means, including intimidation, to convince their comrades to join the strikers. Arriving just in time, for the agitation of the workers had reached its limit due to rumors of food shortages, the call for a strike, as well as the call to demand a sharp increase in wages, acted without fail. The ability to get lost in large crowds during strikes and demonstrations provided a wide field of activity for agitators.

Later, in the twenties, Soviet historians of the labor movement, for example, Balabanov, tried to explain the avalanche of strikes in February 1917 by the end of a long process of accumulation of forces and the growth of class solidarity among workers. The purpose of these historiographical constructions is to prove that the development of the revolutionary movement with its struggle for political rights was preceded by economic struggle and the growth of class consciousness. Real events did not quite correspond to this exemplary construction of Marxist social dialectics. Judging by what we know about the activities of underground revolutionary organizations among the Petrograd workers, not one of them was ready for a systematic revolutionary action at this particular moment. When on February 22, factory workers discussed the organization of Women's Day on February 23, V. Kayurov, a representative of the St. Petersburg Bolshevik Committee,4 advised them to refrain from isolated actions and follow the instructions of the party committee.

But imagine my surprise and indignation when the next day, February 23, at an emergency meeting of five people in the corridor of the plant (Erikson), Comrade Nikifor Ilyin announced a strike in some textile factories and the arrival of female worker delegates with a statement about our support for metalheads.

I was extremely outraged by the behavior of the strikers; on the one hand, there was a clear disregard for the resolution of the district party committee, and then - he himself had just last night called on the female workers for restraint and discipline, and suddenly there was a strike. There seemed to be no purpose or reason, except for the particularly long lines for bread, which in essence were the impetus for the strike.

And indeed, at the beginning of 1917, the Petrograd Bolsheviks did not really know how to react to the increase in labor unrest. The Bolsheviks' attempt to start a civil war, recorded in the above-cited leaflet of the Petrograd Committee, failed in February 1916. Since then, the prospects for revolution in war time seemed dubious to the Bolshevik leaders. We see that in the critical days before the explosion of labor unrest at the end of February 1917, the Petrograd Bolsheviks behaved cautiously. They warned the workers against partial and isolated strikes, since this gave the factory owners and the government the opportunity to disperse the working masses and jeopardize the success of the revolution in the future. Like Miliukov and the Duma liberals, they believed that the most favorable moment for the revolution would come immediately after the end of the war. It took them 48 hours to realize that, contrary to their warnings, the labor movement had assumed unexpected dimensions, and only then did they begin to call for the creation of a revolutionary government.

The insignificance of the role that the Bolsheviks played in the revolution of 1917 does not in itself surprise us. With the exception of Shlyapnikov, their leaders in the capital were inexperienced and lacked authority.5 Soviet historians of the revolution clearly understood this. Only after Pokrovsky’s school was liquidated in the early thirties did Soviet historiography take the view that the wisdom of the Bolsheviks and the impeccability of their policies played an important role in the February events and that the role of other, non-Bolshevik, workers’ and revolutionary organizations was insignificant. It is not surprising that in the Soviet Union there was so little material about the activities of other revolutionary organizations in Petrograd. Of course, the right-wing Mensheviks could not lay claim to leadership of the workers. Their organization was connected with the working group of the Military-Industrial Committee, which ended up in prison on February 27, 1917, and it is very doubtful that Gvozdev could in any way influence the outbreak of labor unrest on February 23-25.

However, in Petrograd there was another Social Democratic organization, the activities of which are very superficially described by Soviet historians, and only they have access to the necessary archives. This was the so-called Interdistrict Committee, otherwise Mezhrayonka, an association of worker delegates from different industrial districts of the capital. This organization became especially active during the war, at one time it was headed by Karakhan.6 The influence of Trotsky and the experience of the St. Petersburg Soviet of 1905 played an important role in the composition and ideology of this organization. In August 1917, Trotsky and the entire organization of the Interdistrict Committee united with the Bolsheviks, and from that moment on, its former members tried not to remind that the organization initially, before uniting with the Bolsheviks, played an independent political role, because this could damage their reputation. On the contrary, every more or less prominent member of Mezhrayonka assured that at heart he had always been a Bolshevik, and the independence of the organization was a tactical device dictated by the conditions of underground work under the tsarist regime.

It seems, however, that in February 1917, no revolutionary group made as much effort to persuade the working masses to take to the streets as Mezhrayonka. M. Balabanov reports that Mezhrayonka issued leaflets with slogans - “Down with autocracy,” “Long live the revolution,” “Long live the revolutionary government,” “Down with war.”7 If so, then this proves that the stake is on the revolution, from which after the failure of 1916, the Bolsheviks refused, it was made and won with great success by the Mezhrayonka.

Yet it is difficult to believe that such a small revolutionary group as the Interdistrict Committee could organize a labor movement of such magnitude without any help. In addition, its leaders apparently did not have a firm determination to implement the slogans contained in the leaflet. Yurenev, who then headed the Interdistrict Committee, participated in informal meetings that took place after February 23 in private homes between Duma liberals, representatives of the legal opposition and underground revolutionaries. So, on February 26, Yurenev surprised V. Zenzinov (right Socialist Revolutionary) at one of these meetings in the apartment of A.F. Kerensky in that “he took some kind of amazing position.”8 By this time, the revolution was already in full swing, and clashes between troops and crowds took place throughout the city. However, Yurenev, in contrast to everyone else present, not only did not show any enthusiasm, but, says Zenzinov, “poisoned us all with his skepticism and disbelief.” “There is no and there will be no revolution,” he stubbornly insisted. “The movement in the troops is fading away and we must prepare for a long period of reaction.” He especially sharply attacked A.F. Kerensky, reproaching him for his “usual hysteria” and “usual exaggeration.”

We argued, Zenzinov continues, that the wave was rising, that we must prepare for decisive events, Yurenev, who considered himself on the left flank, tried hard to pour cold water on us. It was clear to us that this was the position at that moment not only of him personally, but also of the Bolshevik St. Petersburg organization. Yurenev spoke out against forcing events, argued that the movement that had begun could not succeed, even insisting on the need to calm the agitated working masses.

Zenzinov's memoirs were written many years later, but this does not mean that they are incorrect. Yurenev’s attitude towards the meeting can be logically explained in different ways: he met with representatives of liberal circles who were ready to establish first contacts with the revolutionary movement, and he had reasons to cool their ardor and desire to “lead the revolution” and become leaders of the working masses - this role was not played by anyone a social democrat would not want to share with representatives of the bourgeoisie. On the other hand, it is possible that on February 26, Yurenev was indeed frightened by the prospect of a clash between the Petrograd workers and the garrison; he was as disgusted by street battles as Shlyapnikov, who held the same post in the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee that he himself held in Mezhraionka. The Mezhrayonka had the beginnings of its organization in the Petrograd garrison, but, apparently, it was weak, and nothing so far indicated that discontent had spread to the army.9 No one had yet heard of the mutiny of the Pavlovsky regiment. The revolutionary committees at this moment had every reason to fear a clash with armed units, but they could, without losing anything, wait for the end of the war. The legal opposition, both in the Duma and in public organizations, sought to use the situation created in the capital to achieve its goal. For them, this chance to get the long-awaited constitutional reform was perhaps their last. If you miss an opportunity, the war may end in the summer, and then everything will be lost. Zenzinov points out the impossibility of convincing Yurenev, but Yurenev probably wanted to put the liberals in their place and make them understand that the Petrograd proletariat will not fight in the streets in order to rake in the heat for them with their own hands. He, of course, was well aware of the reasons for the sympathy for the revolution on the part of those who hoped to use the revolution to force the Tsar to make concessions and seize power. But even if we consider the categorical pessimism of the leaders of underground revolutionary organizations to be a political maneuver aimed at maintaining control over the labor movement, it is still difficult to reconcile it with the militant grasp of the party ideology prescribed to all political figures of social democracy. Militancy, obviously, was lacking among both the Bolsheviks and Mezhrayonka. And yet the labor movement grew, and demonstrations on Znamenskaya Square and Nevsky Prospekt became increasingly difficult to disperse. It is difficult to believe that such a movement could not lose its drive and cohesion without any organization or leaders agitating and rousing the masses. The theory of the spontaneous movement of the Petrograd proletariat is only a recognition of our inability to explain the course of events. Why should such a movement begin then, and only then, in Petrograd? Neither before nor after this did the working masses of Russia demonstrate such a capacity for concerted “spontaneous” actions.

Regarding the driving factors of events, there is another aspect of the February Revolution that requires study. We are talking about the alleged role of German money and German agents. In the debate about German assistance to the Bolsheviks after Lenin's return, the issue was obscured and hushed up. We have already stopped at this. There are two independent problems - German intervention in the February events and German assistance to the Bolsheviks. And both are equally difficult for a historian to resolve. From the very beginning, all participants in the case were keenly interested in not leaving any documentary evidence. On the German side, when access to the archives was opened, something became clear, but on the Soviet side, nothing changed, not a single document became available, and any questions there would be considered a political provocation, an insult to doctrine.

In Russia at that time, many apparently were convinced that the Germans somehow had a hand in the February events. At one of the first meetings of the Provisional Government, in March, Foreign Minister Miliukov casually mentioned the role of German agents and money in the February Revolution. There followed a sharp attack from Kerensky, who left the meeting room, declaring that he could not be there “where the sacred cause of the revolution is being violated.”10 Of course, Kerensky distorted and exaggerated, shouting that Miliukov was “being violated,” Miliukov simply expressed the generally accepted Opinion. The hidden springs of the popular uprising require explanation, and the intervention of German agents provides an explanation for this amazing success of a “revolution without revolutionaries.”

In one of the previous chapters we tried to look at how the various German military departments intensified to contribute to the organization of labor unrest and, perhaps, revolution. We have seen what Gelfand (Parvus) developed for German authorities detailed Gshan, offering at their service his extensive connections both in the Balkans and in Scandinavia, and that the German government gave him significant financial support so that he could independently carry out his revolutionary plans. If we return to political events in Russia, then very few traces of Gelfand’s activities are found there, although there are some indications that German money and Gelfand’s ingenuity were not in vain.

We saw above that the strike that broke out in Petrograd in January 1916 was provoked and supported financially by Helphand's organization, and perhaps the same agents organized the strike in Nikolaev. With these precedents in mind, it is difficult to believe that the Germans had nothing to do with the events of February 23-26, 1917, which were so reminiscent of the events of 1916. We also saw that in 1917 Helphand's organization was still operating in Copenhagen, and Helphand's economic and financial position was better than ever. None of his agents in Russia (ten people are said to have worked for him) were caught.

It is possible that the factions he supported changed between February 1916 and February 1917. And the more faceless Mezhrayonka played, apparently, a more important role in 1917 than the Petrograd Bolshevik organization. Helphand, who had close connections with the left Mensheviks and with Trotsky, could choose to support one committee or another. But this is just a guess. Neither Gelfand nor the other participants in this activity left any evidence that this was really the case. One might suspect, however, that the all-important question of strike financing (that is, supporting the workers week after week while they went on strike, putting forward either impossible economic or impossible political demands that the factory management could not satisfy) was settled by impersonal strike committees with the help of funds , the source of which was Gelfand’s organization.12 And the more impersonal and inconspicuous the committees and people providing support, the better for the conspiratorial structure of Gelfand’s organization.13

Although German agents and German money may have been behind the labor unrest in February 1917, it would be a mistake to exaggerate their influence on subsequent events. As soon as the demonstrators, emerging from the outskirts of Petrograd, mixed with the crowd in the city center, the nature of the movement began to change. The slogans with which the demonstration began on the industrial outskirts were changed or discarded as soon as contacts began with the inhabitants of the center - students and high school students, minor employees, junior officers and other representatives of the middle classes who were ready to gawk at the demonstration of workers, join the procession, sing revolutionary songs and listen with taste to street speakers. First, the workers came out with slogans: “Bread!” - “Down with autocracy!” - "Down with war!" We have already seen that the food situation hardly justified the first slogan. The second was common for any demonstration in Russia. Along with the red flag, it testified to revolutionism. But the third slogan, which played a large role in the labor demonstrations of February 23-26, deserves further clarification.

The chronicler of the Russian revolution, Sukhanov, believes that the slogan “Down with war” can be considered as evidence of the spread of the ideas of the Zimmerwald Conference among the proletarian masses. But even Sukhanov had to admit that it was a mistake to put forward such a slogan at a moment when the protests of the workers in the outskirts turned into a nationwide revolution, in which the bourgeois opposition parties were supposed to play a leading role. He comments:

It was a priori clear that if we count on bourgeois power and join the bourgeoisie to the revolution, then it is necessary to temporarily remove slogans against war from the queue, it is necessary at this moment to temporarily fold the Zimmerwald banner, which has become the banner of the Russian and, in particular, the St. Petersburg proletariat.14

If we leave aside the Marxist jargon that Sukhanov uses when describing Russian events 1917 (“proletariat”, “bourgeoisie”), then his analysis is completely correct. It is true that the slogan: “Down with war” did not attract the middle-class crowd in the center of Petrograd. Paradoxically, this class suffered much more from ever-increasing inflation and other war hardships than the workers. Salaried employees had a harder time keeping up with rising prices than regular wage workers. Nevertheless, the middle classes did not lose their patriotism and were generally deaf to the defeatist ideas of Zimmerwald, and it was Patriotism that forced them to join the decisive onslaught against the autocracy. They completely succumbed to the propaganda of the liberal press, the Duma and public organizations and welcomed the fall of the tsarist regime, because they thought that the tsarist government would either be defeated in the war or conclude a shameful separate peace. Therefore, the slogan “Down with war” shocked them; it could easily have led to a split in the revolutionary movement if the organizers of the demonstrations had not removed it at the initial stage. The St. Petersburg Bolshevik Committee can hardly be accused of putting forward this slogan. In their proclamations of the previous year, the Bolsheviks refrained from any anti-war calls. Mezhrayonka, apparently, included the slogan in its leaflet in February 1917. In Mezhrayonka they should have known well why the Bolsheviks did not use this slogan, and understood what was “a priori clear” to Sukhanov, namely, that from the point of view of revolutionary tactics the slogan was a gross mistake.

But, as can be calculated from other considerations, if the strike movement was started by those who received instructions from Berlin, Copenhagen and Stockholm, then this slogan had meaning. The people who spent their employers' money on encouraging such demonstrations were primarily interested in the destruction of Russian military power and the Russian spirit; they were not interested in the prospect of revolution, nor were they interested in the need to maintain a semblance of national unity in the form of overthrowing the centuries-old political system. It was important for Helphand's unidentified agents to ensure anti-war demonstrations that did not deviate from the main goal. And the “proletarian masses” cared little about what slogans they demonstrated under, as long as money was coming from the funds of the strike committees - in all likelihood, from the same people who inscribed the slogans on the banners. Sukhanov writes very vividly about the cynicism of such proletarian revolutionaries, allowing us to assume that the slogans were imposed on them by some mysterious outsiders. On Saturday the 25th Sukhanov met a group of workers discussing the events. "What do they want?" - one of them asked gloomily. "They want peace with the Germans, bread and equality for the Jews." Sukhanov was delighted with this “brilliant formulation of the program of the great revolution,” but did not seem to notice that the gloomy worker imagined that the slogans did not come from him and others like him, but were imposed by some mysterious “them.”

In reality, the Zimmerwald banner that Sukhanov speaks of was carried not only metaphorically, but also literally. Right Socialist Revolutionary Zenzinov was on Znamenskaya Square on February 25 and recalls the following scene:

Now the crowd was already pouring in a thick mass along Nevsky - all in one direction, towards Znamenskaya Square, and as if with some specific purpose. Homemade red banners appeared from somewhere - it was clear that all this happened impromptu. On one of the banners I saw the letters "R.S.D.R.P." (Russian Social Democratic Labor Party). The other one read “Down with War.” But this second one caused protests in the crowd, and it was immediately withdrawn. I remember this quite clearly. Obviously, it belonged either to the Bolsheviks or the “Mezhrayontsy” (adjacent to the Bolsheviks) - and did not at all correspond to the mood of the crowd.15

Zenzinov is probably not entirely fair to the Bolsheviks. Defencism, as we will see, penetrated even among the Bolshevik leaders. Lenin, when he returned to Russia in April, needed all his political sophistication to again restore the anti-war slogan (but no longer in the crude formulation of the February days), first in the party program, and then in the consciousness of the “proletarian masses”. Nevertheless, anti-war slogans and anti-war speeches pronounced from the pedestal of the monument to Alexander II on Znamenskaya Square in the first three days of labor unrest should be considered evidence of the direct intervention of German agents, and not the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee as such.

§ 3. Street fighting.

It is surprising how little importance was attached to the demonstrations of February 23-25 by those most affected. Strikes in industrial areas, with demonstrations, the singing of revolutionary songs and the sporadic appearance of red flags among the crowds, were taken for granted, no one thought that all this could affect the course of major political events in the near future. There was no mention of demonstrations in the Duma debates; The Council of Ministers, which met on February 24, did not even discuss the demonstrations. The ministers believed that this was a matter for the police, not politics. Even the revolutionary intelligentsia of Petrograd, who were not directly involved in underground work, were not aware of what was happening. Mstislavsky-Maslovsky, an old Socialist-Revolutionary militant who had previously published a manual on street fighting (he now served in the library of the General Staff - such was the careless tolerance of the autocratic government!), says in his memoirs that the revolution, “long-awaited, desired,” found them , “like the foolish virgins of the gospel, sleeping.”16

Of course, the police were ready. But the demonstrators, who initially numbered in the thousands, now numbered tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands, and the police called in the troops available in the capital to maintain order. However, police action was slow. There were not enough police officers, and not only little was done, but no more could be done to prevent the accumulation of people in the streets and squares. As soon as a crowd gathered somewhere, the police dispersed it, and, under threat of arrest, people dispersed along side streets and into the courtyards of neighboring buildings. But as soon as the police left, the crowd gathered again in the same place, and slogans and speeches resumed. Both demonstrators and police, with few exceptions, did not cross certain boundaries. It happened that demonstrators overturned a tram, but they made no serious attempts to build barricades. It is characteristic that even in the days of subsequent street fighting between the opposing sides, the front line was never established. The revolutionary masses and government troops closed in.

Since the weather was unusually cold, both the crowds and the police went home for the night, only to take up the seemingly aimless competition with renewed vigor in the morning. On Sunday the 26th, demonstrations began later - just after noon. And no one took advantage of the night to capture and hold strategic points in view of future battles. Neither side seemed to see anything catastrophic or simply serious in what was happening.

Sporadic outbreaks of violence and shootings in different parts cities in the first days of the revolution cannot be considered the result of a deliberate decision either on the part of the police and army, or on the part of the revolutionary committees. It is clear that government troops were ordered to fire into the crowd only in self-defense. The very thought of those killed and wounded on the snow-covered streets of the capital horrified the authorities. What will the allies think? It was assumed that the Cossacks would disperse the crowd with whips, but since they were going to war, they did not have this part of the equipment. When this became clear, an order was issued to provide them with money so that everyone could get a whip for themselves. And the empress, in one of her letters to the sovereign, assured that there was absolutely no need to shoot at a crowd consisting of nasty boys and girls who were taking advantage of the difficulties in supplies to commit mischief. The order not to shoot allowed the crowd to approach the soldiers and talk to them. The soldiers soon understood the mood of the crowd. It seemed to them that the demonstration was peaceful and it would be a sin to use weapons against it. There was very little ammunition available, and no steps were taken to ensure there would be sufficient supplies in case serious street fighting broke out. This created the most fundamental difficulties when on the 27th a mutiny broke out in the garrison and it could only be stopped by armed suppression.

At the same time, even the Bolshevik leaders seemed to be doing everything in their power to prevent shootings in the streets. Shlyapnikov speaks out quite definitely on this issue. When workers demanded that he arm the demonstrators, he flatly refused. It’s not difficult to get a weapon, he said, but that’s not the point:

I was afraid that the tactless disposal of weapons acquired in this way could only harm the matter. An inflamed comrade who used a revolver against a soldier could only provoke some military unit and give the authorities a reason to set soldiers against the workers. Therefore, I resolutely refused to seek weapons for everyone; I most urgently demanded that the soldiers be involved in the uprising and that in this way all the workers could obtain weapons. It was more difficult than acquiring several dozen revolvers, but it was a whole program of action.17

Despite the determination of both sides to avoid the use of weapons, shootings occurred throughout the city, and the number of wounded and killed increased daily. This is partly due to mutual suspicion. In Petrograd they firmly believed the rumor that the police had installed machine-gun posts in the attics residential buildings and is preparing to shoot at demonstrators from these covers. Any shooting, especially at a distance, was immediately attributed to machine gun posts. Later, the revolutionaries sent special squads to search houses and arrest policemen shooting from rooftops.

The provisional government created several commissions to find out what role the police played in the February battles. Subsequently, historians analyzed all the available data, but did not establish a single case of police officers sitting on rooftops firing at a crowd with machine guns. Nevertheless, the legend of the “protopopov’s machine guns” played a role in angering the police and in provoking excesses in which a large number of officers and lower police officials were killed.18

This anger explains a number of clashes that occurred on the eve of Sunday 26 February. However, in order for a clash to occur, some kind of provocation is needed on the part of the organizers of the demonstrations. Bombs were thrown at military detachments, and they, in defense, immediately used weapons. But even in these cases, many believed that the bombs were thrown by police agents provocateurs. This is confirmed by a conversation between the Chairman of the Duma and the head of the Petrograd garrison. Rodzianko was firmly convinced that a policeman had thrown a bomb at I1schidents like those mentioned, and he told Khabalov so. “The Lord be with you! What is the point of a policeman throwing grenades at the troops?” - Khabalov answered in surprise and somewhat naively.19

On the 25th, a serious incident occurred on Znamenskaya Square. It is rightly considered a turning point in the initial phase of the uprising. Several eyewitnesses, among them the Bolshevik worker Kayurov and V. Zenzinov, gave different accounts of what happened, although no one witnessed the murder itself. A large crowd gathered around the monument Alexander III, from the pedestal of which, as in previous days, revolutionary speeches were spoken. Just in case, a detachment of Cossacks was sent to the square, but the Cossacks did nothing to disperse the demonstration. At approximately 3 o'clock in the afternoon, a detachment of mounted police arrived at the scene under the command of an officer named Krylov. Following the established practice of dispersing demonstrations, he pushed through the crowd to grab the red flag, but was cut off from his unit and killed outright. According to Zenzinov, he was shot, and it was proven that the bullet came from a Cossack rifle. According to Martynov,20 who used materials from the police archive, Krylov was killed with a bladed weapon and then received several saber blows. An autopsy did not reveal a gunshot wound. Kayurov describes a terrible scene, how the demonstrators finished off Krylov with a shovel, and the crowd enthusiastically picked up the Cossack who hit Krylov with a saber.

But no matter who killed Krylov - the crowd or the Cossacks - everyone, both the police and the demonstrators, had the impression that the Cossacks on Znamenskaya Square had joined the rebels. This case of the Cossacks’ attitude towards clashes between the police and the crowd was not the only one. How did this change happen? After all, in general, Cossack troops were considered extremely reliable, since it was a question of suppressing peasant or worker revolts. A possible answer may be found in the memoirs of Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, whose personal influence in the days that followed was as important as it was invisible.

V.D. Bonch-Bruevich was an old Bolshevik who supported Lenin at the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Party in 1902, since then their connection has not been interrupted. During and after the 1905 revolution, he actively participated in the organization of the Bolshevik underground press. When the revolutionary wave began to subside in 1906, Bonch-Bruevich, instead of emigrating like most Bolshevik leaders, remained in Russia and worked at the Academy of Sciences, researching Russian religious sects and their literature. He thoroughly studied the psychology and social composition of sectarians, in particular, the sects known as Old and New Israel. He even published one of the sacred books of these sects, the so-called Dove Book, and earned the gratitude of the adherents.

Bonch-Bruevich says in his memoirs that in February he received a deputation of Cossacks from the regiment stationed in Petrograd, who wanted to talk with him about religious issues. After a ritual embrace, which was a secret conventional sign among initiates of the New Israel sect, the Cossacks asked Bonch-Bruevich what they should do if they were sent to suppress the uprising in Petrograd. Bonch-Bruevich told them to avoid shooting at all costs, and they promised to follow his advice. He subsequently learned that the detachment that sent the deputation was patrolling on Znamenskaya Square on critical days and was involved in the murder of a police officer. Bonch-Bruevich's discreet hints explain how secret contacts were established between revolutionary intellectuals and disoriented Cossacks who left their fields and villages to go to war, and found themselves in the turmoil of the revolution in the great Babylon of the north.21

Despite the fact that the general situation in the capital had deteriorated by the end of the last week of February, reports sent to Mogilev by the commander of the Petrograd Military District Khabalov, Minister of War Belyaev and Protopopov were falsely encouraging. Events in the capital were interpreted as disorganized, anarchic agitation, a mixture of food riots and hooliganism; the reports expressed confidence that the measures taken would put an end to all this within twenty-four hours. These measures consisted of tightening control over bakeries, arresting about a hundred revolutionaries - including a significant part of the members of the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee - and replacing the Cossack detachments, which lukewarmly supported the police, with cavalry units.22

However, by this time the tsar was probably already concerned about the situation in Petrograd. His assessment, although not entirely accurate, was still closer to the truth than what could be read in the reports of his ministers. On the evening of the 26th, Khabalov received a telegram from the tsar, which said: “I command you to stop the riots in the capital tomorrow, which are unacceptable during the difficult time of the war with Germany and Austria.” The telegram was composed by the sovereign himself and sent without consultation with anyone. She led Khabalov into complete confusion. Even if we allow for some exaggeration of his testimony during interrogation at the Muravyov Commission, Khabalov’s testimony obviously quite accurately reflects his state after receiving the telegram. He told the commission:

This telegram, how can I tell you? - to be frank and truthful: she hit me hard... How to stop “tomorrow”... The Emperor commands to stop at all costs... What will I do? how can I stop? When they said, “Give me some bread,” they gave you some bread and that was it. But when the flags have the inscription “Down with autocracy” - what kind of bread will calm you down! But what to do? - The Tsar ordered: we must shoot... I was killed - positively killed! Because I did not see that this last resort that I would use would certainly lead to the desired result...

At approximately 10 pm on February 25, a meeting of responsible police and army officials was held, whose task was to maintain order in the capital, and Khabalov gave the order:

Gentlemen! The Emperor ordered the riots to stop tomorrow. This is the last resort, it must be used... Therefore, if the crowd is small, if it is not aggressive, not with flags, then you are given a cavalry detachment in each area - use the cavalry and disperse the crowd. Since the crowd is aggressive, with flags, then act according to the regulations, i.e. warn with a three-time signal, and after a three-time signal, open fire.

Later, when the decision was already made to dissolve the Duma, Khabalov made a report to the Council of Ministers.

February 26 was Sunday. The city, as before, was calm at night, there were no military patrols, and on Sunday morning the workers sat at home. However, the events of the past day forced the police authorities to gather the policemen, distribute them into platoons and arm them with rifles. In the morning, Khabalov reported to Mogilev that the city was calm. Shortly after noon, while this message was traveling to Headquarters, a serious uprising broke out, still concentrated on Znamenskaya and Kazan Squares. The riots did not last long and were suppressed by troops using firearms. There were many wounded and killed, although in the picture of Nevsky strewn with corpses, which we find not only in the fantastic description of Trotsky, but also in Sukhanov, there are many exaggerations.24

However, it is difficult to exaggerate the impression that the shooting made on the soldiers themselves. Over the past three days, they had been on the streets, seen the crowds, talked to the women and youth who had joined the demonstrators, and saw that their commanders were hesitant to resort to violence to disperse the crowds. When they were finally ordered to open fire on the same, mostly unarmed, crowd with which they had just fraternized, they were horrified, and there is no reason to doubt General Martynov’s assessment of the situation: “The overwhelming majority of the soldiers were indignant at the role they they had to play, suppressing the uprising, and shot only under duress."25 This especially applied to the training team of the Volyn regiment, which consisted of two companies; the unit had two machine guns, and it, on the orders of Major Dashkevich, was supposed to disperse the demonstration on Znamenskaya Square . As a result, the crowd fled, leaving forty dead and the same number wounded on the pavement.26

There were shootings, dead and wounded in many other places in the city, and by the evening of the 26th the police authorities, summing up in official jargon, could say that “order had been restored.”

In view of what happened the next day (Monday the 27th), it must be said that one incident on February 26th eclipses all clashes between police and demonstrators. We are talking about a revolt of soldiers in the Pavlovsk Guards Regiment. On Sunday, two companies were sent to patrol the streets and took part in the shelling. The officers probably had them quite under control, and there were no signs of insubordination. The demonstrators rushed to the Pavlovsky barracks, asking the reserve company of the regiment to come out and stop the shooting at the crowd carried out by the patrolling companies, after which some of the soldiers (in all likelihood, there was no officer control) poured out into the street with rifles, demanding an end to the bloodshed. The disorder continued until the officers appeared, began negotiations with the soldiers and then, with the help of the regimental chaplain, sent the soldiers back to the barracks.27 This incident was reported to Khabalov and the Minister of War Belyaev, and it naturally caused some consternation . Belyaev insisted on immediate measures and proposed immediately executing the rebels. Khabalov argued that the case should be considered by a military court. For now, the soldiers' weapons were taken away and they were locked in the barracks. It turned out that twenty-one rifles were missing. The soldiers seemed to be depressed and betrayed the instigators - nineteen people - who were arrested and sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress. Apparently, the incident was settled and did not affect the morale of the other companies. It was the Pavlovsky regiment that appeared on the 27th with weapons and an orchestra to defend the headquarters command of the district, when the troops almost lost control and many detachments of the Petrograd garrison “joined the people.” It is interesting to note that the Petrograd military authorities did not immediately inform Mogilev about the fact of the mutiny.

It now seems strange to us that this incident did not serve as a warning to the officers of other units guarding the city. This can be explained to some extent by the special conditions of service in the capital. A soldier in the Petrograd garrison served on average from six to eight weeks. A constant point of irritation was the issue of vacations. The idleness and boredom of the crowded barracks forced the soldiers to ask to go to the city, while the officers were mainly concerned with keeping them in the barracks, since it was difficult to keep track of them in the troubled waters of Petrograd life. The number of some companies reached one and a half thousand people; there were young recruits there - just boys, who had not yet taken the oath to the banner and the sovereign, there were also soldiers who had been at the front, who spent a lot of time in hospitals due to wounds or illness; this made everything boring, and the lack of discipline in the hospitals corrupted it. Among them were many Petrograd intellectuals who worked as soldiers in artillery factories, and through them some of the underground propaganda penetrated into the soldiers’ environment.28

The morale of the soldiers was greatly affected by the thoughtless and senseless manner in which they were used during the first three days of the street riots. In accordance with the developed plan to maintain and restore order in the capital, they were forced to stand for hours at strategic points, without being given specific instructions on what to do in the event of unrest. The soldiers understood that the authorities were reluctant to use firearms against the crowd. They also understood that the police, when they could not cope on their own, looked to them for help, which they were reluctant to provide because their relationship with the police was already strained.29

There was already contact between demonstrators and soldiers, and this sometimes led to troops siding with the demonstrators against the police. When the Tsar's order radically changed the situation and when, on the afternoon of the 26th, the troops were ordered to shoot at the demonstrators, they were naturally stunned. In the end, the crowd behaved as it always did when its behavior was tolerated. And yet, if we leave aside the incident in the Pavlovsky regiment, there were no clear cases of disobedience among the soldiers that day, and, as we have already noted, even the chairman of the Mezhrayonka Yurenev believed that the attempt to start a general revolutionary uprising had failed, that the army was against the rebels won't join.

§4. Mutiny of the Petrograd garrison.

At the moment when the radical and revolutionary intelligentsia was already losing faith in the success of their cause, a new factor came into play. The soldiers of the Volyn Regiment, who took part in the shooting on Znamenskaya Square on Sunday, February 26, did not sleep in their barracks, discussing what was happening. These were soldiers of two companies of the training team, and their commander, Captain Lashkevich, ordered to open fire on the crowd. One of the non-commissioned officers of the regiment, a certain Kirpichnikov, distinguished himself that day - he snatched a homemade bomb from the hands of one demonstrator and, with a sense of duty, handed it over to the police.

Kirpichnikov subsequently turned out to be the most energetic propagandist of “defencism” among the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison. In his account of what happened, Kirpichnikov describes Lashkevich as an unpopular officer, wearing gold glasses (note this symbol of wealth and intelligence), cruel, rude, insulting and bringing even old soldiers to tears, his nickname was “spectacled snake.”30

As the officers left the barracks, the soldiers gathered to talk about the day's events. They did not understand why they were ordered to shoot. Kirpichnikov does not report the details of the conversation that took place in the dark barracks, and even if he did, it would still give little, because reality turned into a legend before it had time to come true. There is nothing to suggest that the soldiers' sudden decision not to shoot at the demonstrators was prompted by revolutionary conviction. It was prompted rather by a natural disgust for everything that the most unpopular officer orders. At the same time, they were obviously aware of the risk they were exposed to by deciding to disobey. Whether this was the work of some representative of revolutionary groups or another secret organization, we do not know. Taking into account what follows, we cannot rule out this possibility. Kirpichnikov, whom the soldiers apparently considered the leader, was unlikely to be a member of such a group.

The situation became explosive the next morning, Monday the 27th, when the soldiers went out into the corridors of the barracks to line up and Lashkevich appeared. The first company of the training command greeted him as usual, and he made a short speech, explaining to the soldiers what their duty was, and quoting the sovereign's telegram. Then Kirpichnikov reported that the soldiers refused to go out into the street. According to Lukash, who reports Kirpichnikov’s words, what happened next was like this: The commander turned pale, recoiled and hurried to leave. We rushed to the windows, and many of us saw that the commander suddenly spread his arms wide and fell face down into the snow in the courtyard of the barracks. He was killed by a well-aimed random bullet!" When these lines were written, common sense had already been replaced in Russia by the fantastic logic of revolutionary rhetoric. The murder of Lashkevich is sometimes attributed to Kirpichnikov himself. The night before, the commander of the Pavlovsky regiment, Colonel Eksten, was killed at the door of the barracks, after being subdued mutinous company. Subsequently, officers were rarely killed by the soldiers they commanded. Generally speaking, it was the murder of the commander that had the most revolutionary effect on soldiers and sailors. This was the doctrine adopted by the Bolshevik Party and Lenin himself.31

Whoever killed Lashkevich, this brought more revolutionism into the consciousness of the soldiers of the Volyn Regiment than any propaganda. The soldiers suddenly felt that there was no return for them. From that moment on, their fate depended on the success of the rebellion, and this success could only be ensured if others immediately joined the Volyn regiment. After some hesitation and discussion on the training ground, the soldiers grabbed their rifles and rushed outside to the barracks of the Preobrazhensky and Moscow regiments. The news of the mutiny of the Volyn Regiment spread like fire through the streets, where, bypassing patrol posts, workers were already gathering from the outskirts to continue the demonstration that had begun the day before. Soldiers of the Volyn Regiment fired into the air and shouted that they supported the people. But very soon they ceased to be a single whole, mingling with the demonstrators and becoming part of the very crowd that was so characteristic of those days - unarmed, disheveled soldiers and armed workers in caps and even hats.

The officers of the rebel units were nowhere to be seen. On this decisive day, February 27, the behavior of the officers of the Petrograd garrison had great consequences. In most cases, they did not know their soldiers well, their authority was supported only by traditional discipline, to strengthen which there was no personal effort on their part. But even those who knew the soldiers well, who had advanced and even progressive views, like Colonel Stankevich, to whom we owe one of the first voluminous works on the revolution,32 immediately felt great personal danger when they heard that soldiers were killing officers in the barracks. In addition, many officers of the Petrograd garrison also succumbed to the propaganda of the press and public organizations and wanted negotiations with the Duma and immediate constitutional reform, no matter how late they were.33

The mutiny of the Volyn regiment, which quickly spread to other parts of the Petrograd garrison, was, of course, key event on this day - Monday 27 February. After the fall of the tsarist regime, in the intoxication of the first weeks, it seemed that the mutiny of the garrison was a manifestation of the will of the people for revolution. With the advent of the new government, it became an article of faith to believe that even in these first days (February 27 - March 2) any military unit faced with the alternative - to join the revolution or participate in its suppression - would enthusiastically join the people at the first opportunity. Events in Petrograd do not confirm this.

First of all, it is quite obvious that the government did nothing to raise the morale of those units that were ready to obey orders. On Monday, February 27, around noon, Minister of War Belyaev ordered General Zankevich to take under his command the remaining loyal parts of Petrograd to help General Khabalov, who had completely lost his head. Zankevich had at his disposal a large detachment, which he gathered on the square of the Winter Palace. The soldiers enthusiastically greeted his speech, in which he called on them to stand firm like a rock for the Tsar and the Fatherland. But after that, hours passed, and no order came; no one bothered to feed the patrol troops, and as dusk fell, the soldiers went to their barracks to have dinner. Along the way they were absorbed by the crowd.

Typically, neither Khabalov nor Belyaev knew which units they could count on. Thus, in the barracks of Sampsonievsky Prospekt there was a Samokatny battalion, consisting of ten companies - two rifle, four forming and four reserve. They had 14 machine guns at their disposal. The cyclists were literate people, they understood mechanics, but they later said that “a lot of petty-bourgeois elements had crept into their midst.” They were commanded by a very popular officer named Balkashin. When he ordered sentries around the barracks on February 27, the soldiers immediately obeyed him. He tried several times to contact the headquarters of the Petrograd Military District, but to no avail. Only at 6 o'clock in the evening did he decide to withdraw his company from the street and lock himself in the barracks. At night, he once again tried to contact headquarters, but the soldiers he sent did not return. He managed, however, to replenish the supply of ammunition by sending a cart to the battalion headquarters on Serdobolskaya Street. The Scooter Battalion put up vigorous resistance in its barracks, which were just wooden houses, on the morning of February 28th. When it became obvious that the barracks would be destroyed by machine gun and artillery fire, and Colonel Balkashin realized that it was impossible to break through, he decided to surrender. He ordered a ceasefire, left the barracks and addressed the aggressive crowd, saying that his soldiers were doing their duty and were innocent of the bloodshed and that he alone was responsible for ordering the soldiers to shoot into the crowd out of “loyal feelings.” In response, shots were fired, one bullet hit Balkashin’s heart, and he died immediately. This seems to have been the only case of exceptional bravery noted in Petrograd during these days.34

The case of the Samokatny Battalion35 shows what a determined and popular officer could have done if the headquarters of the Petrograd garrison had been less disoriented. The feelings of the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison were definitely divided, and, apparently, there was more than one occasion when they clearly did not want to be involved in actions that they considered a riot. The first memoirs of that time, published in the Soviet Union, reflect this fact, although later they began to constantly keep silent about it. For example, the worker Kondratyev, a member of the Petrograd Bolshevik Committee, recalls in his memoirs36 how he went with the workers and rebels of the Volyn Regiment to the barracks of the Moscow Regiment, where several officers and lower ranks barricaded themselves in the officers' mess and fired at demonstrators across the training ground. Kondratyev and those who were with him burst into the barracks and saw that the soldiers were depressed, unarmed and did not know what to do. No exhortations from the revolutionaries had any effect. “Straining his vocal cords to the limit” and shouting until he was hoarse, Kondratiev set an ultimatum - if the soldiers did not support the “cause of the people,” the barracks would be immediately shelled by artillery. According to Kondratyev, this threat had an effect on the soldiers, and they took their rifles and went out into the street. This incident was undoubtedly typical of what happened that day in Petrograd; he explains why neither the self-appointed headquarters of the rebels (under the command of the Socialist Revolutionaries Filippovsky and the above-mentioned Mstislavsky-Maslovsky) nor the military commission of the Duma Committee (led by Colonel Engelhardt) had troops at their disposal for most of the day, although thousands of armed soldiers switched sides revolution. Soldiers who went out into the streets preferred to get lost in the crowd rather than remain visible in their units. They sold rifles to the highest bidder, decorated their greatcoats with scraps of red ribbons, and joined one demonstration or another, smashing police stations, opening prisons, setting fire to courthouses, and engaging in other forms of bloodless revolutionary activity.

The mutiny of the Petrograd garrison took the local military and civil authorities by surprise. It completely destroyed the system of maintaining order on which the government relied. When developing this system, the authorities believed that clashes would be limited to firefights between

soldiers and demonstrating workers. In this regard, the city was divided into sections, and a specific regiment was assigned to each. This system lost all meaning since the district headquarters no longer knew which units it could rely on. The reaction of the officers to the first news of the soldiers' mutiny shows the extent to which their instability, fed by propaganda, as well as newspaper and liberal verbiage, extended. The officers of the Volyn Regiment were completely confused. One of them described what happened at the regimental headquarters when the officers came to Colonel Viskovsky, the battalion commander.37 Having learned what had happened to Captain Dashkevich, Viskovsky began to confer with his adjutant. From time to time he went out to the officers who were waiting in the next room for orders and instructions. He asked about the details of what happened. The officers gave various advice and suggested calling the cadets. Such advice from subordinates went beyond what was accepted and was a violation of military discipline. Until 10 o'clock the rebels remained on the parade ground, apparently not knowing what to do next. At this point, the mutiny could have been suppressed, but the senior officer continued to hesitate and repeat to his subordinates that he believed that the soldiers would remain faithful to duty, come to their senses and hand over the instigators. When the mutinous company left the barracks yard, the battalion commander advised the officers to go home and left himself.