One of the epoch-making events in the history of modern paints is the world-famous invention - Prussian blue. Today the year of manufacture is considered to be 1704, and the inventor is the dyer from Berlin Biesbach. Its discovery made it possible to obtain a truly rich and expressive blue color, which, without any doubt, immediately gained great popularity and respect not only among artists, but also among tailors and builders.

With its appearance, Prussian blue provided ample opportunities for various areas of craftsmanship: from furniture manufacturers to architects.

Undoubtedly, the name given to this shade best describes its content. Indeed, in terms of depth of tone, originality, saturation and brightness, it really has a lot in common with azure, but it can be called more calm and balanced. Color truly became the “calling card” of Berlin of its time, which was then distinguished by its cold and gloomy atmosphere in its perfection of images and forms.

It is for sure the brightest shade that would ever be associated with the elite and aristocracy, which is why Prussian blue is the ideal tone for the living room, which takes on a very rich and presentable look with it. Undoubtedly, due to the fact that this paint has a rather restrained brightness, bringing peace, as well as comfort and tranquility, this color will be the best solution for decorating bedrooms, while the severity and sublimity will make the interior of any office or, for example, a library more solid and impressive. As already mentioned, the use of Prussian blue is widely used in construction; today it has become very popular to decorate windows. And this is understandable, because Prussian blue is an excellent paint for glass, and not just for walls or furniture.

It is for sure the brightest shade that would ever be associated with the elite and aristocracy, which is why Prussian blue is the ideal tone for the living room, which takes on a very rich and presentable look with it. Undoubtedly, due to the fact that this paint has a rather restrained brightness, bringing peace, as well as comfort and tranquility, this color will be the best solution for decorating bedrooms, while the severity and sublimity will make the interior of any office or, for example, a library more solid and impressive. As already mentioned, the use of Prussian blue is widely used in construction; today it has become very popular to decorate windows. And this is understandable, because Prussian blue is an excellent paint for glass, and not just for walls or furniture.

Today there are paints that can often be confused with this shade. For example, Turnboole blue. However, it has a number of its own characteristics, which are often significantly different from Prussian blue. Indeed, due to its delicate and unique shades, it harmonizes very well with almost any other shades. A pattern made in the color of green tea or, say, mint against a Prussian blue background can give an incredible freshness to the room. If, to create an interior, it is necessary for it to have a more refined and aristocratic look, it is possible to add soft pink. For a spectacular and catchy interior, add somon, and a lemon-cream tone will allow you to somewhat cool the atmosphere. For emphasis, it is possible to combine with muted pear or coffee-milk colors. Interest is created by bringing combinations with orange, turquoise or aquamarine colors into the interior.

Today there are paints that can often be confused with this shade. For example, Turnboole blue. However, it has a number of its own characteristics, which are often significantly different from Prussian blue. Indeed, due to its delicate and unique shades, it harmonizes very well with almost any other shades. A pattern made in the color of green tea or, say, mint against a Prussian blue background can give an incredible freshness to the room. If, to create an interior, it is necessary for it to have a more refined and aristocratic look, it is possible to add soft pink. For a spectacular and catchy interior, add somon, and a lemon-cream tone will allow you to somewhat cool the atmosphere. For emphasis, it is possible to combine with muted pear or coffee-milk colors. Interest is created by bringing combinations with orange, turquoise or aquamarine colors into the interior.

In general, the shade, once invented in Berlin by the dyer Biesbach, is still a huge success today, because it can radically change the familiar interior and decor of modern times.

¹

: Normalized to

²

: Normalized to

History and origin of the name

The exact date of receipt of Prussian blue is unknown. According to the most common version, it was obtained at the beginning of the eighteenth century (1706) in Berlin by the dyer Diesbach. In some sources he is called Johann Jakob Diesbach (German). Johann Jacob Diesbach) . The intense bright blue color of the compound and the location of its origin give rise to the name. From a modern point of view, the production of Prussian blue consisted of the precipitation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (II) by adding iron (II) salts (for example, “iron sulfate”) to the “yellow blood salt” and subsequent oxidation to iron (II) hexacyanoferrate ( III). It was possible to do without oxidation if iron (III) salts were immediately added to the “yellow blood salt”.

Under the name “Paris blue”, purified “Prussian blue” was at one time proposed.

Receipt

The preparation method was kept secret until the publication of the production method by the Englishman Woodward in 1724.

Prussian blue can be obtained by adding ferric iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) (“yellow blood salt”). In this case, depending on the conditions, the reaction can proceed according to the equations:

Fe III Cl 3 + K 4 → KFe III + 3KCl,

or, in ionic form

Fe 3+ + 4− → Fe −

The resulting potassium iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II) is soluble and is therefore called "soluble Prussian blue".

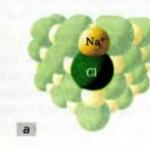

The structural diagram of soluble Prussian blue (crystalline hydrate of the type KFe III ·H 2 O) is shown in the figure. It shows that the Fe 2+ and Fe 3+ atoms are located in the crystal lattice in the same way, but in relation to the cyanide groups they are unequal; the prevailing tendency is to be located between carbon atoms, and Fe 3+ - between nitrogen atoms.

4Fe III Cl 3 + 3K 4 → Fe III 4 3 ↓ + 12KCl,

or, in ionic form

4Fe 3+ + 3 4− → Fe III 4 3 ↓

The resulting insoluble (solubility 2·10−6 mol/l) precipitate of iron (III) hexacyanoferrate (II) is called "insoluble Prussian blue".

The above reactions are used in analytical chemistry to determine the presence of Fe 3+ ions

Another method is to add divalent iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) (“red blood salt”). The reaction also occurs with the formation of soluble and insoluble forms (see above), for example, according to the equation (in ionic form):

4Fe 2+ + 3 3− → Fe III 4 3 ↓

Previously, it was believed that this resulted in the formation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (III), that is, Fe II 3 2, this is exactly the formula proposed for “Turnboole blue”. It is now known (see above) that Turnboole blue and Prussian blue are the same substance, and during the reaction, electrons transfer from Fe 2+ ions to hexacyanoferrate (III) ion (valence rearrangement of Fe 2+ + to Fe 3 + + occurs almost instantly; the reverse reaction can be carried out in a vacuum at 300 °C).

This reaction is also analytical and is used, accordingly, for the determination of Fe 2+ ions.

In the ancient method of producing Prussian blue, when solutions of yellow blood salt and iron sulfate were mixed, the reaction proceeded according to the equation:

Fe II SO 4 + K 4 → K 2 Fe II + K 2 SO 4.

The resulting white precipitate of potassium-iron(II) hexacyanoferrate(II) (Everitt's salt) is quickly oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to potassium-iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II), that is, Prussian blue.

Properties

The thermal decomposition of Prussian blue follows the following schemes:

at 200 °C:

3Fe 4 3 →(t) 6(CN) 2 + 7Fe 2

at 560 °C:

Fe 2 →(t) 3N 2 + Fe 3 C + 5C

An interesting property of the insoluble form of Prussian blue is that, being a semiconductor, when cooled very strongly (below 5.5 K) it becomes a ferromagnet - a unique property among metal coordination compounds.

Application

As a pigment

The color of iron blue changes from dark blue to light blue as the potassium content increases. The intense bright blue color of Prussian blue is probably due to the simultaneous presence of iron in different oxidation states, since the presence of one element in different oxidation states in compounds often gives rise to or intensification of color.

Dark azure is hard, difficult to wet and disperse, glazes in paints and, when floating up, gives a mirror reflection of yellow-red rays (“bronzing”).

Iron glaze, due to its good hiding power and beautiful blue color, is widely used as a pigment for the manufacture of paints and enamels.

It is also used in the production of printing inks, blue carbon paper, and tinting colorless polymers such as polyethylene.

The use of iron glaze is limited by its instability in relation to alkalis, under the influence of which it decomposes with the release of iron hydroxide Fe(OH) 3. It cannot be used in composite materials containing alkaline components, and for painting on lime plaster.

In such materials, the organic pigment phthalocyanine blue is usually used as a blue pigment.

Medicine

Also used as an antidote (Ferrocin tablets) for poisoning with thallium and cesium salts, to bind radioactive nuclides entering the gastrointestinal tract and thereby prevent their absorption. ATX code . The pharmacopoeial drug Ferrocin was approved by the Pharmaceutical Committee and the USSR Ministry of Health in 1978 for use in acute human poisoning with cesium isotopes. Ferrocine consists of 5% potassium iron hexacyanoferrate KFe and 95% iron hexacyanoferrate Fe43.

Veterinary drug

To rehabilitate lands contaminated after the Chernobyl disaster, a veterinary drug was created based on the medical active component Ferrocin-Bifezh. Included in the State Register of Medicines for Veterinary Use under number 46-3-16.12-0827 No. PVR-3-5.5/01571.

Other Applications

Before wet copying of documents and drawings was replaced by dry copying, Prussian blue was the main pigment produced in the process. photocopying(so-called “blueing”, cyanotype process).

In a mixture with oily materials, it is used to control the tightness of surfaces and the quality of their processing. To do this, the surfaces are rubbed with the specified mixture, then combined. Remains of unerased blue mixture indicate deeper places.

Also used as a complexing agent, for example to produce prussids.

In the 19th century, it was used in Russia and China to tint dormant tea leaves, as well as to recolor black tea green.

Toxicity

It is not a toxic substance, although it contains the cyanide anion CN−, since it is firmly bound in the stable complex hexacyanoferrate 4− anion (the instability constant of this anion is only 4·10−36).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

see also

Write a review about the article "Prussian Blue"

Literature

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg. , 1890-1907.

Notes

Links

|

||||||||||

An excerpt characterizing Prussian Blue

Meanwhile, another column was supposed to attack the French from the front, but Kutuzov was with this column. He knew well that nothing but confusion would come out of this battle that had begun against his will, and, as far as it was in his power, he held back the troops. He didn't move.

Kutuzov rode silently on his gray horse, lazily responding to proposals to attack.

“You’re all about attacking, but you don’t see that we don’t know how to do complex maneuvers,” he said to Miloradovich, who asked to go forward.

“They didn’t know how to take Murat alive in the morning and arrive at the place on time: now there’s nothing to do!” - he answered the other.

When Kutuzov was informed that in the rear of the French, where, according to the Cossacks’ reports, there had been no one before, there were now two battalions of Poles, he glanced back at Yermolov (he had not spoken to him since yesterday).

“They ask for an offensive, they propose various projects, but as soon as you get down to business, nothing is ready, and the forewarned enemy takes his own measures.”

Ermolov narrowed his eyes and smiled slightly when he heard these words. He realized that the storm had passed for him and that Kutuzov would limit himself to this hint.

“He’s having fun at my expense,” Ermolov said quietly, nudging Raevsky, who was standing next to him, with his knee.

Soon after this, Ermolov moved forward to Kutuzov and respectfully reported:

- Time has not been lost, your lordship, the enemy has not left. What if you order an attack? Otherwise the guards won’t even see the smoke.

Kutuzov said nothing, but when he was informed that Murat’s troops were retreating, he ordered an offensive; but every hundred steps he stopped for three quarters of an hour.

The whole battle consisted only in what Orlov Denisov’s Cossacks did; the rest of the troops only lost several hundred people in vain.

As a result of this battle, Kutuzov received a diamond badge, Bennigsen also received diamonds and a hundred thousand rubles, others, according to their ranks, also received a lot of pleasant things, and after this battle even new movements were made at headquarters.

“This is how we always do things, everything is topsy-turvy!” - Russian officers and generals said after the Tarutino battle, - exactly the same as they say now, making it feel like someone stupid is doing it this way, inside out, but we wouldn’t do it that way. But people who say this either do not know the matter they are talking about or are deliberately deceiving themselves. Every battle - Tarutino, Borodino, Austerlitz - is not carried out as its managers intended. This is an essential condition.

An innumerable number of free forces (for nowhere is a person freer than during a battle, where it is a matter of life and death) influences the direction of the battle, and this direction can never be known in advance and never coincides with the direction of any one force.

If many, simultaneously and variously directed forces act on some body, then the direction of movement of this body cannot coincide with any of the forces; and there will always be an average, shortest direction, what in mechanics is expressed by the diagonal of a parallelogram of forces.

If in the descriptions of historians, especially French ones, we find that their wars and battles are carried out according to a certain plan in advance, then the only conclusion that we can draw from this is that these descriptions are not true.

The Tarutino battle, obviously, did not achieve the goal that Tol had in mind: in order to bring troops into action according to disposition, and the one that Count Orlov could have had; to capture Murat, or the goals of instantly exterminating the entire corps, which Bennigsen and other persons could have, or the goals of an officer who wanted to get involved and distinguish himself, or a Cossack who wanted to acquire more booty than he acquired, etc. But , if the goal was what actually happened, and what was a common desire for all Russian people then (the expulsion of the French from Russia and the extermination of their army), then it will be completely clear that the Tarutino battle, precisely because of its inconsistencies, was the same , which was needed during that period of the campaign. It is difficult and impossible to imagine any outcome of this battle that would be more expedient than the one it had. With the least tension, with the greatest confusion and with the most insignificant loss, the greatest results of the entire campaign were achieved, the transition from retreat to offensive was made, the weakness of the French was exposed and the impetus that Napoleon’s army had only been waiting for to begin their flight was given.

Napoleon enters Moscow after a brilliant victory de la Moskowa; there can be no doubt about victory, since the battlefield remains with the French. The Russians retreat and give up the capital. Moscow, filled with provisions, weapons, shells and untold riches, is in the hands of Napoleon. The Russian army, twice as weak as the French, did not make a single attack attempt for a month. Napoleon's position is most brilliant. In order to fall with double forces on the remnants of the Russian army and destroy it, in order to negotiate an advantageous peace or, in case of refusal, to make a threatening move towards St. Petersburg, in order to even, in case of failure, return to Smolensk or Vilna , or stay in Moscow - in order, in a word, to maintain the brilliant position in which the French army was at that time, it would seem that no special genius is needed. To do this, it was necessary to do the simplest and easiest thing: to prevent the troops from looting, to prepare winter clothes, which would be enough in Moscow for the entire army, and to properly collect the provisions that were in Moscow for more than six months (according to French historians) for the entire army. Napoleon, this most brilliant of geniuses and who had the power to control the army, as historians say, did nothing of this.

Not only did he not do any of this, but, on the contrary, he used his power to choose from all the paths of activity that presented itself to him that which was the stupidest and most destructive of all. Of all the things that Napoleon could do: winter in Moscow, go to St. Petersburg, go to Nizhny Novgorod, go back, north or south, the way that Kutuzov later went - well, whatever he could come up with, was stupider and more destructive than what he did Napoleon, that is, to remain in Moscow until October, leaving the troops to plunder the city, then, hesitating, to leave or not to leave the garrison, to leave Moscow, to approach Kutuzov, not to start a battle, to go to the right, to reach Maly Yaroslavets, again without experiencing the chance of breaking through , to go not along the road that Kutuzov took, but to go back to Mozhaisk and along the devastated Smolensk road - nothing more stupid than this, nothing more destructive for the army could be imagined, as the consequences showed. Let the most skillful strategists come up with, imagining that Napoleon’s goal was to destroy his army, come up with another series of actions that would, with the same certainty and independence from everything that the Russian troops did, would destroy the entire French army, like what Napoleon did.

The genius Napoleon did it. But to say that Napoleon destroyed his army because he wanted it, or because he was very stupid, would be just as unfair as to say that Napoleon brought his troops to Moscow because he wanted it, and because that he was very smart and brilliant.

In both cases, his personal activity, which had no more power than the personal activity of each soldier, only coincided with the laws according to which the phenomenon took place.

It is completely false (only because the consequences did not justify Napoleon’s activities) that historians present to us Napoleon’s forces as weakened in Moscow. He, just as before and after, in the 13th year, used all his skill and strength to do the best for himself and his army. Napoleon's activities during this time were no less amazing than in Egypt, Italy, Austria and Prussia. We do not know truly the extent to which Napoleon’s genius was real in Egypt, where forty centuries they looked at his greatness, because all these great exploits were described to us only by the French. We cannot correctly judge his genius in Austria and Prussia, since information about his activities there must be drawn from French and German sources; and the incomprehensible surrender of corps without battles and fortresses without siege should incline the Germans to recognize genius as the only explanation for the war that was waged in Germany. But, thank God, there is no reason for us to recognize his genius in order to hide our shame. We paid for the right to look at the matter simply and directly, and we will not give up this right.

His work in Moscow is as amazing and ingenious as everywhere else. Orders after orders and plans after plans emanate from him from the time he entered Moscow until he left it. The absence of residents and deputations and the very fire of Moscow do not bother him. He does not lose sight of the welfare of his army, nor the actions of the enemy, nor the welfare of the peoples of Russia, nor the administration of the valleys of Paris, nor diplomatic considerations about the upcoming conditions of peace.

In military terms, immediately upon entering Moscow, Napoleon strictly orders General Sebastiani to monitor the movements of the Russian army, sends corps along different roads and orders Murat to find Kutuzov. Then he diligently gives orders to strengthen the Kremlin; then he makes an ingenious plan for a future campaign across the entire map of Russia. In terms of diplomacy, Napoleon calls to himself the robbed and ragged captain Yakovlev, who does not know how to get out of Moscow, sets out to him in detail all his policies and his generosity and, writing a letter to Emperor Alexander, in which he considers it his duty to inform his friend and brother that Rastopchin made bad decisions in Moscow, he sends Yakovlev to St. Petersburg. Having outlined his views and generosity in the same detail to Tutolmin, he sends this old man to St. Petersburg for negotiations.

In legal terms, immediately after the fires, it was ordered to find the perpetrators and execute them. And the villain Rostopchin is punished by being ordered to burn his house.

In administrative terms, Moscow was granted a constitution, a municipality was established and the following was promulgated:

“Residents of Moscow!

Your misfortunes are cruel, but His Majesty the Emperor and King wants to stop their course. Terrible examples have taught you how he punishes disobedience and crime. Strict measures are taken to stop the disorder and restore everyone's safety. The paternal administration, elected from among yourself, will constitute your municipality or city government. It will care about you, about your needs, about your benefit. Its members are distinguished by a red ribbon, which will be worn over the shoulder, and the city head will have a white belt on top of it. But, except during their office, they will only have a red ribbon around their left hand.

The city police were established according to the previous situation, and through its activities a better order exists. The government appointed two general commissars, or chiefs of police, and twenty commissars, or private bailiffs, stationed in all parts of the city. You will recognize them by the white ribbon they will wear around their left arm. Some churches of different denominations are open, and divine services are celebrated in them without hindrance. Your fellow citizens return daily to their homes, and orders have been given that they should find in them help and protection following misfortune. These are the means that the government used to restore order and alleviate your situation; but in order to achieve this, it is necessary that you unite your efforts with him, so that you forget, if possible, your misfortunes that you have endured, surrender to the hope of a less cruel fate, be sure that an inevitable and shameful death awaits those who dare to your persons and your remaining property, and in the end there was no doubt that they would be preserved, for such is the will of the greatest and fairest of all monarchs. Soldiers and residents, no matter what nation you are! Restore public trust, the source of happiness of the state, live like brothers, give mutual help and protection to each other, unite to refute the intentions of evil-minded people, obey the military and civil authorities, and soon your tears will stop flowing.”

Prussian blue is a bright blue pigment used as a dye and goes by different names, each more beautiful than the last. Parisian and iron blue, iron and Hamburg blue, Prussian blue, milori. This is only a small part of the names under which this substance is found.

History of the name

It is not known for certain about the place where Prussian blue was first obtained. Presumably, this happened at the beginning of the 18th century in the city of Berlin. Hence the name of the substance. And it was received by the German master Diesbach, who developed dyes. He experimented with potassium carbonate and one day a solution of iron salts and potash (the second name for carbonate) gave an unexpected, simply magnificent blue color.

A little later, Diesbach discovered that he had used calcined potash, which was in a vessel stained with ox blood. The cheap way in which iron glaze was produced, as well as its resistance to acids, richness of color and breadth of use promised huge profits for the manufacturer. Not surprisingly, Diesbach kept how Prussian blue was produced a secret. Its receipt was revealed 20 years later by John Woodward.

Methods of obtaining

John Woodward's recipe: calcine the animal's blood with potassium carbonate, add water and a solution of ferrous sulfate, in which aluminum alum has previously been dissolved. Add a little acid to the mixture, then Prussian blue will form. Later, chemist Pierre Joseph Maceur from France proved that any part of the remains perfectly replaces blood, the result is the same.

Now you can produce Prussian blue using another, “bloodless” method. Iron sulfate in the form of a solution is added to heated yellow blood salt dissolved in water. A white substance precipitates and turns blue when exposed to air. This is Prussian blue. To speed up the process of turning the white sediment blue, you can add a little acid or chlorine.

In 1822, Leopold Gmelin, a German chemist, obtained red blood salt, the empirical formula of which is K 3, in which the oxidation state of iron is +3, and not +2, as in yellow blood salt. When reacted with ferrous sulfate, it also gives an intense blue color. The substance obtained in this way was named Turnbull blue in honor of the founder of the Arthur and Turnbull company.

Only in the 20th century did they prove that one substance, obtained in different ways, is hidden under different names. Whether you call it Turnboole blue or Prussian blue, the formula will be the same:

KFe III H 2 O,

where in the crystal lattice Fe 2+ atoms tend to be located between carbon atoms, and Fe 3+ - between nitrogen atoms.

Properties

Parisian blue has many shades from azure to dark, rich blue. Moreover, the greater the number of potassium ions contained, the lighter the color will be.

The hiding power of iron glaze varies and depends on the shade. Varies from 10 (for light) to 20 g per square meter.

Prussian blue does not dissolve in water, contains a cyanide group, but is absolutely safe for health and non-toxic even if it enters the stomach. The coloring ability is very high and does not fade under the influence of sunlight. Withstands heat up to 180°C and is resistant to acids. But it decomposes almost instantly in an alkaline environment.

Prussian blue occurs in both colloidal and insoluble forms. Insoluble is a semiconductor. Another interesting property of the crystal was recently discovered: when cooled to 5.5°K, it becomes ferromagnetic.

Application

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Hamburg blue was used in the production of blue paints. But they turned out to be unstable and were destroyed under the influence of an alkaline environment. This is why Prussian blue is not suitable for painting plaster.

Today, milori is not widely used. Most often it is used in printing; polymers, in particular polyethylene, are also tinted with it.

In medicine, the substance is used as an antidote for poisoning by cesium and thallium radionuclides.

It is also used in veterinary medicine. If animals receive a small amount of blue every day, then radionuclides are not deposited in milk, meat and liver. This property was used after Chernobyl in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

History and origin of the name

The exact date of receipt of Prussian blue is unknown. According to the most common version, it was obtained at the beginning of the eighteenth century (some sources give the date) in Berlin by the dyer Diesbach. The intense bright blue color of the compound and the location of its origin give rise to the name. From a modern point of view, the production of Prussian blue consisted of the precipitation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (II) by adding iron (II) salts (for example, “iron sulfate”) to the “yellow blood salt” and subsequent oxidation to iron (II) hexacyanoferrate ( III). It was possible to do without oxidation if iron (III) salts were immediately added to the “yellow blood salt”.

Receipt

Prussian blue can be obtained by adding ferric iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) (“yellow blood salt”). In this case, depending on the conditions, the reaction can proceed according to the equations:

Fe III Cl 3 + K 4 → KFe III + 3KCl,

or, in ionic form

Fe 3+ + 4- → -

The resulting potassium iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II) is soluble and is therefore called "soluble Prussian blue".

The structural diagram of soluble Prussian blue (crystalline hydrate of the type KFe III ·H 2 O) is shown in the figure. It shows that the Fe 2+ and Fe 3+ atoms are located in the crystal lattice in the same way, but in relation to the cyanide groups they are unequal; the prevailing tendency is to be located between carbon atoms, and Fe 3+ - between nitrogen atoms.

4Fe III Cl 3 + 3K 4 → Fe III 4 3 ↓ + 12KCl,

or, in ionic form

4Fe 3+ + 3 4- → Fe III 4 3 ↓

The resulting insoluble (solubility 2·10 -6 mol/l) precipitate of iron (III) hexacyanoferrate (II) is called "insoluble Prussian blue".

The above reactions are used in analytical chemistry to determine the presence of Fe 3+ ions

Another method is to add divalent iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) (“red blood salt”). The reaction also occurs with the formation of soluble and insoluble forms (see above), for example, according to the equation (in ionic form):

4Fe 2+ + 3 3- → Fe III 4 3 ↓

Previously, it was believed that this resulted in the formation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (III), that is, Fe II 3 2, this is exactly the formula proposed for “Turnboole blue”. It is now known (see above) that Turnboole blue and Prussian blue are the same substance, and during the reaction, electrons transfer from Fe 2+ ions to hexacyanoferrate (III) ion (valence rearrangement of Fe 2+ + to Fe 3 + + occurs almost instantly; the reverse reaction can be carried out in a vacuum at 300°C).

This reaction is also analytical and is used, accordingly, for the determination of Fe 2+ ions.

In the ancient method of producing Prussian blue, when solutions of yellow blood salt and iron sulfate were mixed, the reaction proceeded according to the equation:

Fe II SO 4 + K 4 → K 2 Fe II + K 2 SO 4.

The resulting white precipitate of potassium-iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (II) (Everitt's salt) is quickly oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to potassium-iron (III) hexacyanoferrate (II), i.e., Prussian blue.

Properties

The thermal decomposition of Prussian blue follows the following schemes:

at 200°C:

3Fe 4 3 →(t) 6(CN) 2 + 7Fe 2

at 560°C:

Fe 2 →(t) 3N 2 + Fe 3 C + 5C

An interesting property of the insoluble form of Prussian blue is that, being a semiconductor, when cooled very strongly (below 5.5 K) it becomes a ferromagnet - a unique property among metal coordination compounds.

Application

As a Pigment

The color of iron blue changes from dark blue to light blue as the potassium content increases. The intense bright blue color of Prussian blue is probably due to the simultaneous presence of iron in different oxidation states, since the presence of one element in different oxidation states in compounds often gives the appearance or intensification of color.

Dark azure is hard, difficult to wet and disperse, glazes in paints and, when floating up, gives a mirror reflection of yellow-red rays (“bronzing”).

Iron glaze, due to its good hiding power and beautiful blue color, is widely used as a pigment for the manufacture of paints and enamels.

It is also used in the production of printing inks, blue carbon paper, and tinting colorless polymers such as polyethylene.

The use of iron glaze is limited by its instability in relation to alkalis, under the influence of which it decomposes with the release of iron hydroxide Fe(OH) 3. It cannot be used in composite materials containing alkaline components, and for painting on lime plaster.

In such materials, the organic pigment phthalocyanine blue is usually used as a blue pigment.

As a medicine

Other Applications

Before wet copying of documents and drawings was replaced by dry copying, Prussian blue was the main pigment produced in the process. photocopying(so-called “blueing”, cyanotype process).

In a mixture with oily materials, it is used to control the tightness of surfaces and the quality of their processing. To do this, the surfaces are rubbed with the specified mixture, then combined. Remains of unerased blue mixture indicate deeper places.

Also used as a complexing agent, for example to produce prussids.

Toxicity

It is not a toxic substance, although it contains the cyanide anion CN -, since it is firmly bound in the stable complex hexacyanoferrate 4-anion (the instability constant of this anion is only 4·10 -36).

| Shades of blue | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alice blue | Azure | Blue | Cerulean | Cerulean blue | Cobalt blue | Cornflower blue | Dark blue | Denim | Dodger blue | Indigo | International Klein Blue |

| #F0F8FF | #007FFF | #0000FF | #007BA7 | ||||||||

| Lavender | Night blue | Navy blue | Periwinkle | Persian blue | Powder blue | Prussian blue | Royal blue | Sapphire | Steel blue | Ultramarine | Light blue |

| #B57EDC | #003366 | #CCCCFF | |||||||||

| baby blue | |||||||||||

(CN) 6 ] to Fe 4 3 . Turnboole blue obtained by other methods, for which one would expect the formula Fe 3 2, is in fact the same mixture of substances.

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 3

✪ Iron and its compounds

✪ How to draw a night city by artist Jeremy Mann

✪ Determination of nitrogen in organic compounds

Subtitles

History and origin of the name

The exact date of receipt of Prussian blue is unknown. According to the most common version, it was obtained at the beginning of the eighteenth century (1706) in Berlin by the dyer Diesbach. In some sources he is called Johann Jacob Diesbach (German: Johann Jacob Diesbach). The intense bright blue color of the compound and the location of its origin give rise to the name. From a modern point of view, the production of Prussian blue consisted of the precipitation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (II) by adding iron (II) salts (for example, “iron sulfate”) to the “yellow blood salt” and subsequent oxidation to iron hexacyanoferrate (II) ( III). It was possible to do without oxidation if iron (III) salts were immediately added to the “yellow blood salt”.

Under the name “Paris blue”, purified “Prussian blue” was at one time proposed.

Receipt

The preparation method was kept secret until the publication of the production method by the Englishman Woodward in 1724.

Prussian blue can be obtained by adding ferric iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) ("yellow blood salt"). In this case, depending on the conditions, the reaction can proceed according to the equations:

Fe III Cl 3 + K 4 → KFe III + 3KCl,

or, in ionic form

Fe 3+ + 4− → Fe −

The resulting potassium iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II) is soluble and is therefore called "soluble Prussian blue".

In the structural diagram of soluble Prussian blue (crystalline hydrate of the type KFe III ·H 2 O), Fe 2+ and Fe 3+ atoms are arranged in the crystal lattice in the same way, however, in relation to cyanide groups they are unequal, the tendency is to be located between carbon atoms, and Fe 3 + - between nitrogen atoms.

4Fe III Cl 3 + 3K 4 → Fe III 4 3 ↓ + 12KCl,

or, in ionic form

4Fe 3+ + 3 4− → Fe III 4 3 ↓

The resulting insoluble (solubility 2⋅10 −6 mol/l) precipitate of iron (III) hexacyanoferrate (II) is called "insoluble Prussian blue".

The above reactions are used in analytical chemistry to determine the presence of Fe 3+ ions

Another method is to add divalent iron salts to solutions of potassium hexacyanoferrate (III) (“red blood salt”). The reaction also occurs with the formation of soluble and insoluble forms (see above), for example, according to the equation (in ionic form):

4Fe 2+ + 3 3− → Fe III 4 3 ↓

Previously, it was believed that this resulted in the formation of iron (II) hexacyanoferrate (III), that is, Fe II 3 2, this is exactly the formula proposed for “Turnboole blue”. It is now known (see above) that Turnboole blue and Prussian blue are the same substance, and during the reaction, electrons transfer from Fe 2+ ions to hexacyanoferrate (III) ion (valence rearrangement of Fe 2+ + to Fe 3 + + occurs almost instantly; the reverse reaction can be carried out in a vacuum at 300 °C).

This reaction is also analytical and is used, accordingly, for the determination of Fe 2+ ions.

In the ancient method of producing Prussian blue, when solutions of yellow blood salt and iron sulfate were mixed, the reaction proceeded according to the equation:

Fe II SO 4 + K 4 → K 2 Fe II + K 2 SO 4.

The resulting white precipitate of potassium-iron(II) hexacyanoferrate(II) (Everitt's salt) is quickly oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to potassium-iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II), that is, Prussian blue.

Properties

The thermal decomposition of Prussian blue follows the following schemes:

at 200 °C:

3Fe 4 3 →(t) 6(CN) 2 + 7Fe 2

at 560 °C:

Fe 2 →(t) 3N 2 + Fe 3 C + 5C

An interesting property of the insoluble form of Prussian blue is that, being a semiconductor, when cooled very strongly (below 5.5 K) it becomes a ferromagnet - a unique property among metal coordination compounds.

Application

As a pigment

The color of iron blue changes from dark blue to light blue as the potassium content increases. The intense bright blue color of Prussian blue is probably due to the simultaneous presence of iron in different oxidation states, since the presence of one element in different oxidation states in compounds often gives rise to or intensification of color.

Dark azure is hard, difficult to wet and disperse, glazes in paints and, when floating up, gives a mirror reflection of yellow-red rays (“bronzing”).

Iron glaze, due to its good hiding power and beautiful blue color, is widely used as a pigment for the manufacture of paints and enamels.

It is also used in the production of printing inks, blue carbon paper, and tinting colorless polymers such as polyethylene.

The use of iron glaze is limited by its instability in relation to alkalis, under the influence of which it decomposes with the release of iron hydroxide Fe(OH) 3. It cannot be used in composite materials containing alkaline components, and for painting on lime plaster.

In such materials, the organic pigment phthalocyanine blue is usually used as a blue pigment.

Medicine

Also used as an antidote (Ferrocin tablets) for poisoning with thallium and cesium salts, to bind radioactive nuclides entering the gastrointestinal tract and thereby prevent their absorption. ATX code V03AB31. The pharmacopoeial drug Ferrocin was approved by the Pharmaceutical Committee and the USSR Ministry of Health in 1978 for use in acute human poisoning with cesium isotopes. Ferrocine consists of 5% potassium iron hexacyanoferrate KFe and 95% iron hexacyanoferrate Fe43.

Veterinary drug

To rehabilitate lands contaminated after the Chernobyl disaster, a veterinary drug was created based on the medical active component Ferrocin-Bifezh. Included in the State Register of Medicines for Veterinary Use under number 46-3-16.12-0827 No. PVR-3-5.5/01571.

Other Applications

Before wet copying of documents and drawings was replaced by dry copying, Prussian blue was the main pigment produced in the process. photocopying(so-called “blueing”, cyanotype process).

In a mixture with oily materials, it is used to control the tightness of surfaces and the quality of their processing. To do this, the surfaces are rubbed with the specified mixture, then combined. Remains of unerased blue mixture indicate deeper places.

Also used as a complexing agent, for example to produce prussids.

In the 19th century, it was used in Russia and China to tint dormant tea leaves, as well as to recolor black tea green.

Toxicity

It is not a toxic substance, although it contains the cyanide anion CN−, since it is firmly bound in the stable complex hexacyanoferrate 4− anion (the instability constant of this anion is only 4⋅10−36).