I. Genealogical classification of Indo-European languages by A. Meillet.

IN COMPARATIVE HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS

1. Genealogical classification of Indo-European languages by A. Meillet.

2. Typological classifications of languages.

3. The problem of reconstructing the Indo-European proto-language.

4. Languages-centum and languages-satәm.

Genealogical classification reflects the study of languages from the point of view of their material community as a result of development from one common source.

In his “Introduction to the Comparative-Historical Study of Indo-European Languages,” A. Meillet examines 10 language groups:

1) Hittite 6) Celtic

2) “Tocharian” 7) Germanic

3) Indo-Iranian 8) Baltic and Slavic

4) Greek 9) Armenian

5) Italian 10) Albanian

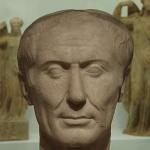

Hittite- the most ancient of known to science written Indo-European languages, the language of the Hittite kingdom (XVIII-XIII centuries BC).

"Tocharian" language established from fragmentary texts (translations of Buddhist texts of the 7th century) found in China.

The oldest representative Indian languages – Sanskrit. About 25 modern Indian languages. Hindi is one of state languages India.

Iranian languages. Two ancient written languages: Avestan and Old Persian. Avestan language preserved in the religious text “Avesta”, written monuments Old Persian language date back to the 6th–5th centuries BC.

Modern Iranian languages: Tajik,Ossetian,Kurdish,Afghan. Unwritten Iranian dialects are widespread from the Pamirs to the Caspian Sea.

Meillet notes that in their oldest texts the Indo-Iranian languages present the least distorted face of Indo-European morphology, so a comparative grammar of the Indo-European languages arose only when Greek, Latin and Germanic languages were compared with the Indo-Iranian languages.

Greek group: Achaean, Ionian and Attic dialects. Achaean the dialect was widespread in Cyprus (V–IV centuries BC), Ionian dialect - in Asia Minor (VI-V centuries BC). Introduction to attic The dialect is provided by the texts of Plato and other literature of the 7th century. BC. The Attic dialect was spoken by educated people - the upper classes of Athenian society. The Attic dialect became the basis of the Greek common language (IV century BC), to which the dialects of modern Greek go back.

Main representative Italian groups – Latin language . It has been known since the 3rd century. BC. as the language of high Roman society, which was strictly standardized. Along with the formation of new European nations, a group was formed independent languages, which, according to Meillet, are modifications of the Latin language.

Group of Romance languages: Italian,Spanish,French,Portuguese,Romanian,Moldavian.

In the sixteenth century. European colonization gave new distribution to these languages: Portuguese in Brazil, Spanish in the rest South America and Central America, French in Canada and Algeria. Meillet: “The speech of the city of Rome covered vast territories in almost all parts of the world.”

Celtic group: Gaulish, Brittonic and Gaelic languages. Gaulish language was widespread in the northern part of modern Italy, the language of the ancient Gauls, supplanted by the Latin language. Brythonic language (Breton And Welsh dialects) spread throughout Great Britain, but was later replaced by English. Gaelic, represented by Irish literature since the 7th century, exists today in certain regions of Ireland and Scotland.

Three groups Germanic languages : Gothic, North Germanic and West Germanic.

Gothic language is an ancient written language. It is recorded in texts - translations of the Bible (VII century).

North German group: Icelandic,Norwegian,Swedish,Danish.

IN West German group Meillet distinguishes several dialects.

High German dialects have been recorded in monastic literature since the 9th century. They are characterized by great fragmentation and differ significantly from each other. High German dialects became the basis of the national German language.

Low German dialects served as the basis for the formation of a national Dutch (Dutch) language.

Written monuments on Old English, which has spread across much of the UK, belong to the 9th century. Together with the formation of the English national market in the 16th century. a national English language, which later spread to North America, Australia and other parts of the world.

Baltic group: Lithuanian And Latvian languages that, according to Meillet, are not much different from the languages of the 16th century, to which the texts preserved in them date back. Old Prussian language known only from one dictionary of the 15th century.

Slavic languages Meie divides into 3 groups: southern, Russian and western.

Southern group: Bulgarian,Serbian, Macedonian.

Western group:Polish, Czech, Slovak. Polabian language was widespread in the lower reaches of the Elbe and fell out of use in the 18th century.

TO Russian group Meillet attributes Russian And Ukrainian languages. At the same time, he notes that Russian dialects are very close to each other. The most noticeable differences characterize only the Belarusian dialects, common in the west of the Russian-speaking area.

Albanian known since the 16th century. Meillet notes that a significant part of his vocabulary consists of words borrowed from Latin, Greek and Slavic languages.

The most ancient written monuments on Armenian language date back to the 5th century. Its vocabulary contains many borrowings from Iranian languages, but, according to Meillet, it still forms a separate branch in the Indo-European family of languages.

In conclusion of his description of the Indo-European languages, Meillet emphasizes that the historical feature of these languages has always been their ever-increasing spread, which occurred through the conquest of territories and colonization with the subsequent displacement of the language of the conquered conquerors.

II. Typological classifications of languages.

The comparative historical method of studying languages contributed to the emergence typologies– a science that studies the similarities and differences in the structural features of related and unrelated languages. The task of typology in the 19th century: the establishment of a system of linguistic (language) types and the distribution of all known languages world according to these types. The result was typological classifications of languages that are used in linguistics to this day.

Classification August Schleicher is based on the fact that languages express grammatical meaning differently, which Schleicher calls “attitude,” contrasting it with “meaning,” denoting lexical meaning with this term. The lexical meaning is always expressed by the root of the word, and there are roots in all languages. Therefore, based on the expression lexical meaning it is impossible to establish linguistic types. Grammatical meanings can either not receive expression at all in the structure of the word, or they can be expressed, but different ways. Depending on this, Schleicher establishes 3 linguistic types.

(1) Languages in which the “attitude” is not expressed in the structure of the word are classified by Schleicher as insulating(root) type. In isolating languages, the word has no affixes. It can be monosyllabic, i.e. consist of one root, or polysyllabic, consisting of several roots. The languages of Sino-Tibetan belong to the isolating type. families.

(2) Languages in which the “attitude” is expressed in the structure of the word by an affix specially intended for this purpose are classified by Schleicher as agglutinating type. These languages are Turkic and Finno-Ugric, as well as Japanese and Korean.

(3) Languages in which “attitude” is expressed not by a special part of the word specifically intended for this purpose, but by means of internal inflection, i.e. by changing the root vowel, Schleicher refers to inflectional type. First of all, these are Semitic languages families.

Schleicher calls the doctrine of language types morphology, and its classification - morphological, borrowing this term from natural science, where it means the science of the structure and morphogenesis of plants. This classification is largely based on the ideas Wilhelm von Humboldt , who formulated the foundations of the classical typology of languages. He introduced the concepts of isolating, agglutinating and inflectional languages. But besides these language types, Humboldt considers another type of language, which he calls incorporating.

The peculiarity of incorporating languages is that the roots are combined into a single whole, which is both a word and a sentence. Humboldt calls such a whole an incorporating basis, using the Latin term “incorporation” (“inclusion”). In incorporating languages, a word includes a sentence. Humboldt includes Indian languages in America and Paleo-Asian languages as such languages. languages spoken in northern Asia.

The most significant clarifications in the typological classification of languages of the 19th century. were contributed by an American linguist Edward Sapir . His typology of languages covers three classifications, each of which has its own criterion for identifying linguistic types: (1) types of concepts expressed in language; (2) the technique of expressing these concepts; (3) the degree of syntheticity of the language.

Classification by types of concepts

Sapir considers 4 types of concepts that can be expressed in language, and places them on a scale from the most concrete to the most abstract concepts:

(1) Specific concepts (concepts of objects, actions, qualities, states) are expressed by the root of the word.

(2) Derivational concepts (concepts related to word formation) are implemented in the language with the help of affixes that clarify the meaning of roots. For example, the concept of “doer” in the word teacher or the concept of “small degree” in the word whitish.

(3) Specific relational concepts are even more abstract in comparison with derivational concepts. They reflect the grammatical meanings of words associated with their semantics. For example, tense and modal meanings of verbs, gender and number meanings of nouns.

(4) Purely relational concepts are the most abstract. They have nothing to do with the semantics of words, but contribute to their connection in speech and the creation of sentences. For example, case relations, meanings of motivation, statement or question.

Concrete and purely relational concepts are expressed in all languages, since they represent aspects of the language such as vocabulary And syntax. Vocabulary and syntax exist in all languages. Derivative and specific relational concepts are reflected in morphology, and morphological features in different languages are present to varying degrees. Therefore, Sapir saw all the differences between languages in this regard in the presence or absence of concepts of the 2nd and 3rd types.

Sapir divides all languages, firstly, into complex And simple, which respectively have or do not have derivational concepts, secondly, on mixed-relational And purely relational, which respectively have or do not have specific relational concepts. He classifies the languages of the Sino-Tibetan family as simple and purely relational languages, and most other languages as complex and mixed-relational languages.

Classification according to the technique of expressing concepts

Sapir calls the “technique” of expressing concepts the method of implementation in language grammatical meanings. Depending on the way in which grammatical meanings are expressed in a language, Sapir distinguishes 4 language types: isolating, symbolic, agglutinative and fusional. This classification has many similarities with the typological classifications of the 19th century.

Insulating« technique" is characteristic of the languages of the Sino-Tibetan family, but also in other languages, for example, in English and French, it is used to express relational concepts.

Symbolic« technology"Sapir calls internal inflection and examines it using the example of Semitic languages, primarily Hebrew. Examples of “symbolic technique” can also be found in Indo-European languages, in particular English and German.

Agglutinative And fusional languages use different affixes to express grammatical meanings. The fusion "technique" differs from the agglutinative "technique" in that it involves a close union of the affix and the root, which causes a change in the root. For example, in Russian the infinitive suffix -th after vowels it is added to the stem in an agglutinative way, but after consonants the same suffix appears in the form -ti, causes changes in the final consonants of the root: gree b y – gre With you, meh T y-me With you, ve d y – ve With you. In cases such as bake – oven, shore - take care fusion is observed in pure form, when the suffix cannot be separated from the root. Sapir calls languages in which fusion predominates over agglutination fusional, and languages in which only agglutination is observed agglutinative.

Classification by degree of synthesis

Depending on the degree to which grammatical meanings are combined in one word, Sapir classifies all languages into 3 types.

(1) Analytical Sapir refers to a language in which there is rarely a combination of grammatical meanings in one word. In such a language, the word becomes closer to the morpheme (languages of the Sino-Tibetan family, French and English).

(2) Synthetic Sapir calls a language in which several grammatical meanings are always combined in one word. In such a language, the word occupies a middle position between morpheme and sentence (all ancient written Indo-European languages, as well as Arabic, Turkic languages, Slavic and Baltic languages).

(3)Polysynthetic Sapir calls a language in which a very large number of grammatical meanings are combined within a word. In such a language, the word comes closer to the sentence (Indian and Paleo-Asian languages).

Sapir presented the results of his research in a summary table, where he characterized 21 languages from three named points of view, i.e. summarized his three classifications. In his table: Chinese – a simple, purely relational language of isolation technique and analytical method of synthesis; French– a simple, mixed-relational language of fusion technique and analytical-synthetic method of synthesis; English language– complex, mixed-relational language of fusion technique and analytical method of synthesis; Sanskrit And Latin language– complex, mixed relational languages of fusion-symbolic technique and synthetic method of synthesis.

The typological classification of languages by E. Sapir is considered the most detailed of all existing ones, therefore it has received the greatest response in modern linguistics.

Research into the reconstruction of the primary source of Indo-European languages was started by Franz Bopp. In the XIX – early XX centuries. they were continued by famous comparatists August Schleicher, Karl Brugmann, Antoine Meillet.

August Schleicher named the primary source of the Indo-European languages proto-language (Ursprache), and the hypothetical restoration of sounds, words and forms of this language is its reconstruction. There are no written records of the proto-language, but Schleicher was convinced that it was possible to reconstruct it and show how the Indo-European languages developed from its forms.

In general terms, the structure of the Indo-European proto-language was presented to Schleicher as follows:

(1) A simpler sound composition than in modern languages, which was characterized by strict symmetry: the number of sounds in general, as well as the number of vowels and consonants, were multiples of three (15 consonants, 9 vowels, 24 sounds in total).

(2) Words were divided into names and verbs. Subsequently, individual case and verbal forms were transformed into adverbs, prepositions and particles.

(3) The word consisted of a monosyllabic root and a suffix or several suffixes.

(4) The name had the grammatical categories of gender, number and case (3 genders, 3 numbers and 9 cases).

The proto-language reconstructed by Schleicher was only a rough approximation to the actually existing ancestor of the Indo-European languages. But the reconstruction method itself turned out to be fruitful and has found wide application in linguistics.

According to Carla Brugmana , the original source of the Indo-European languages was not monolithic, but was a collection of dialects. He believed that it was possible to recreate individual facts of the proto-language, but not the language as a whole.

Restoring phonetic facts, Brugman established 73 sounds in the proto-language (27 vowels and 46 consonants). In the field of morphology, he obtained a complex picture of the various means of expressing the grammatical categories of the verb. Describing various shapes name, he noted the presence of 3 genders and 3 numbers in the proto-language, which coincided with Schleicher’s conclusions. But Brugman allowed only 7 cases for the names of the proto-language.

Point of view Antoine Meillet : by comparing languages it is impossible to restore an extinct language, therefore no reconstruction can represent the original source of the Indo-European languages as it really was. He proposes to study not individual linguistic facts, but to compare the systems of different Indo-European languages.

Meillet advocated the use of the comparative historical method to establish correspondence systems between related languages. In this case, one must begin with correspondences in the field of phonetics, since sound relationships between languages of common origin are subject to phonetic laws that are easily formulated.

Meillet proposes to analyze not only sound, but also semantic coincidences of words in different languages. Meillet rightly considered grammar to be the most stable part of the language system. In this area, he attached particular importance to the study of the so-called “irregular” forms, which include, for example, verb conjugation forms be. They have great evidentiary power in establishing connections between related languages and the proto-language from which they originated.

On the one hand, Meillet was skeptical about the fact of reconstruction of the Indo-European proto-language, considering it a set of correspondences, but on the other hand, he sought to establish the composition of the sounds and forms of the proto-language.

According to Meillet, the history of languages is determined by a combination of two processes: the process of differentiation, i.e. division of the Indo-European proto-language into separate dialects, and the process of unification, i.e. the unification of dialects into separate languages that currently make up the Indo-European language family.

IV. Languages-centum and languages-satәm.

In comparative historical linguistics of the late 19th century. Particular importance was attached to the division of Indo-European languages into 2 approximately equal groups: centum languages and satәm languages.

Languages-centum: Greek, Latin, Celtic, Germanic.

Languages-satәm: Indian, Iranian, Slavic, Baltic, Albanian, Armenian.

The basis for dividing Indo-European languages into these groups was the established difference in the behavior of back-lingual consonants. It is assumed that in the Indo-European proto-language there were two series of such sounds: back-lingual palatal and back-lingual labial. Palatal sounds were preserved in the ligatures-centum as velar consonants, and in the ligatures-satәm they were transformed into sibilant consonants [s], [z].

Numeral notation 100 in Latin and Avestan languages were established as labels for the names of the corresponding language groups.

Labial back-lingual sounds retained labialization in centum languages and lost it in satәm languages.

Currently, the noted sound features of centum and satәm languages are given no more importance than other phonetic correspondences, but in the 19th century. they served as the basis for putting forward the hypothesis about the existence of two centers in the history of Indo-European languages: one in Europe with centum languages, the other in Asia with satәm languages. Later studies refuted this hypothesis.

WITH full version The books can be found by following the link:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/75867453

The most consistent reconstructions of archaic forms are carried out in the works of Gamkrelidze \2\ and Savchenko \31\ (see also Audrey \37\). We will immediately translate many of the results of their reconstructions, presented in the form of ordinary rectangular phoneme tables, into the sector-triadological forms of recording developed here, which will allow the reader to get used to more complex structures appearing later (see Conclusion to this chapter and Appendix C).

The vocalism of the Indo-European language, according to \2\, is formed by a system of three short (e\a\o) and three long (e:\a:\o:) vowel sounds, constituting a correlated three-term model of oppositions according to the differential articulatory features of the row (front row \ middle row \ back row), represented as:

A - o

\ / ; ; ; [w]

e

[y]

Which can be transformed within the framework of the method of oriented triads into the formula in Fig. 3.

In classical Indo-European studies, the presence of initial laryngeal protophonemes (A\E\O) is assumed, from which the basic system of Indo-European vowels developed.

The conditions for maximum distinctiveness of sounds suggest that these phonemes occupied (theoretically) an average, symmetrical position in the range of basic sound tones (which is reflected in the indicated formula for the vowels of the proto-language: these are phonemes of average rise). Note that in modern languages, the main vowel protophonemes are considered long and have short duplicates. On the other hand, modern versions of these phonemes most likely differ from their prototypes both in shift in row (for example, the middle row (a) in some later languages is assigned to the front or back row) and in rise (in most modern languages(a) are classified as low rise, as the most open phoneme) as a result of the redistribution of features between them and newly formed non-syllabic phonemes (formed from syllabic sonants or semivowels, for example: w\y according to the scheme indicated in the figure) in various historical versions and .-e. proto-language.

In the process of development of the proto-language, the vowel system expands to 5 short phonemes (or up to 10, if we take into account their long duplicates) in Proto-Slavic (и\е)(а)(у\о) or up to 13 phonemes in Old French (or 21 vowels in English, where numerous diphthongs are taken into account). As can be seen from Fig. 3, the triadic formula of vocalism of the proto-language allows on average 9-12 main distinguishable vowels of the first order (with 3 vowels actually implemented), which occupies a middle position between the two ancient languages being compared. Over time, both the outermost low vowels (a) and the outermost high vowels (u|y) and (i|и) are additionally formed in all languages, as a result of the transformation of semi-consonants into vowels. According to \38\ these phonemes can be considered as vocalic versions of half-consonants and, perhaps, originated from later transformations of half-consonants (u) and (i) like Аu;w,u(у),v, Ai;j,i(и) . Physically, this is acceptable if both vowels and semi-consonants have the same formant structures (and if they are articulatory close). With the isolation of extreme phonemes in sectors of tonal ranges, intermediate phonemes become extremely unstable and are subject to various changes in rise.

Over time, with the transformation of the proto-language, nasalized (nasal) vowels are distinguished in individual languages, which constitute separate subsystems from oral ones both among sonorant (m\n) and among syllabic sonants (for example, ancient Slavic yus). We emphasize that since nasal (and sonorant in general) constitute intermediate phonemes between vowels and consonants (since these are vowels generated from the corresponding nasal syllabic sonants), their structure (system of correlations of intragroup oppositions) coincides with the structure of the original phonemes. One of the goals of this part of our analysis is precisely to prove that the structures of all phonemic subsystems of the languages under consideration, despite their apparent diversity, are of the same type and are controlled by one structural code of the Indo-European proto-language.

In the early archaic period of the existence of the protolanguage, short and long forms of vowels, apparently, were not distinguished. In a more developed period, such a separation occurred, presumably with the disappearance of the so-called posterior lingual laryngeal (h) \31\ from the high-frequency range of the acoustic spectrum. The hypothesis of three laryngeals (h1\h2\h3) in the proto-language provides an interesting mechanism for the emergence of long vowels. According to the ideas of Jerzy Kurylovic \31\, if the vowel was in the postlaryngeal position, then after the reduction (disappearance) of the laryngeal position it became a short vowel. The prelarynx position produced a long vowel (He>e\ ...\eH>e:). This was a general phenomenon that affected both vowels and consonants: after the disappearance of the back-lingual laryngeals, the preceding phonemes (s, d) were lengthened. Lengthening vowels makes them long, and lengthening consonants either softens it or gives it a hint of aspiration: CH>Ch.

Another feature of archaic vocalism was the significant predominance of the high-frequency front-lingual vowel e over lower-frequency vowels (a\o), which were manifested in vernacular and expressive vocabulary. Perhaps the expressive (a) was used in the language of the Indo-European hymn-singing priests.

On the other hand, the velar laryngeals (h1\h2\h3) were transformed into the velar aspirate sound h, which determines the subsequent velarity of all aspirates in various languages \31\. Perhaps the disappeared laryngeals acted as an intersyllabic copula and, when they disappeared, were vocalized (chc>cvc), giving i: h>i, (pel-h-men > par-i-man - abundance) and transforming neighboring vowels according to the above rules. Perhaps these laryngeals acted as a conjunction (and) in a sentence, which led to their disappearance.

Next to the vowels in terms of expressiveness and sound in the proto-language were the sonorant syllabic Rv (classical ancient Greek er, al; ancient Slavic nasal yuses and diphthongs from semivowel and vowel, such as ja, jo, ju), followed by sonorant consonants, which included semivowels (i\ u\…), tremulous\smooth (r\R\l) and voiceless nasals (m-labial\ n-forelingual\ ;-palatal). The general meta-structure of the sonorant phonemes of the R proto-language is shown in Fig. 4.b.

In various versions of modern i.-.e. language, this structure has generally been preserved. The changes affected mainly the subsystem of semi-consonants, which either completely disappeared (Slavic languages) or expanded to three phonemes (ј\;\;), as in common Germanic languages. The tremulous subsystem was also partially transformed, which in the same common Germanic languages acquired the laryngeal (R). On the other hand, the original semivowels in certain positions gave rise to fricatives \31\: (;>в\ ј>;) – in Slavic languages, Ancient Greek and Latin (see Appendix C).

Among the actual consonant phonemes of the proto-language of the archaic period, three occlusive oral voiced phonemes of the main series stood out most and were structured already in the archaic period: dental d; labial b; backlingual (palatal) g, which constitute a triad based on these characteristics (d\b\g). These main phonemes, in turn, were tripled according to secondary series of classification features (ringing\deafness\aspiration): d;(d\t\dh), b;(b\p\bh), g;(g\k\gh).

By identifying a separate sector in the oriented triad for each sign (ringing - in the lower, southern sector, deafness - in the left, western, aspiration - in the right, eastern) we introduce the main phonetic triads:

Phonetic triads of stop phonemes according to the characteristics (voicelessness\aspiration/ringing) of the main model and in the model of guttural stops of the proto-language.

There is a well-established opinion that in the archaic period the main oppositions of consonants were not a voiceless/voiced sound, but a strong or weak sound. It seems sufficient for us to confine ourselves to the period of language in which the supposed contrasts of deafness and ringing have already been developed.

Stop consonants differ in place of articulation: dental (dental) - d\t, labial (labial) - b\p and back-lingual (palatal) - g\k. According to these signs, more high level all three triplets of stop noisy consonants can be combined (according to the method of articulation) in the following formula (Fig. 4.a):

Fig.4.a Fig.4.b

stop noisy T consonant sonants R

In fact, by deriving the formula in Fig. 4.a and highlighting oppositions of the type in the phonological series: deafness\aspiration\ringing (p\ph\b, t\th\d, k\kh\g, etc.); according to the method of articulation of oppositions such as (tooth\lip\palate) - (t\p\k), (d\b\g), (th\ph\kh), etc., they established a certain hierarchy of oppositions. We assumed that oppositions of the second type are less significant, and they are characteristic of a smaller number of phonemes. On the other hand, the central role in the formation of the core of the cyclic phonetic system, ring structure It is not the series of simple binary correlations d\b, d\g, b\g, etc. that play, but triple interphonemic correlations of the type (d\b\g), (d\t\dh), etc. The arrows indicate the beginning and direction of the formation of the triadic hierarchy of phonemes in the indicated substructures. In this case, the author proceeds from the fact that on average from the triad (T\Th\D) (for example, in the Roman name Gr\a\kh) all voiceless phonemes T are the shortest (they have a high proportion of noise and, as a result, they are more high-frequency), aspiration lengthens voiceless phonemes. The longest of this triad are the voiced components of D, which have maximum sonority. For modern i.-e. languages, the following relationship between the duration of voiceless and voiced components is typical: 2tt = td, i.e. deaf ones are half as long as voiced ones (or they have twice the main range of carrier frequencies). It is possible that such a situation existed in the archaic period of the proto-language.

In some way, the special position of labials in i.e. in the proto-language is determined by the very weak and low-frequency position of the voiced bilabial labial b \100, p. 105\. On the other hand, there is a high frequency of the voiceless labial p, which is also restored to the labial voiceless for all modern i.-e. languages other than Old English, where p; f. For the Proto-Slavic area, such a bilabial phoneme is clearly restored in a large number of examples.

From the latter it is clear that the Russian form of the indicated word with a clearly expressed labial (b) at the beginning of the word is close to the original one, I.-e. form. On the other hand, the weakness of the voiced labial in the front position for the western area of the I.-E dialects. the proto-language is also fixed.

Thus, for stop phonemes i.-e. parent language is established overall ratio for the duration of their pulses tc \see. L.V. Bondarko, 52\:

A) tt< tth < td; tp < tph < tb; tk < tkh < tg;

Tt< Tp < Tk;

The last chain of inequalities establishes a hierarchy of features according to the method of articulation, where we proceed from the fact that the highest-frequency impulses (with the maximum frequency range or on the basis of sonority - with the maximum admixture of noise) in the pre-archaic period were realized by the front-lingual phonemes T (dental). On the other hand, it is the dental ones that are the most common of the three types of phonemes under consideration in modern French and German. Palatal phonemes K (with all other parameters being the same) are the narrowest (among dental and labial ones) and the least common. Labial P (p\ph\b) occupy an intermediate position in terms of the frequency of their use in the language (in dictionaries and texts). The fact that palatal phonemes are located at the lower level of this hierarchy is beyond doubt and is noted in the dictionaries of almost all the ancient and modern languages we used, where complexes (tk), (pk), (bg), regularly appear in the initial consonantal part. (dg)…

With the establishment of hierarchical relationships between dental T and labial P for i.-e. In the proto-language everything is somewhat more complicated. The basis for our chosen hierarchy T(t\th\d)< P(p\ph\b) < K(k\kh\g) может служить наличие simple words type: other Greek (;\;\;;;\;), which in the classical period of the ancient Greek language remained a purely functional word (preserved only in the name of the letter;) or in Lat. (pr\o\mpt\o) – distribute as echoes of a more ancient state of the specified structure of the archaic proto-language. In the work of I. Hajnal \VYa.1992, No. 2\ an interesting analysis of I.-E. is given. consonantism based on the Proto-Ancient Greek, Mycenaean language and indicates the important role of the non-Indo-European substrate in this period. A significant role was played by borrowings from the Bak and Afroasiatic languages, from where consonantal biphonemes of the type -(;;) may have come. Perhaps this is where the unusual consonantal structure of the Greek lambda comes from. This once again emphasizes the possible randomness of such consonantal structures (db) in the initial part \or (bd) in the final part\ i.-e. syllable, but the author still seems to think that their existence is not accidental. These very rare consonantal forms in Slavic languages have been preserved in Russian: (l\a\pt\a), (tpr\u)!, (l\a\pht\ak) - seal skin (arch.). In Sanskrit, similar consonant complexes are found to a greater extent. Thus, in the Sanskrit dictionary you can find at least 28 words with complexes like (..\..\..bd..) in the final part of the words: (st\a\bdh\a), (z\a\bd\a ), (l\u\pt\a), (t\A\pt\i), (st\a\bdh\a), (g\u\ptR), (l\a\bdh\a)… The last word is very similar to Russian (l\a\pt\a). But consonants in the final part of a syllable have reverse order(inverse) compared to the order at the beginning of a syllable. That is, the examples given confirm our assumption that in the earliest period of community, before division, in the phonetic system of I.-e. proto-language there was a hierarchy of articulatory features of type T

In many ways, the first shifts of consonants can be associated precisely with a change in the methods of articulation and a shift to the first positions of labial ones (instead of dental ones), i.e. hierarchy T

English also has many traces of this archaic consonantal system, with dentals being more pronounced than labials (i.e., T precedes P). This is also manifested in the system of sonants, where the basic order is y

It is possible to trace the transformation of the original (b) in various areas (Eastern European and Western European, where its deafening and transformation into the fricative b;p;f is observed):

аblъko (Prussian) ;woble (Prussian)

(I.-e.) *abl-u applu\apful (common German)

abella(Latin\Greek)

In general, this fundamental issue requires a more detailed and in-depth study, but here we will limit ourselves to the above considerations.

In the Introduction it was already emphasized that in preschool children the main core of words (up to 1800) is formed, which includes up to 30% of word forms with a double structure of consonant biphonemes. At the same age, the basic proto-foundation of the phonetic structure of the language being mastered, its condensed scheme, the paradigm of its consonantism and vocalism are also acquired. The basic consonantal paradigm of children's speech is formed mainly between the ages of 2 and 3 years and is determined by the establishment of a distinctive hierarchy based on the “place of formation” feature in the stop subsystem. By this time, he already clearly distinguishes phonemes based on the “method of formation”, distinguishing vowels from sonorants and begins to distinguish stops from the stream of sound forms. In modern children \92, p. 156\ the order P is built in the structure of the word

In classical Latin and ancient Greek, combinations of bd and pt are also observed in the initial consonantal part of syllables: (bd\e\ll\iu\m), (pt\o\s\e), (pt\i\san), (phth \ia), (phth\i\sis), the suffix -\pte\- in Latin - as a reflection of the hardened and already out of use consonantal form. The stable core of monosyllables with the same combination in ancient Greek: (;;\;;\;;); (;;\;;;); (;;\;;); (;;\;;).

It should be noted right away that these are not the only versions for I.-E. consonantism. Since the main goal of our work is to obtain the general metastructure of the phonetic system, we must assume the existence in the archaic period of aspirated voiced sounds (instead of aspirated voiced ones) or guttural models of two aspirates (voiced and voiceless) and a simple voiceless sound, indicated above \ see. T. Gamkrelidze, V. Ivanov, 2\. In such models, slightly different consonant orders are built in correlation triads. This is due to the fact that aspiration (and vocalization) increases the duration (and at the same time narrows the frequency range) of any sound impulse. This gives rise to a hierarchical order in correlated consonantal triads.

In models with a voiced aspirate, this gives the sequence

B) tt< td < tdh; tp < tb < tbh; tk < tg < tgh;

Tt< Tp < Tk;

In guttural models with two types of aspirates, a slightly different hierarchy of differential features is built for phonemes:

C) tt< tth < tdh; tp < tph < tbh; tk < tkh < tgh;

Tt< Tp < Tk;

These variants give rise to the following admissible cluster correlates B) and C) for the stop core of the protolanguage:

The phonological hierarchy of consonants is represented by the chain P

In the general formula of sonorant phonemes R of the proto-language (n\m\;), (l\R\r), (…\i\u) in Fig. 4.b in the main triad of distinctive features of sonorants (nasal\ smooth-laryngeal-quivering \ semiconsonants) the same features are used as secondary features as in the systematization of stop oral phonemes - additional distinctive features according to the method of articulation (labial\ palatal\ dental). A more detailed structure of sonorants (tertiary level structures), taking into account differences in (voicelessness/ringing/aspiration) in sonorants will be given below.

In contrast to the classical method of systematizing phonemes according to characteristics \2-11\, we immediately abandoned the square tables used in traditional approaches and consider language as a continuously changing, dynamic structure in which all its parts interact dialectically (both within individual phonetic, morphological , syntactic subsystems, and the influence of these subsystems on each other). On the other hand, square tables are mainly suitable only for systematizing static systems of binary oppositions such as branching trees, etc. Circular (spiral-sector) tables of the triad type, proposed in this work, make it possible to introduce an element of minimal cyclization, periodic return to the original state (in the language of functional systems - introduce feedback), i.e. take into account the dynamics, evolution, genesis for the hierarchical self-correcting system \1\, to which both the phonetic systems of languages and all other linguistic structures belong.

The proposed method of oriented triads allows you to use the properties and features of the language being studied when analyzing its own structures. Thus, when analyzing the Slavic, Germanic, Latin, Greek languages, you can use (as a preliminary hint) the linguistic category of gender, which immediately gives a triple opposition \cm. Fig. 1\ according to characteristics (male\female\average) and at all its linguistic levels (including phonemic). For example, above we are faced with a triple opposition (ringing\dull\aspiration) or an articulatory triad (dental\labial\palatal (posterior lingual)). In many cases, this turns out to be enough - the language itself, in the process of self-development, has already carried out a certain internal systematization. The principles of systematization used at higher levels of the language are tested at lower levels of its structure, which is revealed with a consistent dialectical approach. The ultimate goal of such an analysis remains to clarify the causes and nature of the internal self-organization that took place in this language. In other languages (French, English, etc.) such a hint does not work, but here the comparative typological and etymological aspects of language research appear.

On the contrary, during typological research they try to find variants of a universal standard language, a metalanguage - a model for a given family of languages - its structure and the implementation as close as possible to it (one of the really existing languages); to reveal through it the universal human universals of thinking and the specific features of specific languages of the entire family.

In the above formula for the correlation series of stop consonants of the Indo-European proto-language, we must also include fricative (whistle/hissing, fricative) consonants, which also appear in correlated groups that are formed at the boundaries (in the transition zones of triads) of the above areas of articulation. In the sequential method of oriented triads, the slots form the next ordered group of wide-range impulses after the stops. According to the same work by Bortko \52\, the duration of fricative impulses is on average shorter than that of stops. But the basis for identifying this group of sounds is a large admixture of hissing and whistling noises, which sharply shifts the frequency maximum to the high-frequency region.

From this point of view, affricates are secondary to stops and sibilants. In the process of continuous reduction, sibilant noisy fricatives fill the central region of fricatives, while affricates and sibilants move into the peripheral sectors of the fricative subsystem.

According to \31\, the fricative phonemes of the proto-language include the anterior lingual sibilant S\Z, the laryngeal posterior lingual aspirate H and several affricates (Aff.). The general fricative system of the proto-language comprised a mega-triad (S\Aff\H). It should be noted that the simple archaic phonetic system of fricatives was transformed (from interaction with stops and semi-consonants) in various dialects into complex subsystems of fricatives and affricates, largely repeating the structure of the original stops. In fact, fricative consonants form a different system of phonemes, orthogonal to stops and sonorants, with a similar structure of oriented triadic complexes of features (clusters). But this is a later stage in the development of language.

Thus, the primary reconstruction of the general phonemic structure of the Indo-European proto-language, taking into account the formulas in Fig. 3 - Fig. 4 and the comments made above, is as follows:

Fig.5. Preliminary reconstruction of the final (presyllabic) stage of the phonetic structure of i.-e. Proto-language.

In the proposed structural formula, C is the subsystem of initial consonants i.-e. syllable; C* – subsystem of final consonants (for example: softened consonants C’* in Slavic languages or deafened in German); V (or g) is a vocal subsystem, the core of which in the present case clearly includes only vowels. This subsystem also includes syllabic sonants Rv, which occupy a middle position between non-syllabic vowels and sonant R (adjacent to semivowels).

The core of the entire phonological structure is a cluster of a group of noisy stop consonants T*, correlated by two types of features (by 2 triads of features of different levels of hierarchy). Fricatives Cs, fricative affricates Af act as transitional phonemes to whistling S (s\z), and sonorant R* are transitional from stops to the vocal subsystem V (syllabic sonants, non-syllabic vowels - short and long). In the pre-archaic period, the formation of language proceeded from the emphasis on vowels and sonorants to stops and sibilants. During the archaic period and after it, this entire metastructure was transformed, forming a more symmetrical phonological structure, evenly filling all its substructures.

In the proto-language there may have been only one vowel (E), which, when interacted with laryngeals (H), produced a basic triad of vowels \31\, both short (a\e\o) and long (a:\e:\o :). Diphthongs of the archaic period, formed by vowels and semi-consonants (i\u\...), formed two series of phonemes (ie\ia\io), (ue\ua\uo) and also constituted a necessary element of i.e. vocalism, occupying an average position in frequency and length of sound between sonorant R (semi-consonants) and vowels r.

On average, vowels and syllabic sonorants occupied the low-frequency acoustic range. This was followed by semivowels and sonorants (quavering/smooth and nasal). The autonomous subsystem of stop consonants occupied a higher frequency range, followed by fricatives (affricates Af and sibilants S). It is in the reverse order that the sectors are filled in the above formula of the phonetic system of the proto-language in Fig. 5, where the direction indicates the bypass of the phonemic structure with a decrease in frequency characteristics (and an increase in the duration of sound impulses timp., updating the phonemes of sounds).

The structural formula of nuclear i.e. discussed above in Fig. 5 phonemes of the proto-language does not yet take into account peripheral phonemes, such as intermediate stop-semi-consonants labialized back-language (Ku\Guh\Gu) \2,31\. A trace of such phonemes remains, for example, in Latin and in modern French, where the phoneme q exists: (Ku, Gu;q). In classical Latin, in addition to the indicated phoneme, there was also the phoneme g;: (Gu;g;). In ancient Greek, the labialized Gu gave the phoneme;: (Gu;;). In the Proto-Slavic language, this series of labialized noisy stops was partially transformed into affricates (Ku;ch,ts\ Gu;zh,z). Thus, the position of this series of labialized stops can be established unambiguously: between the stops of the consonantal nucleus (T) and the sonorants (R). We can safely designate this subsystem of phonemes as Tu (or in a more general form, taking into account possible biphonemes of stops and sonorants, Tr). The echo of such biphonemes is perhaps the nasal sonorant; in French (written gn, softened n: ь): (Gn; ;). The phenomena of this series include the possible formation of click occlusive-nasal affricates (according to the terminology of M. Panov \20\) of the type (pm\tn), or the separation in the phonemic structure of the language of plosive-lateral affricates (biphonemes) of the type (tl \dl).

Thus, a wider selection of consonant phonemes of the archaic period suggests the possibility of including in their system, in addition to stop consonants, still labialized (Tr) and palatal (T0), which can occupy a position between stops (T) and sonorant (R) (or africates Af ).

Such. labiovelar postopalatals delabialized and merged with Proto-Slavic satem postopalatines (k;, g;); (k,g): g;hrno (I.-e); gъrnъ (Proto-Slav.).

On the other hand, in the formula in Fig. 5 we have already included, as an independent subsystem of phonemes, syllabic sonorants (Rv\R*v), such as (re\la\\er\al) and nasal vowels, such as (an\am\en \em), as well as diphthongs and polyphthongs formed by combinations of semi-consonants and vowels like (ja\ ju\ wo). We have already noted above that such phonemes (syllabic) should occupy an intermediate position between sonorant (R) and non-syllabic vowels (v). Let us recall that sonorants (R) include both nasals (n\m\...), smooth ones (l\...\r) and semi-consonants (...\i\u).

The problem of reconstruction of the occipital

- At the dawn of Indo-European studies, relying mainly on data from Sanskrit, scientists reconstructed a four-row system of stop consonants for the Proto-Indo-European language:

This scheme was followed by K. Brugman, A. Leskin, A. Meie, O. Semerenyi, G.A. Ilyinsky, F.F. Fortunatov.

- Later, when it became obvious that Sanskrit was not equivalent to the proto-language, suspicions arose that this reconstruction was unreliable. Indeed, there were quite a few examples that made it possible to reconstruct a series of voiceless aspirates. Some of them were of onomatopoeic origin. The remaining cases, after F. de Saussure put forward the laryngeal theory, brilliantly confirmed after the discovery of the Hittite language, were explained as reflexes of combinations of voiceless stop + laryngeal.

Then the stop system was reinterpreted:

- But this reconstruction also had drawbacks. The first drawback was that the reconstruction of a series of voiced aspirates in the absence of a series of voiceless aspirates is typologically unreliable. The second drawback was that in Proto-Indo-European b there were only three rather unreliable examples. This reconstruction could not explain this fact.

A new stage was the nomination in 1972 of T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov's glottal theory (and independently of them by P. Hopper in 1973). This scheme was based on the shortcomings of the previous one:

This theory allowed for a different interpretation of the laws of Grassmann and Bartholomew, and also gave a new meaning to Grimm’s law. However, this scheme also seemed imperfect to many scientists. In particular, it suggests for the late Proto-Indo-European period the transition of glottalized consonants to voiced ones, despite the fact that glottalized ones are rather unvoiced sounds.

- The latest reinterpretation was made by V.V. Shevoroshkin, who suggested that Proto-Indo-European did not have glottalized ones, but “strong” stops, which are found in some Caucasian languages. This type of stop can actually be voiced.

The problem of the number of guttural rows

If the reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European language were based solely on data from the Indo-Iranian, Baltic, Slavic, Armenian and Albanian languages, then it would be necessary to admit that in Proto-Indo-European there were two series of gutturals - simple and palatalized.

But if the reconstruction were based on data from the Celtic, Italic, Germanic, Tocharian and Greek languages, then the other two series would have to be accepted - guttural simple and labialized.

The languages of the first group (Satem) do not have labializations, and the languages of the second group (Centum) do not have palatalizations. Accordingly, a compromise in this situation is to accept three series of gutturals for the Proto-Indo-European language (simple, palatalized and labialized). However, such a concept runs into a typological argument: there are no living languages in which such a guttural system would exist.

There is a theory that suggests that the situation in the Centum languages is primordial, and the Satem languages palatalized the old simple guttural ones, while the old labialized ones changed into simple ones.

The opposite hypothesis to the previous one states that in Proto-Indo-European there were simple guttural and palatalized ones. At the same time, in Centum languages, simple ones became labialized, and palatalized ones became depalatalized.

And finally, there are supporters of the theory according to which in Proto-Indo-European there was only one series of gutturals - simple.

Problems of reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European spirants

It is traditionally believed that Proto-Indo-European had only one spirant s, the allophone of which in position before voiced consonants was z. Three different attempts were made by different linguists to increase the number of spirants in the reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European language:

- The first attempt was made by Karl Brugman. See Brugman's article Spiranta.

- The second was undertaken by E. Benveniste. He attempted to assign an affricate c to the Indo-European language. The attempt was unsuccessful.

- T.V. Gamkrelidze and V.V. Ivanov, based on a small number of examples, postulated a series of spirants for Proto-Indo-European: s - s" - s w.

The problem of the number of laryngeal

The laryngeal theory in its original form was put forward by F. de Saussure in his work “Article on the original vowel system in Indo-European languages.” F. de Saussure blamed some alternations in Sanskrit suffixes on a certain “sonantic coefficient” unknown to any living Indo-European language. After the discovery and decipherment of the Hittite language, Jerzy Kurylowicz identified the “sonantic coefficient” with the laryngeal phoneme of the Hittite language, since in the Hittite language this laryngal was exactly where the “sonantic coefficient” was located according to Saussure. It was also found that the laryngals, being lost, actively influenced the quantity and quality of neighboring Proto-Indo-European vowels. However, at the moment there is no consensus among scientists regarding the number of laryngeals in Proto-Indo-European. The estimates vary over a very wide range - from one to ten.

Traditional reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European phonetics

| Labial | Dental | Guttural | Laryngals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| palatal | velar | labio-velar | |||||

| Nasals | m | n | |||||

| Occlusive | p | t | ḱ | k | kʷ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ǵ | g | gʷ | ||

| voiced aspirates | bʰ | dʰ | ǵʰ | gʰ | gʷʰ | ||

| Fricatives | s | h₁, h₂, h₃ | |||||

| Smooth | r, l | ||||||

| Semivowels | j | w | |||||

- Short vowels a, e, i, o, u

- Long vowels ā, ē, ō, ī, ū .

- Diphthongs ai, au, āi, āu, ei, eu, ēi, ēu, oi, ou, ōi, ōu

- Vowel allophones of sonants: u, i, r̥, l̥, m̥, n̥.

Grammar

Language structure

Almost all modern and known ancient Indo-European languages are nominative languages. However, many experts hypothesize that the Proto-Indo-European language in the early stages of its development was an active language; Subsequently, the names of the active class became masculine and feminine, and those of the inactive class became neuter. This is evidenced, in particular, by the complete coincidence of the forms of the nominative and accusative cases of the neuter gender. The division of nouns in the Russian language into animate and inanimate (with the coincidence of the nominative and accusative case of inanimate nouns in many forms) is also perhaps a distant reflex of the active structure. To the greatest extent, remnants of the active system have been preserved in the Aryan languages; in other Indo-European languages, the division into active and passive is rigid. Constructions resembling active construction in modern English (he sells a book - he sells a book, but a book sells at $20 - a book is sold for 20 dollars) are secondary and not directly inherited from Proto-Indo-European.

Noun

Nouns in Proto-Indo-European had eight cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental, disjunctive, locative, vocative; three grammatical numbers: singular, dual and plural. It was generally believed that there were three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. However, the discovery of the Hittite language, in which there are only two genders ("general" or "animate") and neuter, cast doubt on this. Various hypotheses have been put forward about when and how the feminine gender appeared in Indo-European languages.

Table of noun endings:

| (Beeks 1995) | (Ramat 1998) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athematic | Thematic | ||||||||||||||

| Male and female | Average | Male and female | Average | Male | Average | ||||||||||

| Unit | Plural | Two. | Unit | Plural | Two. | Unit | Plural | Two. | Unit | Plural | Unit | Plural | Two. | Unit | |

| Nominative | -s,0 | -es | -h 1 (e) | -m,0 | -h 2 , 0 | -ih 1 | -s | -es | -h 1 e? | 0 | (coll.) -(e)h 2 | -os | -ōs | -oh 1 (u)? | -om |

| Accusative | -m | -ns | -ih 1 | -m,0 | -h 2 , 0 | -ih 1 | -m̥ | -ms | -h 1 e? | 0 | -om | -ons | -oh 1 (u)? | -om | |

| Genitive | -(o)s | -om | -h 1 e | -(o)s | -om | -h 1 e | -es, -os, -s | -ōm | -os(y)o | -ōm | |||||

| Dative | -(e)i | -mus | -me | -(e)i | -mus | -me | -ei | -ōi | |||||||

| Instrumental | -(e)h 1 | -bʰi | -bʰih 1 | -(e)h 1 | -bʰi | -bʰih 1 | -bʰi | -ō | -ōjs | ||||||

| Separate | -(o)s | -ios | -ios | -(o)s | -ios | -ios | |||||||||

| Local | -i, 0 | -su | -h 1 ou | -i, 0 | -su | -h 1 ou | -i, 0 | -su, -si | -oj | -ojsu, -ojsi | |||||

| Vocative | 0 | -es | -h 1 (e) | -m,0 | -h 2 , 0 | -ih 1 | -es | (coll.) -(e)h 2 | |||||||

Pronoun

Table of declension of personal pronouns:

| Personal pronouns (Beekes 1995) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First person | Second person | |||

| Unity | Multiply | Unity | Multiply | |

| Nominative | h 1 eǵ(oH/Hom) | uei | tuH | iuH |

| Accusative | h 1 mé, h 1 me | nsmé, nōs | tué | usme, wōs |

| Genitive | h 1 mene, h 1 moi | ns(er)o-, nos | teue, toi | ius(er)o-, wos |

| Dative | h 1 méǵʰio, h 1 moi | nsmei, ns | tébʰio, toi | usmei |

| Instrumental | h 1 moi | ? | toí | ? |

| Separate | h 1 med | nsmed | tuned | usmed |

| Local | h 1 moi | nsmi | toí | usmi |

The 1st and 2nd person pronouns did not differ in gender (this feature is preserved in all other Indo-European languages). Personal pronouns of the 3rd person were absent in the Proto-Indo-European language and various demonstrative pronouns were used instead.

Verb

Table of verb endings:

| Buck 1933 | Beekes 1995 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athematic | Thematic | Athematic | Thematic | ||

| Unity | 1st | -mi | -ō | -mi | -oH |

| 2nd | -si | -esi | -si | -eh₁i | |

| 3rd | -ti | -eti | -ti | -e | |

| Multiply | 1st | -mos/mes | -omos/omes | -mes | -omom |

| 2nd | -te | -ete | -th₁e | -eth₁e | |

| 3rd | -nti | -onti | -nti | -o | |

Numerals

Some cardinal numbers (masculine) are listed below:

| Sihler | Beekes | |

|---|---|---|

| one | *Hoi-no-/*Hoi-wo-/*Hoi-k(ʷ)o-; *sem- | *Hoi(H)nos |

| two | *d(u)wo- | *duoh₁ |

| three | *trei- / *tri- | *trees |

| four | *kʷetwor-

/ *kʷetur-

(see also en:kʷetwóres rule) |

*kʷetuōr |

| five | *penkʷe | *penkʷe |

| six | *s(w)eḱs ; initially, perhaps *weḱs | *(s)uéks |

| seven | *septm | *septm |

| eight | *oḱtō , *oḱtou or *h₃eḱtō , *h₃eḱtou | *h₃eḱteh₃ |

| nine | *(h₁)newn̥ | *(h₁)neun |

| ten | *deḱm̥(t) | *déḱmt |

| twenty | *wīḱm̥t- ; initially, perhaps *widḱomt- | *duidḱmti |

| thirty | *trīḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *tridḱomt- | *trih₂dḱomth₂ |

| fourty | *kʷetwr̥̄ḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *kʷetwr̥dḱomt- | *kʷeturdḱomth₂ |

| fifty | *penkʷēḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *penkʷedḱomt- | *penkʷedḱomth₂ |

| sixty | *s(w)eḱsḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *weḱsdḱomt- | *ueksdḱomth₂ |

| seventy | *septm̥̄ḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *septmdḱomt- | *septmdḱomth₂ |

| eighty | *oḱtō(u)ḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *h₃eḱto(u)dḱomt- | *h₃eḱth₃dḱomth₂ |

| ninety | *(h₁)newn̥̄ḱomt- ; initially, perhaps *h₁newn̥dḱomt- | *h₁neundḱomth₂ |

| one hundred | *ḱmtom ; initially, perhaps *dḱmtom | *dḱmtom |

| thousand | *ǵheslo- ; *tusdḱomti | *ǵʰes-l- |

Examples of texts

Attention! These examples are written in a form adapted to the standard Latin alphabet and reflect only one of the reconstruction options. Translations of texts are largely speculative, are of no interest to specialists and do not reflect the subtleties of pronunciation. They are placed here solely for demonstration and to get an initial idea of the language.

Ovis ecvosque (Sheep and horse)

(Schleicher's Tale)

Gorei ovis, quesuo vlana ne est, ecvons especet, oinom ghe guerom voghom veghontum, oinomque megam bhorom, oinomque ghmenum ocu bherontum. Ovis nu ecvobhos eveghuet: "Cer aghnutoi moi, ecvons agontum manum, nerm videntei." Ecvos to evequont: “Cludhi, ovei, cer ghe aghnutoi nasmei videntibhos: ner, potis, oviom egh vulnem sebhi nevo ghuermom vestrom cvergneti; neghi oviom vulne esti.” Tod cecleus ovis agrom ebheguet.

- Approximate translation:

On the mountain, a sheep that had no wool saw horses: one was carrying a heavy cart, one was carrying a large load, one was quickly carrying a man. The sheep says to the horses: “My heart burns when I see horses carrying people, men.” The horse replies: “Listen, sheep, our hearts also burn when we see a man, a craftsman making new warm clothes for himself from sheep’s wool; and the sheep remains without wool.” Hearing this, the sheep in the field ran away.

Regs deivosque (King and God)

Version 1

Potis ghe est. Soque negenetos est. Sunumque evelt. So gheuterem precet: “Sunus moi gueniotam!” Gheuter nu potim veghuet: “Iecesuo ghi deivom Verunom.” Upo pro potisque deivom sesore deivomque iecto. "Cludhi moi, deive Verune!" So nu cata divos guomt. “Quid velsi?” "Velnemi sunum." "Tod estu", vequet leucos deivos. Potenia ghi sunum gegone.

Version 2

To regs est. So nepotlus est. So regs sunum evelt. So tosuo gheuterem precet: “Sunus moi gueniotam!” So gheuter tom reguem eveghuet: “Iecesuo deivom Verunom.” So regs deivom Verunom upo sesore nu deivom iecto. "Cludhi moi, pater Verune!" Deivos verunos cata divos eguomt. “Quid velsi?” "Velmi sunum." "Tod estu", veghuet leucos deivos Verunos. Regos potenia sunum gegone.

- Approximate translation:

Once upon a time there lived a king. But he was childless. And the king wanted a son. And he asked the priest: “I want a son to be born to me!” The priest answers that king: “Turn to the god Varuna.” And the king came to the god Varuna to make a request to him. “Listen to me, Varun’s father!” God Varuna descended from heaven. "What you want?" “I want a son.” “So be it,” said the radiant god Varuna. The king's wife gave birth to a son.

Pater naseros

Version 1

Pater naseros cemeni, nomen tovos estu cventos, reguom tevem guemoit ad nas, veltos tevem cvergeto cemeni ertique, edom naserom agheres do nasmebhos aghei tosmei le todque agosnes nasera, so lemos scelobhos naserobhos. Neque peretod nas, tou tratod nas apo peuces. Teve senti reguom, maghti decoromque bhegh antom. Estod.

Version 2

Pater naseros cemeni, nomen tovos estu iseros, reguom tevem guemoit ad nasmens, ghuelonom tevom cvergeto cemeni ed eri, edom naserom agheres do nasmebhos tosmei aghei ed le agosnes nasera, so lemos scelobhos naserobhos. Neque gvedhe nasmens bhi perendom, tou bhegue nasmens melguod. Teve senti reguom, maghti ed decorom eneu antom. Estod.

- Approximate translation:

Our heavenly Father, hallowed be your name, may your kingdom come over us, your will be done in heaven and on earth, give us our daily food this day, and forgive our debts, as we forgive our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Yours is the kingdom, the power and the glory without end. Amen.

Aquan Nepot

Puros esiem. Deivons aisiem. Aquan Nepot dverbhos me rues! Meg moris me gherdmi. Deivos, tebherm gheumi. Vicpoteis tebherm gheumi. Ansues tebherm guemi. Nasmei guertins dedemi! Ad bherome deivobhos ci sime guerenti! Dotores vesvom, nas nasmei creddhemes. Aquan Nepot, dverons sceledhi! Dghom Mater toi gheumes! Dghemia Mater, tebhiom gheumes! Meg moris nas gherdmi. Eghuies, nasmei sercemes.

- Approximate translation:

Cleaning myself up. I worship the gods. Son of Water, open the doors for me! The big sea surrounds me. I make offerings to the gods. I make offerings to my ancestors. I make offerings to the spirits. Thank you! We are here to honor the gods. Donors to the gods, we have dedicated our hearts to you. Son of Water, open the doors for us! Mother of the Earth, we worship you! We make offerings to you! We are surrounded by a large sea. (...)

Marie

Decta esies, Mari plena gusteis, arios com tvoio esti, guerta enter guenai ed guertos ogos esti tovi bhermi, Iese. Isere Mari, deivosuo mater, meldhe nobhei agosorbhos nu dictique naseri merti. Estod.

- Approximate translation:

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with you, blessed among women and blessed is the Fruit of your womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Amen.

Creddheo

Creddheo deivom, paterom duom dheterom cemenes ertique, Iesom Christomque sunum sovom pregenetom, ariom naserom. Ansus iserod tectom guenios Mariam genetom. (...) ad lendhem mertvos, vitero genetom agheni tritoi necubhos, uposteightom en cemenem. Sedeti decsteroi deivosuo pateronos. Creddheo ansum iserom, eclesiam catholicam iseram, (…) iserom, (…) agosom ed guivum eneu antom. Decos esiet patorei sunumque ansumque iseroi, agroi ed nu, ed eneu antom ad aivumque. Estod.

- Approximate translation:

I believe in God, the Almighty Father, creator of heaven and earth, and Jesus Christ, his own Son, our Lord. By the conception of the Holy Spirit the Virgin Mary was born. (...) to the ground dead, and resurrected on the third day after death, ascended into heaven, sat down to the right of God his Father. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy Catholic Church, (...) saints, (the remission of) sins and life without end. Glory to the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit equally, now and without end and forever. Amen

Dictionary of linguistic terms

INDO-EUROPEAN, oh, oh. 1. see Indo-Europeans. 2. Relating to the Indo-Europeans, their origin, languages, national character, way of life, culture, as well as the territories and places of their residence, their internal structure, history; such,… … Ozhegov's Explanatory Dictionary

Parent language- (base language) a language from the dialects of which a group of related languages originated, otherwise called a family (see Genealogical classification of languages). From the point of view of the formal apparatus of comparative historical linguistics, each unit of the proto-language... Linguistic encyclopedic dictionary

The I. proto-language in the era before its division into separate I. languages had the following consonant sounds. A. Explosive, or explosive. Labials: voiceless p and voiced b; anterior lingual teeth: voiceless t and voiced d; posterior lingual anterior and palatal: deaf. k1 and... ...

Basic language, protolanguage, term denoting the hypothetical state of a group or family of related languages, reconstructed on the basis of a system of correspondences that are established between languages in the field of phonetics, grammar and semantics... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

In the era before its division into separate languages, the I. proto-language had the following vowel sounds: i î, and û, e ê, o ô, a â, and an indefinite vowel. In addition, in known cases, the role of vowel sounds was played by smooth consonants r, l and nasal n, t... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Ephron

Aya, oh. ◊ Indo-European languages. Linguistic The general name for a large group of modern and ancient related languages of Asia and Europe, to which belong the languages Indian, Iranian, Greek, Slavic, Baltic, Germanic, Celtic, Romance and... encyclopedic Dictionary

proto-language- The common ancestor of these languages discovered through the comparative study of related languages (see Relatedness of languages). These are, for example, P. common Slavic, or Proto-Slavic, from which all Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Serbian, etc.) originated... ... Grammar Dictionary: Grammar and linguistic terms

Preface from the journal “Science and Life” No. 12, 1992:

Now we have become accustomed to the truth that the path of humanity, its awareness of itself and the world around it from the point of view of eternity, does not have such a long history. Much remains to be learned, discovered, and seen in a new way. And yet, you must admit, now, at the end of the 20th century, it’s not even easy to believe in major discoveries: in the philistine way, somewhere deep down in our souls we believe that everything that can surprise us has already surprised us.

The joint work of Academician Tamaz Valerianovich Gamkrelidze and Doctor of Philology Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov, “Indo-European Language and Indo-Europeans,” published in two volumes in Tbilisi in 1984, became the subject of lively discussions among professional colleagues: loud praise and sharp criticism.

In an extremely condensed form, the idea of the new hypothesis put forward by linguists is as follows: the homeland of the Indo-Europeans is Western Asia, the time of formation is the turn of the V-IV millennium. (In fact, this is not a new hypothesis, but an attempt, taking into account new historical and linguistic material, to patch up Marr’s old theory about the Caucasian cradle of human culture, the Middle Eastern cradle of writing and the late origin of the Slavic group of languages. This tendency is felt even in the drawing of the tree of languages in the article Gamkrelidze - drawing Slavic dialects at the beginning of the tree, which corresponds to new data, the authors do not link them to the trunk, which allows them to leave late dates for the appearance of Slavic languages, previously derived from Lithuanian (Balto-Slavic) - L.P.)

This fundamental work (it contains more than a thousand pages) forces us to take a fresh look at the prevailing scientific ideas about the proto-language and protoculture of the Indo-Europeans, about the localization of the place of their origin. The Near Asian theory of the origin of the Indo-Europeans makes it possible to “draw” a new picture of their settlement and migrations. The authors of the new theory do not at all claim to have absolute truth. But if it is accepted, then all the previously assumed trajectories of prehistoric migrations of speakers of ancient European dialects, the panorama of the origin and prehistory of European peoples will radically change. If we recognize Western Asia as the most ancient center of human civilization, from where the cultural achievements of mankind advanced in different ways to the west and east, then, accordingly, the west and east of Eurasia will also be perceived in a new way: not as (or not only as) a gigantic accumulation of diverse dialects, traditions, cultures , but in a certain sense as a single cultural area on the territory of which modern human civilization arose and developed. Today, something else is obvious - joint efforts of various sciences are necessary in studying the history of the Indo-Europeans.

Linguistics is distinguished by the fact that it has a method that allows one to penetrate deeply into the past of related languages and restore their common source - the proto-language of a family of languages. (This is not true. Modern Indo-European studies did not yet have such methods. For the possibilities of linguistics in this area, see above quotes from the great Meillet. Until now, this, unfortunately, was impossible if we used only the methods of comparative linguistics. - L.R. ) By comparing words and forms that partially coincide in sound and meaning, linguists manage to reconstruct what seems to be gone forever - how a word once sounded, which later received a different pronunciation in each of the related languages.

Indo-European languages are one of the largest linguistic families in Eurasia. Many of the ancient languages of this family have long since disappeared.

Science has been engaged in the reconstruction of the Indo-European proto-language for two centuries, but many unresolved questions remain. Although the classical picture of the Indo-European proto-language had already been created at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries, after previously unknown groups of Indo-European languages were discovered, a rethinking of the entire Indo-European problem was required.

The greatest significance for comparative historical linguistics was the decipherment of cuneiform Hittite tablets carried out by the Czech orientalist B. Grozny during the First World War. (most of the texts of the X-VIII centuries BC, but among them there are also individual tablets of the XIII-XVIII centuries, which are written on the borrowed sign system of Akkadian writing, which indicates that the language of these later texts underwent significant Semitization, and therefore cannot be considered the proto-language of the local proto-culture - L.R.) from the ancient capital of the Hittite kingdom Hattusas (200 km from Ankara). In the summer of 1987, the authors of the article were lucky enough to visit the excavations of Hattusas (they were led by an expedition of the German Archaeological Institute). Researchers have truly discovered a whole library of cuneiform documents; in it, in addition to Hittite texts, cuneiform tablets in other Ancient Indo-European languages - Palaic and Luwian - have been discovered. (Palaian and Luwian dialects of Hittite contain only a layer of Indo-European vocabulary, and therefore also bear traces of the conquering transformation - L.R.). Close to the language of the Luwian cuneiform tablets is the deciphered language of the Luwian hieroglyphic inscriptions of Asia Minor and Syria, most of which were compiled after the collapse of the Hittite Empire (after 1200 BC). The continuation of Luwian turned out to be the Lycian language, which has long been known from inscriptions made in the west of Asia Minor - in Lycia in ancient times. Thus, science included two groups of Indo-European languages of ancient Anatolia - Hittite and Luwian.

Another group, the Tocharian, was discovered thanks to discoveries made by scientists from different countries in Chinese (East) Turkestan at the end of the 19th century. Tocharian texts were written in one of the variants of the Indian Brahmi script in the 2nd half of the 1st millennium AD. e. and were translations of Buddhist works, which greatly facilitated their decipherment.

As previously unknown Indo-European languages were studied, it became possible to verify (as experts in the logic of science say, “falsify”) previously made conclusions about the ancient appearance of the dialects of the Indo-European proto-language. Based on new methods of linguistics, possible structural types of languages have been studied, and some general principles found in all languages of the world have been established.

And yet unresolved questions remain. There seemed to be no reason to think that the Indo-European proto-language differed in structure from all the languages already known to us. But at the same time, how to explain, for example, this: in the Indo-European proto-language there is no one consonant characterized by the participation of the lips in its pronunciation (it’s very easy to explain: by this late time, which is being studied, the language, which has only a residual Indo-European layer of vocabulary, had already lost its native labial sounds as a result of the introduction of foreign writing by the conquerors, as a result of which it would be more correct to write that in the “Hittite language did not find one consonant characterized by the participation of the lips in its pronunciation,” while this same idea in relation to the proto-language is essentially a stretch - L.R.). The previous comparative grammar assumed that this sound, as it were, missing in the system (or extremely rare) could be characterized as Russian b. However, the structural typology of the world's languages makes such an assumption extremely unlikely: if a language lacks one of the labial sounds like b or p, then it is least likely that this sound is voiced, like b in Russian. From the revision of the characteristics of this sound followed a whole series of new assumptions regarding the entire consonant system of the Indo-European proto-language.

The hypothesis we put forward on this issue back in 1972, as well as similar assumptions of other scientists, is currently being vigorously discussed. Broader conclusions regarding the typological similarity of the ancient Indo-European language with other neighboring languages depend on the final resolution of the issue.

The results of the study of these and other problems were reflected in our two-volume study “Indo-European Language and Indo-Europeans” (Tbilisi, 1984). The first volume examines the structure of the proto-language of this family: its sound system, vowel alternations, root structure, the most ancient grammatical categories of noun and verb, ways of expressing them, the order of grammatical elements in a sentence, dialect division of the Indo-European language region. But the created dictionary of the Indo-European proto-language (it is published in the second volume) makes it possible to reconstruct the ancient culture of those who spoke this language.