CHECHENS, Nokhchiy (self-name), people in Russian Federation(899 thousand people), the main population of Chechnya. The number in Chechnya and Ingushetia is 734 thousand people. They also live in Dagestan (about 58 thousand people), Stavropol Territory (15 thousand people), Volgograd Region (11.1 thousand people), Kalmykia (8.3 thousand people), Astrakhan (7.9 thousand people) ), Saratov (6 thousand people), Tyumen (4.6 thousand people) region, North Ossetia (2.6 thousand people), Moscow (2.1 thousand people), as well as in Kazakhstan (49.5 thousand people), Kyrgyzstan (2.6 thousand people), Ukraine (1.8 thousand people), etc. The total number is 957 thousand people.

Believing Chechens are Sunni Muslims. There are two widespread Sufi teachings - Naqshbandi and Nadiri. They speak the Chechen language of the Nakh-Dagestan group. Dialects: flat, Akkinsky, Cheberloevsky, Melkhinsky, Itumkalinsky, Galanchozhsky, Kistinsky. The Russian language is also widespread (74% speak fluently). Writing after 1917 was first based on Arabic, then on Latin script, and from 1938 on the Russian alphabet.

Strabo's "Geography" mentions the ethnonym Gargarei, the etymology of which is close to the Nakh "gergara" - "native", "close". The ethnonyms Isadiks, Dvals, etc. are also considered Nakh. In Armenian sources of the 7th century, the Chechens are mentioned under the name Nakhcha Matyan (i.e. “speaking the Nokhchi language”). In the chronicles of the 14th century, the “people of Nokhchi” are mentioned. Persian sources of the 13th century give the name sasana, which was later included in Russian documents. In documents from the 16th and 17th centuries, the tribal names of the Chechens are found (Ichkerins - Nokhchmakhkhoy, Okoks - A'kkhii, Shubuts - Shatoi, Charbili - Cheberloi, Melki - Malkhii, Chantins - ChIantiy, Sharoyts - Sharoy, Terloyts - TIerloy).

The anthropological type of Pranakhs can be considered formed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages. The ancient Chechens, who mastered not only the northern slopes of the Caucasus, but also the steppes of the Ciscaucasia, early came into contact with the Scythian, and then with the Sarmatian and Alan nomadic world. In the flat zone of Chechnya and nearby regions of the North Caucasus in the 8th-12th centuries, the multi-ethnic Alan kingdom was formed, in the mountainous zone of Chechnya and Dagestan - the state formation of Sarir. After the Mongol-Tatar invasion (1222 and 1238-1240), the steppe beyond the border and partly the Chechen plain became part of the Golden Horde. By the end of the 14th century, the population of Chechnya united into the state of Simsism. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Caucasian Isthmus was the object of constant claims Ottoman Empire(with its vassal - the Crimean Khanate), Iran and Russia. In the course of the struggle between these states, the first Russian fortresses and Cossack towns were erected on Chechen lands, and diplomatic ties between Chechen rulers and aul societies were established with Russia. At the same time, the modern borders of Chechen settlement were finally formed. Since the Persian campaign of Peter I (1722), Russia's policy towards Chechnya has acquired a colonial character. IN last years During the reign of Catherine II, Russian troops occupied the left bank of the Terek, building a section of the Caucasian military line here, and founded military fortresses from Mozdok to Vladikavkaz along the Chechen-Kabardian border. This led to an increase liberation movement Chechens at the end of the 18th-1st half of the 19th century. By 1840, a theocratic state was emerging on the territory of Chechnya and Dagestan - the Imamate of Shamil, which initially waged a successful war with Russia, but was defeated by 1859, after which Chechnya was annexed to Russia and included, together with the Khasavyurt district, populated by Aukhov Chechens and Kumyks, in the Terek region . In 1922, the Chechen Autonomous Region was formed as part of the RSFSR. Even earlier, part of the lands taken from it during the Caucasian War was returned to Chechnya. Office work and teaching were introduced in native language, other cultural and socio-economic transformations were carried out. At the same time, collectivization that began in the 1920s, accompanied by repressions, caused great damage to the Chechens. In 1934, Chechnya was united with the Ingush Autonomous Okrug into the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Okrug, and since 1936 - the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In February 1944, about 500 thousand Chechens and Ingush were forcibly deported to Kazakhstan. Of these, a significant number died in the first year of exile. In January 1957, the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, abolished in 1944, was restored. But at the same time, several mountainous regions were closed to the Chechens, and the former residents of these regions began to be settled in lowland villages and Cossack villages. Chechen Aukhovites returned to Dagestan.

At the 1992 congress people's deputies The Russian Federation decided to transform the Chechen-Ingush Republic into the Ingush Republic and the Chechen Republic.

Traditional agricultural crops are barley, wheat, millet, oats, rye, flax, beans, etc. Later they began to grow corn and watermelons. Gardening and horticulture were developed. Arable tools - plow (gota), skid implement (nokh). The three-field system was widespread. Transhumance sheep breeding was developed in the mountainous regions. Cattle were raised on the plains, which were also used as labor. They also bred thoroughbred horses for riding. There was economic specialization between the mountainous and lowland regions of Chechnya: receiving grain from the plains, mountain Chechens sold their surplus livestock in return.

Handicrafts played an important role. Chechen cloth, produced in the Grozny, Vedensky, Khasavyurt, and Argun districts, was very popular. Leather processing and the production of felt carpets, buroks and other felt products were widespread. The centers of weapons production were the villages of Starye Atagi, Vedeno, Dargo, Shatoi, Dzhugurty, etc., and the centers of pottery production were the villages of Shali, Duba-Yurt, Stary-Yurt, Novy-Yurt, etc. Jewelry and blacksmithing, mining, and production were also developed. silk, processing of bone and horn.

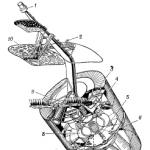

Mountain villages had a disorderly, crowded layout. Two-story ones were common stone houses with a flat roof. The lower floor housed livestock, and the upper floor, which consisted of two rooms, housed housing. Many villages had housing and defense towers of 3-5 floors. Settlements on the plain were large (500-600 and even up to 4000 households), stretched along roads and rivers. The traditional dwelling - turluchnoe - consisted of several rooms, stretched in a row, with separate exits to the terrace that ran along the house. The main room belonged to the head of the family. Here was the hearth and the whole life of the family took place. The rooms of married sons were attached to it. One of the rooms served as a kunat room, or a special building was erected for it in the courtyard. The yard with outbuildings was usually surrounded by a fence. Distinctive feature The interior of the Chechen home had an almost complete absence of furniture: a chest, a low table on three legs, several benches. The walls were hung with skins and carpets, weapons were hung on them, and the floor was covered with mats. The hearth, the chain of fire, the ash were considered sacred, disrespect for them entailed blood feud and, conversely, even if the murderer grabbed the chain of fire, he received the rights of a relative. They swore and cursed with the chain above them. The eldest woman was considered the keeper of the hearth. The fireplace divided the room into male and female halves.

Woolen fabrics were of several types. Highest quality the fabric "iskhar" was considered to be made from the wool of lambs, the lower - from the wool of dairy sheep. No later than the 16th century, the Chechens knew the production of silk and linen. Traditional clothing had much in common with the general Caucasian costume. Men's clothing - shirt, trousers, beshmet, Circassian coat. The shirt was tunic-shaped, the collar with a slit in the front was fastened with buttons. A beshmet was worn over the shirt, belted with a belt with a dagger. The Circassian coat was considered festive clothing. Circassian shorts were sewn cut off at the waist, flared downwards, fastened to the waist with metal fasteners, and gazyrnitsa were sewn onto the chest. Pants, tapered downwards, were tucked into leggings made of cloth, morocco or sheepskin. Winter clothing - sheepskin coat, burka (verta). Men's hats were tall, flaring hats made of valuable fur. Shepherds wore fur hats. There were also felt hats. The hat was considered the personification of masculine dignity; knocking it down would entail blood feud.

The main elements of women's clothing were a shirt and trousers. The shirt had a tunic-like cut, sometimes below the knees, sometimes to the ground. The collar with a slit on the chest was fastened with one or three buttons. The outerwear was a beshmet. Festive clothing was “gIables” made of silk, velvet and brocade, sewn to fit the figure, with beveled sides and fasteners to the waist, of which only the lower ones were fastened. Hanging blades (tIemash) were sewn on top of the sleeves. Giables were worn with a breastplate and a belt. Women wore high-heeled shoes with a flat toe without a back as formal footwear.

Women's headdresses - large and small scarves, shawls (cortals), one end of which went down to the chest, the other was thrown back. Women (mostly elderly) wore a chukhta under a headscarf - a hat with bags that went down the back, into which the braids were placed. The color of clothing was determined by the woman's status: married, unmarried or widow.

Food in spring is predominantly plant-based, in summer - fruits and dairy dishes, in winter - mainly meat. Everyday food is siskal-beram (churek with cheese), soups, porridges, pancakes (shuri chIepalI-ash), for the wealthier - kald-dyattiy (cottage cheese with butter), zhizha-galnash (meat with dumplings), meat broth, flatbreads with cheese, meat, pumpkin, etc.

The dominant form of community was the neighborhood one, consisting of families of both Chechen and sometimes other ethnic origins. It united residents of one large or several small settlements. The life of the community was regulated by a gathering (khel - “council”, “court”) of representatives of clan divisions (taip). He decided judicial and other cases of community members. The gathering of the entire community (“community khel”) regulated the use of community lands, determined the timing of plowing and haymaking, acted as a mediator in the reconciliation of bloodlines, etc. In the mountains, tribal settlements were also preserved, subdivided into smaller kin groups (gar), as well as large associations of taips (tukhums), differing in the peculiarities of their dialects. There were slaves from unredeemed prisoners of war who for long service could receive land from the owner and the right to start a family, but even after that they remained incomplete members of the community. The customs of hospitality, kunakship, twinning, tribal and neighborly mutual assistance (belkhi - from “bolkh”, “work”), and blood feud remained of great importance. The most serious crimes were considered to be the murder of a guest, a forgiven blood relative, rape, etc. The issue of declaring blood feud was decided by the elders of the community, the possibility and conditions of reconciliation were decided at general gatherings. Revenge, punishment, and murder could not take place in the presence of a woman; moreover, by throwing a scarf from her head into the middle of the fighters, a woman could stop the bloodshed. The customs of avoidance persisted in the relationships between husband and wife, son-in-law and in-laws, daughter-in-law and in-laws, parents and children. In some places, polygamy and levirate were preserved. Clan associations were not exogamous, marriages were prohibited between relatives up to the third generation.

There are various forms of folklore: traditions, legends, fairy tales, songs, epic tales (Nart-Ortskhoi epic, Illi epic, etc.), dances. Musical instruments- harmonica, zurna, tambourine, drum, etc. The veneration of mountains, trees, groves, etc. has been preserved. The main deities of the pre-Muslim pantheon were the god of the sun and sky Del, the god of thunder and lightning Sel, the patron of cattle breeding Gal-Erdy, hunting - Elta, the goddess of fertility Tusholi, the god of the underworld Eshtr, etc. Islam penetrates Chechnya from the 13th century through the Golden Horde and Dagestan . The Chechens were completely converted to Islam by the 18th century. In the 20th century, the Chechen intelligentsia was formed.

Ya.Z. Akhmadov, A.I. Khasbulatov, Z.I. Khasbulatova, S.A. Khasiev, Kh.A. Khizriev, D.Yu. Chakhkiev

According to the 2002 Population Census, the number of Chechens living in Russia is 1 million 361 thousand people.

Self-name: Nokhchi, nokhcho, nakhchu, nakhche, nakhchi, nokhche

Total number: about 1.5 million people worldwide

Settlement:

| Russia - 1 400 253 (2002) | Kabardino-Balkaria - 4 200 (2002) | |

| Chechen Republic - 1 031 000 (2002) | North Ossetia - 3 400(2002) | |

| The Republic of Ingushetia - 95 000 (2002) | Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug - 2 222 (2002) | |

| The Republic of Dagestan- 87 900 (2002) | Voronezh region - 1 815 (2002) | |

| Rostov region - 15 469 (2002) | Oryol Region - 1 630 (2002) | |

| Moscow - 14 465 (2002) | Tyumen region - 1 458 (2002) | |

| Stavropol region- 13 200 (2002) | Türkiye- 100 000 | |

| Volgograd region - 12 300 (2002) | Kazakhstan- 34 000 (2004) | |

| Saint Petersburg - 11 000 (2002) | Jordan- 15 000 | |

| Astrakhan region - 10 000 (2002) | Azerbaijan- 10,000 (2007 estimate) | |

| Saratov region- 8 500 (2002) | Georgia- 4 000 (2007) | |

| Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug- 6 943 (2002) | Kyrgyzstan- 4 000 (2008) | |

| Kalmykia - 6 000 (2002) |

Language: Chechen

Religion: Islam

Related peoples: Ingush, Batsbians

Chechens (self-name Nokhchi, singular - Nokhcho (translated as "Noah's people", "people of Noah"; "Nokh"/"Noah" - Noah, "Che"/"Chii" - suffix of belonging. Possibly transferred from forms "tsIi" - blood, offspring) - the most numerous autochthonous people of the North Caucasus, numbering about 1.5 million people worldwide, the main population

Chechnya.

resettlement,anthropology

At present absolute majority Chechens live on the territory of the Russian Federation, namely in the Chechen Republic. In the history of the Chechen people there have been several settlements.

After the Caucasian War in 1865, about 5,000 Chechen families moved to the Ottoman Empire, a movement that took the name Muhajirism. Today, the descendants of those settlers make up the bulk of the Chechen diasporas in Turkey, Syria and Jordan.

In February 1944, more than half a million Chechens were completely deported from their places of origin. permanent residence to Central Asia. On January 9, 1957, Chechens were allowed to return to their previous place of residence, while a number of Chechens remained in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

After the First and Second Chechen Wars, a significant number of Chechens left for Western European countries, Turkey and Arab countries. The Chechen diaspora in the regions of the Russian Federation has also increased significantly.

They belong to the Caucasian version of the Balkan-Caucasian race of the large Caucasian race.

Story

History of the ethnonym

The ethnonym “Chechens” is of Turkic origin, most likely from the village of Chechen-aul. Kabardians call them shashen, Ossetians - ts?ts?n, Avars - burtiel, Georgians - kists, dzurdzuki.

Theories of the origin of the Chechens

The problem of the origin and earliest stage of the history of the Chechens remains completely unclear and debatable, although their deep autochthony in the North-Eastern Caucasus and a wider area of settlement in ancient times seem quite obvious. A massive movement of proto-Vainakh tribes from Transcaucasia to the north of the Caucasus is not excluded, but the time, reasons and circumstances of this migration, recognized by a number of scientists, remain at the level of assumptions and hypotheses.

Based on the research of V. M. Illich-Svitych and A. Yu. Militarev, a number of other major linguists, when correlating their data with archaeological materials, in particular A. K. Vekua, the fundamental works of T. V. Gamkrelidze and V. Ivanov, A. Arordi, M. Gavukchyan and others, we can come to the following conclusions regarding the origin and settlement of representatives of the ancient ethnolanguage of the Vainakhs.

Sino-Caucasian - within the Armenian Highlands and Anatolia - Armenian Mesopotamia (not only ancient and some modern languages of the Mediterranean and Caucasus are genetically associated with it, such as Hittite, Hurrian, "Urartian", Abkhaz-Adyghe and Nakh-Dagestan, in particular Chechen, Lezgian, etc., but also, oddly enough, the languages of the Sino-Tibetan group, including Chinese).

The pronostratic community in its modern understanding took shape in the Armenian Highlands [source not specified 23 days]. From its southeastern part, the descendants of representatives of the western area of the Sino-Caucasian community during the 9th-6th millennium BC. e. spread throughout the Northern Mediterranean, the Balkan-Danube region, the Black Sea region and the Caucasus. Their relics are known as the Basques in the Pyrenees and the Adyghe or Chechens in the Caucasus Mountains. The northern neighbors of the ancient Semites were speakers of the ancient Anatolian-North Caucasian languages, represented mainly by two branches of the western, Hattian - in Asia Minor (with branches in the North Caucasus in the form of the linguistic ancestors of the Abkhaz-Adyghe peoples), and eastern, Hurrian - in the Armenian Highlands ( with branches in the North Caucasus in the form of the ancestors of the Nakh-Dagestan peoples).

The written source about the ancient period of Vainakh history is the work of a major Armenian encyclopedist of the 6th century. Anania Shirakatsi “Armenian Geography” in which for the first time the self-name of the Chechens “Nokhchamatyans” is mentioned - people who speak Chechen: At the mouth of the Tanais River live the Nakhchamateans [Naxamats] and another tribe (From the text “Ashkharatsuyts” translated by Gabrielyan, 2006:168).

The main trade routes connecting the peoples of Europe and the East passed through the territory of Chechnya, which occupies a very important strategic position. Archaeological excavations show that the ancestors of the Chechens had extensive trade and economic ties with the peoples of Asia and Europe.

Chechens in Russian history

The name “Chechens” itself was a Russian transliteration of the Kabardian name “Shashan” and came from the village of Bolshoi Chechen. From the beginning of the 18th century, Russian and Georgian sources began to call all inhabitants of modern Chechnya “Chechens”.

Even before the Caucasian War, at the beginning of the 18th century, after the Grebensky Cossacks left the Terek right bank, many Chechens who agreed to voluntarily accept Russian citizenship were given the opportunity to move there in 1735 and then in 1765.

On January 21, 1781 and confirmed in the fall of the same year, a document was signed on the basis of which mountainous Chechnya became part of Russia. On the Chechen side, it was signed by the most honorable elders of the villages of Bolshie and Malye Atagi, Gekhi, Mozdok and twelve other villages, that is, the entire Chechen Republic in the current sense. This document was sealed with signatures in Russian and Arabic and an oath in the Koran. But in many ways, this document remained a formality, although the Russian Empire received the official “right” to involve Chechnya into Russia; not all Chechens, especially the influential Sheikh Mansur, came to terms with the new order, and so began the almost century-long Caucasian War.

During the Caucasian War, under the leadership of General Alexei Ermolov, the Sunzha line of fortifications was built in 1817-1822 on the site of some Chechen and Ingush villages. After the capture of Shamil, the destruction of a number of rebel imams, as well as the transition under Field Marshal Ivan Paskevich to the “scorched earth” tactic, when the rebel villages were completely destroyed and the population was completely destroyed, the organized resistance of the mountaineers was suppressed in 1860.

But the end of the Caucasian War did not mean complete peace. Particularly controversial was the land issue, which was far from being in favor of the Chechens. Even by the end of the 19th century, when oil was discovered, almost no income went to the Chechens. The tsarist government managed to maintain relative calm in Chechnya through virtual non-interference in the internal life of the highlanders, bribery of the tribal nobility, free distribution of flour, fabrics, leather, and clothing to the poor highlanders; appointment of local authoritative elders, leaders of teips and tribes as officials.

It is not surprising that the Chechens often rebelled, as happened during the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878 and then during the 1905 revolution. But at the same time, the Chechens were valued by the tsarist authorities for their military courage. From them the Chechen regiment of the elite Wild Division was formed, which distinguished itself in the First World War. They were even taken into the royal convoy, which also consisted of Cossacks and other highlanders. The encyclopedic dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron in 1905 wrote about them: Chechens are considered cheerful, witty people (“the French of the Caucasus”), impressionable, but they enjoy less sympathy than the Circassians, due to their suspicion, tendency to deceit and severity, which probably developed during centuries-old struggle. Indomitability, courage, agility, endurance, calmness in the fight - traits of Ch., long recognized by everyone, even their enemies.

USSR

During Civil War Chechnya turned into a battlefield, and the territory of Chechnya changed several times. After the February Revolution, in March 1917, under the leadership of a former member of his convoy Imperial Majesty, and later the Wild Division of Tapa Chermoev, the Union of Peoples of the North Caucasus was formed, which proclaimed the Mountain Republic in November 1917 (and from May 1918 - the Republic of the Mountain People of the North Caucasus). But the height of the war, the offensive of the Red Army, Denikin quickly ended the republic. Anarchy reigned in Chechnya itself. For the Bolsheviks, the Chechens, like other peoples of the Caucasus, played into the hand, and as a result, after their victory, the Chechens were rewarded with autonomy and a huge amount of land, including almost all the villages of the Sunzhenskaya line, from where the Cossacks were evicted.

In the 1920s, under the policy of indigenization, a huge contribution was made to the development of the Chechens. The writing of the Chechen language was developed, a national theater, musical ensembles and much more appeared. But further integration of the Chechens into the Soviet people was cut short during collectivization, especially when trying to create collective farms in the mountainous regions. Unrest and uprisings continued, especially when the autonomous status of Chechnya again became “formal”, when in 1934 the Chechen Autonomous Okrug was united with the Ingush Autonomous Okrug, and in 1936 with the Sunzhensky Cossack District and the city of Grozny into the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, the leadership of which was actually headed by Russian population.

The uprising of Hasan Israilov in 1940 turned out to be especially intense and continued until 1944. Although many Chechens conscripted into the Red Army distinguished themselves in battle, unrest in Chechnya itself continued, especially as the Germans approached Grozny. In February 1944, the entire Chechen population (about half a million) was deported from their places of permanent residence to Central Asia. On January 9, 1957, the Chechens were allowed to return to their previous place of residence. A certain number of Chechens remained in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

1990s and aftermath

After the First and Second Chechen Wars, a significant number of Chechens left for Western European countries, Turkey and Arab countries. The Chechen diaspora in the regions of the Russian Federation has also increased significantly

Main article: Chechen language

The Chechen language belongs to the Nakh branch of the Nakh-Dagestan languages, included in the hypothetical Sino-Caucasian macrofamily. Distributed mainly in the Chechen Republic and in the Khasavyurt, Novolak, Kazbekovsky, Babayurt and Kizilyurt regions of Dagestan, as well as in Ingushetia and other regions of the Russian Federation and in Georgia, partially in Syria, Jordan and Turkey. Number of speakers before the war 1994-2001 - approx. 1 million people (according to other sources, about 950 thousand). The following dialects are distinguished: Planar, Shatoi, Akkinsky (Aukhovsky), Cheberloevsky, Sharoevsky, Melkhinsky, Itumkalinsky, Galanchozhsky and Kistinsky. In phonetics, the Chechen language is characterized by complex vocalism (contrasting simple and umlauted, long and short vowels, the presence of weak nasalized vowels, a large number of diphthongs and triphthongs), initial combinations of consonants, an abundance of morphonological alternations, primarily changes in the base vowels in different grammatical forms(ablaut); in grammar - six nominal classes, multi-case declension; the composition of verbal categories and ways of expressing them are common for East Caucasian languages. The syntax is characterized by a wide use of participial and participial constructions.

The literary Chechen language developed in the 20th century. based on the plane dialect. Writing in the Chechen language until 1925 existed on an Arabic basis, in 1925-1938 - on Latin, from 1938 - on the basis of Russian graphics using one additional sign I (after different letters it has different meanings), as well as some digraphs (kh, аь, tI, etc.) and trigraphs (уй). The composition of digraphs in the Chechen alphabet is similar to the alphabets of the Dagestan languages, but their meanings are often different. Since 1991, attempts have been made to return to the Latin script. The first monographic description of Chechen was created in the 1860s by P.K. Uslar; Subsequently, significant contributions to the study of the Chechen language were made by N. F. Yakovlev, Z. K. Malsagov, A. G. Matsiev, T. I. Desherieva and other researchers.

Is state language Chechen Republic.

Religion

Sufi Islam among the Chechens is represented by two tariqats: the Naqshbandiyya and the Qadiriyya, which in turn are divided into small religious groups - vird brotherhoods, the total number of which among the Chechens reaches thirty-two. The largest Sufi brotherhood in Chechnya are the followers of the Chechen Qadiri sheikh Kunta-Hadzhi Kishiev (“zikrists”) and the small virds that spun off from him - Bammat-Girey-Hadzhi, Chimmmirza, Mani-sheikh.

Chechen tukhums and teips

Main articles: Teip, Tukkhum

The Chechen tukhum is a union of a certain group of teips that are not related to each other by blood, but have united into a higher association to jointly solve common problems - protection from enemy attacks and economic exchange. Tukkhum occupied a certain territory, which consisted of the area actually inhabited by it, as well as the surrounding area, where the taips included in Tukkhum were engaged in hunting, cattle breeding and agriculture. Each Tukkhum spoke a certain dialect of the Vainakh language.

The Chechen teip is a community of people related to each other by blood on the paternal side. Each of them had their own communal lands and a teip mountain (from the name of which the name of the teip often came). Tapes are internally divided into “gars” (branches) and “nekyi” - surnames. Chechen teips are united into nine tukhums, a kind of territorial unions. Consanguinity among the Chechens served the purposes of economic and military unity.

In the middle of the 19th century, Chechen society consisted of 135 teips. Currently, they are divided into mountain (about 100 teips) and plain (about 70 teips).

Currently, representatives of one teip live dispersedly. Large teips are distributed throughout Chechnya.

List of tukhums and teips included in them:

Akkintsy

1. Akkoy, 2. Barchakhoy, 3. Vyappiy, 4. Zhevoy, 5. Zogoy, 6. Nokkhoy, 7. Pharchakhoy, 8. Pharchoy, 9. Yalkhoroy

Melchi

1. Byastiy, 2. Binasthoy, 3. Zharkhoy, 4. Kamalkhoy, 5. Kegankhoy, 6. Korathoy (Khorathoy), 7. Meshiy, 8. Sahankhoy, 9. Terthoy

Nokhchmakhkahoy

1. Aleroy, 2. Aitkhaloy, 3. Belgatoy, 4. Benoy, 5. Bilttoy (Beltoy), 6. Gordaloy, 7. Gendargenoy, 8. Guna, 9. Dattyhoy, 10. Zandakoy, 11. Ikhirkhoy, 12. Ishkhoy . Enakhaloy, 25. Enganoy, 26. Ersenoy, 27. Yalhoy. 28. Sarbloy

Tierloy

1. Bavloy, 2. Beshni, 3. Zherakhoy, 4. Kenakhoy (Khenakhoy), 5. Matsarkhoy, 6. Nikaroy, 7. Oshny, 8. Sanakhoy, 9. Shuidiy, 10. Eltparhoy.

Chantiy (Chechen ChIaintii)

1.Chantiy (Chechen: CHIanty). 2.Dishny. 3.Zumsoy. 4.Khyacharoy. 5.Hildejaroy. 6.Khokhtoy 7.Herahoy.

Cheberloy

Some of the oldest settlers on Chechen soil, according to the stories of historians and linguists Krupnov.Karts. 1. Arstkhoy, 2. Acheloy, 3. Baskhoy, 4. Begacherkhoy, 5. Barefoot, 6. Bunikhoy, 7. Gulatkhoy, 8. Dai, 9. Zhelashkhoy, 10. Zu'rkhoy, 11. Ikharoy, 12. Kezenoy, 13. Kiri, 14. Kuloy, 15. Lashkaroy, 16. Makazhoy, 17. Nokhchi-keloy, 18. Nuykhoy, 19. Oskharoy, 20. Rigakhoy, 21. Sadoy, 22. Salbyuroy, 23. Sandahoy, 24. Sikkhoy, 25. Sirkhoy, 26. Tundukhoy, 27. Kharkaloy, 28. Hindoy, 29. Khoy, 30. Tsikaroy, 31. Chebyakhkinhoy, 32. Cheremakhkhoy 33. Nizhaloy, 34. Orsoy,

Sharoy

1. Buti, 2. Dunarkhoy, 3. Zhogaldoy, 4. Ikaroy, 5. Kachehoy, 6. Kevaskhoy, 7. Kinkhoy, 8. Kiri, 9. Mazuhoy, 10. Serchihoy, 11. Khashalhoy, 12. Khimoy, 13. Hinduhoy, 14. Khikhoy, 15. Khulandoy, 16. Khyakmadoy, 17. Cheiroy, 18. Shikaroy, 19. Tsesi.

Shatoy

1. Varanda, 2. Vashindar, 3. Gatta, 4. Gorgachkha, 5. Dehesta, 6. Keloy, 7. Muskulhoy, 8. Myarshoy, 9. Nihala, 10. Memory, 11. Ryadukha, 12. Sanoy, 13. Sattoy (Sadoy), 14. Tumsoy (Dumsoy), 15. Urdyukhoy, 16. Hakkoy, 17. Khalkeloy, 18. Khyalg1i, 19. Kharsenoy.

Orsthøy

1. Alkhoy, 2. Andaloy, 3. Belkharoy, 4. Bokoy, 5. Bulguchhoy, 6. Vielkha-nekyi, 7. GIarchoy, 8. Gialai, 9. Gandaloy, 10. Merzhoy, 11. Muzhahoy, 12. Muzhgahoy, 13. Ojrghoy, 14. Ferghoy, 15. Khevkharoy, 16. TsIechoy.

Tapes not included in tukhums

1.Nashkhoy (Nakhsha, Charmahoy, Mozgara, GIoy), 2.Saloy, 3.Guhoy, 4.Guchinghoy, 5.Maisty, 6.Mulkyoy (Kottoy, Zhainhoy, Medarhoy, Bavarhoy, Baskhoy, Bengarhoy, Keyshtroy, GIezir-Kkhelloy , Khurkoy) 7.Peshkhoy, 8.Turkoy, 9.Khukoy, 10.Chinkhoy,

Names of peoples in Chechen

1. Abzoy, 2. Arceloy, 3. Gebertloy, 4. Zhugtiy, 5. Nogiy, 6. Orsi, 7. Cherkaziy, 8. Gezloy.

These ethnonyms are not names of teips. There are no foreign teips among Chechens, because According to Chechen laws, lei ("lay" - slave, farm laborer, non-Chechen) did not have the right to create a teip. There are units of non-Chechen branches/clans (dozal), which are families, not teips. So in Chechnya there are from 3 to 6 Jewish gars, among the Arien-Nokhchi, 2 Charadin gars and 1 Tsuntinsky.

Gezloy, Cherksi, Gebertloy, etc. - names of peoples in Chechen. Just like in Russian, “Noah’s people” are Chechens, but this does not make the Chechens become a “Russian teip”.

Nakh peoples:

Ingush, Chechens (Akkins, Kists), Batsbiy

Nakh-Dagestan peoples

Dagestanis: Avars | Aguly | Archins | Andean peoples: Andians Akhvakhians Bagvalians Botlikhians Karatinians Tindins Chamalins | Budukhtsy | Dargins | Rats | Laktsy | Lezgins | Rutulians | Tabasarans | Udi | Khinalug people | Tsakhur | Tsez peoples: Bezhta people, Ginukh people, Gunzib people, Khvarsha people, Tsez people

Nakh peoples:

Ingush | Chechens (Akkins, Kists) | Batsbians

1. Russian 2002 census

2. Data from the 2002 All-Russian Census

3. Based on materials from the League of Nations of St. Petersburg, the Assembly of Peoples of Russia

4. Chechens in the Middle East: Between Original and Host Cultures, Event Report, Caspian Studies Program

5. BC: Chechen lessons. 60 years ago, about 500 thousand people were deported to Kazakhstan

6. Russian Muslims are interested in the Russian Federation being accepted into the OIC, Kadyrov said

7. Refugees in Azerbaijan received humanitarian aid

8. Kadyrov will help Kyrgyz Chechens return to their homeland

9. The main result of the Caucasian war

10. Muhajirism or resettlement of Vainakhs to the Middle East

11. Yu. Veremeev. History of Chechnya in 1921-1941.

12. 1

13. Zarema Nbragimova Chechens in the mirror of tsarist statistics (1860-1900). - Space-2000. - ISBN 5-93494-068-6

14. Type (genus) and type relations in Chechnya in the past and present

Literature

L. Ilyasov. Chechen teip // Chechen Republic and Chechens: History and modernity: Mater. All-Russian scientific conf. - Moscow, April 19-20, 2005. M.: Nauka, 2006, p. 176-185 http://ec-dejavu.ru/c-2/Chechen.html

Alfred Koch. Analytics: “As I understand the Chechens. Four views”, September 3, 2005 http://www.polit.ru/analytics/2005/09/03/4vzglyada.html

V. A. Kuznetsov. “Introduction to Caucasian Studies” - Vladikavkaz, 2004

Nakh-Dagestan peoples

See also in other dictionaries:

CHECHENS - (self-name Nokhchi) - a people with a total number of 957 thousand people. Main countries of settlement: Russian Federation - 899 thousand people, incl. Checheno-Ingushetia - 735 thousand people, Dagestan - 58 thousand people. Other countries of settlement: Kazakhstan - 50... (Modern encyclopedia)

CHECHENS - (self-named - Nokhchi) - people in Chechnya and Ingushetia (734.5 thousand people) and Dagestan (57.9 thousand people). In total there are 899 thousand people in the Russian Federation (1992). The total number is 957 thousand people. The language is Chechen. Believing Chechens -… (Big Encyclopedic Dictionary)

CHECHENS - , Chechens, units. Chechen, Chechen, and (obsolete). CHECHENS, ov, units. Chechen, Chechen, m. The people of the North Caucasus living in Chechnya, within the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous SSR. Don’t sleep, Cossack: in the darkness the night Chechen walks across the river. Pushkin. Chechen... ( Dictionary Ushakova)

CHECHENS - , Chechens, units. Chechen, Chechen, and (obsolete). CHECHENS, ov, units. Chechen, Chechen, m. The people of the North Caucasus living in Chechnya, within the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous SSR. Don’t sleep, Cossack: in the darkness the night Chechen walks across the river. Pushkin. Chechen...

CHECHENS - , Tsev, units. Tsnets, Tsntsa. m. The people who make up the main indigenous population of Chechnya... (Ozhegov’s Explanatory Dictionary)

The Chechens are a Caucasian people of the Eastern Mountain group, who before the war occupied the territory between the Aksai, Sunzha and Caucasus rivers. Nowadays they live mixed with Russians and Kumyks in the Terek region, east of the Ossetians, between the Terek and the southern border... (Encyclopedic Dictionary of F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron)

CHECHENS - The most warlike Caucasian tribe. (

Since ancient times, Chechens have lived in the Central and North-Eastern Caucasus. The territory of the Chechen Republic is 17,200 sq. km. The population of Chechnya is over a million people. According to researchers, approximately one and a half million Chechens lives all over the world. Most of them live in the Russian Federation. Historians call the Chechen nation “the root part of the Caucasian race.” It is the most numerous of the.

Nakhchoy - Chechen people

The ancestors of modern Chechens appeared in the 18th century as a result of detachment from several ancient clans. The sources contain the name of the people - nakhchoy(i.e. people speaking the Nokhchi language). The ancestors of the Chechens passed through the Argun Gorge and settled on the territory of the present republic. Basic language – Chechen, there are dialect groups (Itumkalinsky, Akkinsky, Melkhinsky, Galanchozhsky and others). The Russian language is also quite widespread in the republic. Chechens profess the Muslim faith.

Folklore mythology was influenced by other ancient civilizations. In the Caucasus, the paths of many nomadic tribes and peoples of Asia, the Mediterranean and Europe crossed. The tragic pages in Chechen history caused enormous damage to spiritual culture. During the period of the ban on folk dances and music, and the holding of national rituals, the creative impulses of the Chechens were constrained by fears of falling into political disgrace. However, no restrictions and prohibitions could break or strangle the Chechen identity.

Chechen traditions

Hospitality

Hospitality among the Chechens it has been elevated to the rank of a sacred duty of every citizen. This tradition has historical roots. Traveling through mountainous terrain is not easy; at any moment, an exhausted traveler could hope for outside help. In a Chechen home you will always be fed, warmed and provided with overnight accommodation free of charge. The owner of the house could give the guest some home furnishings as a sign of respect. In gratitude, travelers presented the owner's children with gifts. Such a welcoming attitude towards the guest has been preserved in our time.

In the Caucasus, they treat their mother with special respect: they respect her, try to help in everything and listen to her advice. Men usually stand up when a woman enters the room.

With special trepidation men take care of your hat. It expressed a symbol of male honor and dignity. It is considered extremely humiliating if a stranger touches the papakha. Such behavior from a stranger can provoke a scandal.

Mountain upbringing

Younger family members behave modestly and do not interfere in the conversations and affairs of their elders. To engage in conversation, you need to ask permission. Until now, in a discussion of any issue, you can hear a Chechen utter the phrase: “Can I tell you...”, as if asking for permission to enter into a conversation. Such automatic behavior is an indicator of persistent and harsh upbringing from time immemorial. Excessive affection, caring for small children and anxiety associated with the whims of a child in public were not approved. If for some reason the child burst into tears, he was taken to another room where he calmed down. Children's crying and pranks should not distract adults from important matters and conversations.

In the old days, it was not customary to leave someone else’s things found in your house. In front of witnesses, the item was given to the village mullah so that he could find the owner. In modern Chechen society, it is also considered bad manners to take away someone else’s thing, even if found.

In a Chechen house

Kitchen

One of the revered delicacies is zhizhig galnysh, a simple but tasty dish. Wheat or corn dumplings are boiled in meat broth. Culinary chores are women's concerns, with the exception of funeral dishes that are prepared for funerals.

Wedding traditions

When a woman got married, she received her husband’s family with special respect and treated them with caring respect. The young wife is modest, quiet, incurious. Without special need, a woman should not start a conversation with older relatives. At a Chechen wedding there is even a funny ritual of “untying the bride’s tongue.” The future father-in-law tries to make his young daughter-in-law talk with jokes and tricks, but she clearly adheres to the people's rules and remains silent. Only after giving gifts to the guests was the girl allowed to talk.

Before the wedding, young Chechen women can communicate with their grooms only in crowded in public places. The guy always comes on a date first and only then the girl. Maiden honor is the pride of the groom and the subject of protection by the young Chechen, in whom hot Caucasian blood boils.

What is the population of Chechnya in the world?

- CHECHENS (self-name Nokhcho), people in the Russian Federation, the main population of Chechnya (1.031 million people), also live in Ingushetia (95.4 thousand people), Dagestan (87.8 thousand people), as well as the city Moscow (14.4 thousand people), Stavropol Territory (13.2 thousand people), Astrakhan (10 thousand people), Volgograd (12.2 thousand people), Rostov (15.4 thousand) people), Tyumen (10.6 thousand people) regions, Volga federal district(17.1 thousand people). In total, there are 1.36 million Chechens in the Russian Federation (2002). The total number is about 1.4 million people. An ethnic group of Chechens-Akkins lives in Dagestan. They speak Chechen. Believing Chechens are Sunni Muslims.

Chechens, like their related Ingush, belong to the indigenous population of the North Caucasus. Mentioned in Armenian sources in the 7th century under the name Nakhchamatyan. Initially, the Chechens lived in the mountains, dividing into territorial groups. In the 15-16th century they began to move to the plain, to the valley of the Terek and its tributaries Sunzha and Argun. Until 1917, Chechens were divided into two parts based on their place of residence: Greater and Lesser Chechnya. In the lowland areas the main occupation is agriculture, in the mountainous areas cattle breeding; Domestic crafts, production of cloaks, leather goods, and pottery are developed. - 1,267,740 people

Attention, TODAY only!

In the Chechen Republic, the dominant religion is Sunni Islam.

The process of Islamization of Chechens has seven stages. The first stage is associated with the Arab conquests in the North Caucasus, the Arab-Khazar wars (VIII-X centuries), the second stage is associated with the Islamized elite of the Polovtsians, under whose influence the Nakhs were (XI-XII centuries), the third stage is associated with the influence of the Golden Horde ( XIII-XIV centuries), the fourth stage is associated with the invasion of Tamerlane (XIV centuries), the fifth is associated with the influence of Muslim missionaries of Dagestan, Kabarda, Turkey (XV-XVI centuries), the sixth stage is associated with the activities of Sheikh Mansur, aimed at establishing Sharia, the seventh stage is associated with the activities of Shamil and Tashu-Hadji, who fought against adats, establishing Sharia, the eighth stage is associated with the influence of Shaikh Kunta-Hadji and other Sufi teachers on the Chechens.

The beginning of the mass spread of Islam among the ancestors of the Chechens dates back to the 14th century, although there is reason to believe that Islam diffusely penetrated among the Chechens in the 9th-10th centuries, which is associated with the penetration of Arab commanders and missionaries into the territory of the Chechens.

In general, the spread of Islam among Chechens is a complex, contradictory and centuries-long process of adaptation to ethnocultural reality.

Islam spread both by violent means - the conquests of the Arabs, and by peaceful means - through missionary activity. In Chechnya, and in general throughout Russia, the Sunni branch of Islam, represented by the Shafi'i and Hanafi madhhabs, established itself.

In the North-Eastern Caucasus (Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia), Islam has the form of Sufism, functioning through the Naqshbandiyya, Qadiriyya and Shazaliya tariqas, which have had a spiritual, cultural and political influence on many peoples of the region.

In the Chechen Republic, only the Naqshbandiyya and Qadiriyya tariqats are widespread, divided into religious groups - vird brotherhoods, their total number reaches thirty. The followers of Sufism in the Chechen Republic are Sunni Muslims who rely on the basic tenets of Islam, but at the same time follow Sufi traditions, honoring their ustaz, the sheikhs known to them, and the awliya.

Great place in religious activities Traditionalists are devoted to oral prayers, rituals, pilgrimages to holy places, performance of religious rituals - dhikrs, construction of ziyarat (movzaleev) over the graves of deceased ustaz. This centuries-old spiritual and cultural tradition in modern conditions, thanks to the activities of the President of the Chechen Republic and the Muftiate, is being actively revived, reaching its apogee.

Islam in Chechnya, due to its centuries-long adaptation to folk culture, is distinguished by its liberality and tolerance of other religious systems.

In the Chechen Republic, starting in 1992, a new teaching, unconventional for the region, began to spread - the so-called Wahhabism, which represents a religious and political alternative to local Islam.

The activities of the Wahhabis had a pronounced political nature and were directed against society and the state. The radicalism and extremism of Wahhabism was determined by the transition from one socio-political system to another, the collapse of the USSR, de-ideologization, democratic transformations, and the weakness of state power.

Currently, the activities of religious extremists, as well as terrorists, are being suppressed in the Chechen Republic.

A rapid revival of traditional Islam has begun, which is manifested not only in the construction of mosques and religious schools, but also in the spiritual education of youth. Traditionalists in their daily sermons call Muslims for unity, spiritual elevation, condemn drug addiction and many other sinful acts.

Chechen

representatives of the indigenous inhabitants of the Republic of Ichkeria, who traditionally lived in the mountainous regions of the northern slopes of the eastern part of the Greater Caucasus and, since the 19th century, also in the Terek Valley.

During historical development Chechens went beyond the feudal stage of development public life and slavery has scarcely been known, so the clan and clan relations at the heart of their society are still in full force. History of Chechnya in the 19th-20th centuries. This century can be called a period of constant struggle against colonization by Russia.

The Chechen people have strong feeling tribal collectivism. Its representatives always feel that they are part of a family, such (taipa). And intranet links are often more intense than other ethnic communities. They maintain relations with relatives of the fifth tribe. In this case, the feeling of belonging to Lenta prevails over national identity. Members of the clan are related by blood on the father's side and enjoy the same personal rights.

Freedom, equality and fraternity in it represent the main meaning of existence. A small number of Chechen pillars lived surrounded by stronger neighbors.

Absence complex shapes statehood among the Chechens greatly influenced the unity of the ribbons. Strictly protected by the legality of descent and the rights of such members, to preserve the glory and power which each of its representatives considered to be their personal responsibility. However, at the summit, the safety of each person depends on the fact that the insult or murder of any clan member does not go unpunished (the practice of blood dispute).

At the same time, each person must reconcile his actions with the interests of his family, because his relatives had to respond to his mistake.

This situation has caused such surprise to patriarchal and tribal morals as the inadmissibility of complaints about government bodies and appealing to their protection from offenders. Moreover, the role of tapas in the life of modern Czech society cannot be reduced for the following reasons: a) for each group, the armed forces are well equipped, organized, disciplined, subordinate to patriotic authorities in their actions; b) The solution of the tables largely determines the reasons for the clash between various security forces in Chechnya.

Czechs have many stereotypes about behavior in all areas of life. These stereotypes are based on strict respect for national traditions and traditions. For the majority, respect for tradition is hypertrophic, which is explained by their special education. From an early age, the Czech child was taught about the rules of the mountain bonton, whose ignorance is severely punished by older people.

Teaching is not carried out in the form of designations that are unacceptable to the child, but in the form of illustrative examples. Condemnation or approval of an act committed by a young person, youth or man is carried out directly in the presence of the child, so that he can hear and remember that he can publicly punish or, on the contrary, praise. The child, as he is, must evaluate various situations. Thus, he develops a sense of tactical, behavioral intuition, the concept of bonton, rather than reckless closure.

One more important feature The national psychology of the Chechen language is the recognition of the legitimacy of everyone, even the most cruel, who act as compensation for their dignity, life and honor of relatives (the practice of a blood dispute). Neglecting a relative was a shame for the entire family. The image of bloody revenge led to the objective historical reality of people's lives in conditions of constant interstate and external wars.

The inability to tire a person by killing or insulting a relative indicated the weakness of the family and thus exposed them to the danger of attack.

The emotional factor of the blood conflict was both an impression and an emotional feeling of the Chechens. You can also add your pride here, which does not allow a person to live peacefully when a Serbian is offended, because insulting one of the participants in the tape is tantamount to insulting all its representatives.

One of the oldest features of national character is patriotism. For them, love for the country of birth is a feeling that should be associated with true focus. Often patriotic feelings change into nationalism and chauvinism. Radical nationalists are more common among representatives of the mountainous (poorer) region, since among them there is a stronger national tradition. Joining the entire Chechen nation as a whole is poorly understood, since a sense of responsibility for one's own type dominates.

Since the deportations of the 1940s, Chechens have had a stronger psychological attachment to the Muslim world. The national specialty of the Chechens was hospitality. "If the guest isn't looking, it doesn't go well." These negotiations express the attitude of all people towards this tradition. The arrival of a guest is always awaited and there is no need to be afraid at home. He gives him Special attention- everything that is best in the house is for the guest. Although the visitor is under the protection of the host family.

For insulting a guest is the same as insulting a master.

how many people in the world are in Chechnya.

However, some criminals in Chechnya hid in court this way. During the Queen's time, the prevalence of cross-departmental media is widespread. The feeling is extremely powerful. Brothers are always faithful to friendship, sharing joy and sadness together. They are always ready to help each other, no matter who they are. This feeling is comparable to the tradition of blood conflict and the transition from generation to generation.

In multinational groups, Chechnya is independent. As a rule, they try to unite ethnicity. First, communication is characterized by isolation and vigilance. But when they get used to it, Chechens can take leading positions in the group.

Head of the anthropological type of Chechens

The Chechen people, like all other peoples, do not represent a single whole in racial terms. But like most peoples, they have formed a certain anthropological type, which is perceived as typical. This type undoubtedly belongs to the Western Asian race.

In this regard, Chechens are no different from others Caucasian peoples, the anthropological basis of which also relates to the race described above. Her character traits are well known. We are talking about strong people of medium and tall build with a non-elongated, short head shape, a pronounced aquiline nose and usually dark hair and eyes.

But even among the Western Asian race, which is distributed over a vast territory, it is necessary to distinguish subspecies, just as we do among the light Northwestern European race.

Among the peoples known to me with a Western Asian racial basis - northern Armenians, eastern Georgians with Pshavs and Khevsurs, Azerbaijani Tatars, a number of Dagestan peoples, Ingush and a small number of Kumyks and Ossetians - I also, in my opinion, discovered various options of this race.

To describe the Chechen Western Asian, I first want to express myself negatively.

His profile does not have those excessive Western Asian forms that, for example, are often observed among Armenians. A similar profile of an Armenian, approximately the one that was published by Lushan and was replicated in various books on racial studies, is not found among Chechens at all.

However, according to my observations, this type is rare among Armenians. The Chechen I photographed (images 5 and 6 on the right) has perhaps the most extreme Western Asian forms among his people. An ordinary Chechen anthropological type is depicted in photograph No. 7. This is, therefore, a completely moderate West Asian profile, albeit with a large, but still only slightly curved and not fleshy nose and a tolerably formed chin.

The latter is especially striking in comparison with image No. 5, in which, as in general with obvious Western Asian profiles, the chin recedes further and is itself flatter than what corresponds to our ideal of beauty. The profile in image No. 7 is not striking, it is balanced and pleasing due to its scope and bold, large outlines.

Also, the seated man on the right (image no. 8) falls into this category. His face can be called masculinely handsome without any restrictions. Anthropological forms that are often common are almost not reminiscent of a bird of prey of West Asian origin, but, on the contrary, have almost straight and thin noses and in which only short skulls are reminiscent of West Asian heritage.

These regular facial features were the reason for the former glory of Caucasian beauty and prompted Blumenbach to introduce the concept of the Caucasian race. Previously, especially during the era of the Caucasian Wars, when Bodenstedt was still in the Caucasus, the Caucasian peoples were too idealized, especially with regard to their physical beauty. Later, on the contrary, they went to the other extreme. Anthropological publications that depict the most extreme facial types are misleading. This applies, for example, to a photograph published in Gunther's racial studies.

It depicts an Imeretian from Kutaisi, who is perhaps the ugliest man that could be found in this city. In contrast to this, it must be emphasized once again that the Caucasian peoples, and among them especially the North Caucasians, are superior to their neighboring peoples in terms of physical beauty.

It is enough to move from Rostov towards the Caucasus and observe how at the stations the pure Caucasian faces with their large, straight features stand out from the vague Russian physiognomies.

As for the physique, I noticed that among the Armenians, eastern Georgians, Khevsurs and Dagestanis, people are mostly of average height and strong build, more often stocky than slender, but by no means tall; Some of the growth is very small, for example in some regions of Dagestan (Kazikumukh, Gumbet). In comparison, Chechens are conspicuous due to their height. It is enough to move from the last Khevsur settlement of Shatil to the Kist Dzharego and be amazed at the sharp anthropological change: among the Khevsurs there are stocky, wide figures, among the Kists there are tall, slender, even elegant, appearances.

This observation of mine was also confirmed by Radde's messages (see list of references, No. 36).

I noted the same difference between the Ichkerians on the one hand and the Andians and Avars, especially the Gumbetians, on the other.

Slimness sometimes seems excessive. In other places, such figures would probably be called frail.

In vain! Since the shoulders are usually wide, only the hips are narrow. Because of this, the body gets an unusually firm, elastic, and sometimes slightly relaxed look. This look is further emphasized by wearing a Circassian coat on the plain.

In the mountains this is less noticeable, since there they usually wear a heavy sheepskin coat covering the body, with the exception of Melchista, where again the Circassian coat is mainly common.

The corpulence which I have observed among the Armenians and Eastern Georgians, both men and women, especially in old age, is almost entirely absent; slimness and thinness are common.

Chechens seem tall only in comparison with their neighbors; the average figures are hardly comparable to the North German ones.

I only saw people taller than 1.85 m with confidence only twice. One was a Kist (meaning a highlander) from Melkhista, the other, the tallest Chechen in general, was the already mentioned grand vizier of the former Emirate - Dishninsky. By the way, this circumstance played an important role in increasing his authority among ordinary mountaineers.

He was a completely aristocratic personality, combining in himself all the advantages of his race, as well as, of course, its disadvantages.

In the above, the racial basis of the Chechen people was called Western Asian, but with the same right it can be called Dinaric.

I met Dinarides in large numbers among Serbian prisoners of war during my travels through Carinthia and Styria (historical regions of Austria) and if I compare them with the dominant race among the Chechens, then I do not see any significant differences to speak of in contrast to the Dinaric race. then a special variety of Central Asian.

For Armenians and some Dagestanis, this may correctly speak of a special sub-branch of the Central Asian race, but only in the sense that the distinctive features of the Dinaric race among them are too overly expressed (thereby alienating them from the Dinarides); the shape of the head tends to the shape of a “tower skull”, the nose is unattractively large, the height is partially below the standard. This is not typical for Chechens in general; it is also not typical for Ingush and Ossetians, and also, according to the generally accepted idea, for Circassians.

Thus, only with these reservations do I classify the Chechens as a Western Asian race.

The special position of the Chechen Western Asian will still be proven by the color of his hair, eyes and skin. People with pure black hair and very dark eyes, like Armenians and partly Georgians, are not often found among Chechens; in any case, there is no such thing that both characteristics coincide.

Therefore, we can only talk about an anthropological type, which is generally dark. Most often, the hair on the head is dark (and also black), while the eyes opposite are brown or a color that is difficult to describe with precision. It can probably be called light brown, with a small admixture of green. I observed clear, translucent light brown eyes more often in women than in men.

But what first strikes the traveler is the large number of blondes and light-eyed people, mostly the latter of the above. It is difficult to say which tone predominates: both gray and grey-green eyes are common, and pure blue, sky-blue eyes are also common, which could not be clearer in Northern Germany.

Blonde hair is somewhat less common than light eyes.

But here the reason is a very strong gradual darkening. Among children there are significantly more fair-haired children than among adults, and dark-haired adults assured me that they had blond hair in childhood. I noticed early graying in men; Usually thirty-year-olds have noticeable gray hair. Surely one of the reasons is the constant wearing of a hat. Men with shaved heads are also not uncommon.

Learning about hair color is naturally made more difficult by this custom. And in general, you need to go spend the night with people to see uncovered heads; people with bare heads open air not to see: it doesn’t matter whether it’s a man, a woman or a child.

The color shade of the blond is perhaps less consistent with the dull blond of the eastern race, and more similar to the blond of the northern race, tending towards golden, although in its pure manifestation I did not observe golden. I have also seen red-haired people many times; their eye color was light brown.

More often than blond hair, there are blond beards, and I remember the brown-red tone, the same in men with dark hair and brown eyes.

Beards are abundant and even, and are worn with a certain precision. Flowing red beards like Barbarossa are also common, and it should be noted that henna is not used.

But most men only wear a mustache.

The skin of light Chechens is delicate and fragile; young girls have a beautiful complexion. In men, the face is reddened by the wind and bad weather, and not dark, a circumstance especially characteristic of the Nordic race.

The body is white in the best sense. I once observed this in Melchist. A certain number of kists (meaning mountaineers) were busy transporting wood along the Argun; they themselves, standing in the water, transported untied tree trunks, towed them in the right direction, holding long poles in their muscular fists and guiding the logs between the boulders washed by the foam of the waves.

Although they were not dressed, they were not embarrassed by our approaching Georgian column. Wooded slopes, a seething mountain stream, and undisguised heroic images of forest rafters created at that time an atmosphere of rare romance, which I will always remember, precisely because of its clearly expressed Nordic character. Similar cases never happened to me in the rest of the Muslim Caucasus. Extreme scrupulousness prevents men from appearing naked. They also dislike the sight of at least partially naked bodies of others; I was convinced of this many times when, in the winter of 1919/1920, I lay seriously ill for a whole month in a private house in Botlikh (Andean Dagestan), I could not persuade a single man to help me in any way.

When I tried to get up, everyone left the room despite my objections. I don't think this is due to any superstitions, such as fear of infection.

The freer views of the Chechens are also reflected in the freer position of women, who move freely without covering themselves with a veil, who are allowed to speak openly with men, which is hardly observed in internal Dagestan.

For more accessible description Chechen blond, I want to compare him with fair Northern Europeans.

S. Paudler, in his work on light races, clearly distinguished between the Dalish Cro-Magnon race and the usual dolichocephalic (i.e., long-headed) light representatives of the northern race. Of these two races, only the latter is suitable for comparison. Light Caucasians are similar to her because of their smoother and evener lines, fuller lips and more rounded eye shapes.

Hard, coarse facial features, which for example are often found among residents of Westphalia (a region in Germany), are absent, judging by my observations. Not to mention the extreme Dahl anthropological types from Scandinavia published by Paudler.

As far as I know, they are not found among other Caucasian peoples. Comparison with light-colored North-Western European dolichocephals is permissible only in relation to the color and shape of the face.

In the structure of the skull, Chechen blondes do not differ from their brunette fellow countrymen. And here and there the same short, straight skulls, the same aquiline noses. The man in the middle of image No. 8 combines all the color features of the light type in a pure form, he was more than 1.80 m tall, but he had a short head shape even for Chechen proportions. There are also more elongated forms of the skull with a slight convexity at the back of the head, but they are also common among those with dark hair and brown eyes.

Still, the length of the skull never reaches the size of ordinary Nordic dolichocephalic skulls. Nevertheless, the tall Chechen blonds with their long, narrow faces and their whole demeanor really give the impression of a fair northerner. In Maista and Melkhist it is very easy to study skulls, since in the crypts there you can find a large number of them. I also found long skulls there (dolichocephalic skulls).

But of course I did not take exact measurements, this is only an approximate measurement by eye.

This slender, brachycephalic (i.e., short-headed), big-nosed race, found collectively in both dark and light forms, is so predominant among the Chechens that the remaining existing component racial parts cannot change the overall picture. The dominant one among other anthropological types is similar to the Alpine race. That is, most often we are talking about dark, short people with a shapeless physique and a rough skull.

Images No. 5 and 6 show a representative of this race, who still has relatively regular facial features, especially a rather graceful nose, while in general the faces of the Alpines seem ugly. Judging by my observations, the Chechen Alpine lacks the rounded shapes characteristic of the Alpines of Central and Western Europe.

The body is rather toned and angular, which is most likely due to the lifestyle. I cannot say that I noticed a significant number of mixtures between the high Western Asian and Alpine anthropological types.

Both coexist rather simultaneously: I don’t remember meeting a tall Chechen with a bulky head and a short nose and a flat face profile, or, on the contrary, a short and stocky one with a Western Asian shape of face and skull. Both men in image #5 and 6 are photographed sitting and appear to be the same height. In fact, the Western Asian on the right was a head taller than the Alpine on the left.

It seems to me that the part of the Chechens who belong to the eastern race, to which the Russians basically belong, also seems insignificant.

I also did not notice any obvious Mongolian racial characteristics, which are, in principle, possible, given the early proximity to the Kalmyks and the current proximity to the Nogais. These signs are found in the northern part of Avaria, and only in the form of particularly prominent cheekbones. I have never seen the Mongolian eye shape.

As for the issue of the geographical distribution of individual anthropological types, I can only speak with some degree of confidence about the distribution of blonds.

And in this regard, I can say that individual regions show great differences.

Without a doubt, in the western part of Chechnya the percentage of blondes is higher than in the east. In the west there are areas in which the population can be called mostly light. If we talk about eye color, there is no doubt about this statement, but also the number of people with blond hair, skin and eyes will be almost 50%.

First of all, this is the territory along Chanty-Argun starting from Melkhista to Shatoi.

Especially in these parts, I was surprised by the large number of generally Nordic appearances, especially since blond hair is combined with exceptionally good growth. In Maisty, the district neighboring Melchista, this was less noticeable* (* among the children I noticed some clearly Jewish facial features).

Because of the regular facial features, I also remember the population of the Khocharoy valley. And I already wrote about Shatoi girls. Next we should call the upper reaches of the Sharo-Argun, although to a lesser extent than Shatoy.

In Chaberloy, I was only in the eastern and western villages, Chobakh-kineroy and Khoy, where I did not notice a significant number of blondes, although Cheberloy was described to me by some Chechens as a territory with a mostly fair population.

In general, it must be said that some well-traveled Chechens were well aware of the anthropological features of a particular region, such as the high stature of the inhabitants of Melkhista. My observations about the distribution of the fair population were generally confirmed by them. When I asked about the reason for the differences, they answered me without much hesitation that in such and such an area there are more blondes, and in such and such there are more brunettes. The disappearance of the light element in the east is especially felt in Southern Aukh, and after crossing the Andean watershed in Dagestan territory, the dark element already dominates, both in Gumbet and Andi.

At the same time, the number of rude and ugly faces is increasing. This is most clearly manifested in the village of Benoy. I would also like to add that among other Chechens and especially among the Gumbetians who buy corn from them, the residents of Benoy have a rather bad reputation.

The fact that the light element predominates in the west is especially interesting if you look at the history of the settlement of the territory.

It turns out that in the territories inhabited, according to legend, there are primarily more blondes than in the lands later developed in the east. I don’t want to get lost in conjecture, but the thought suggests itself that the reason must be sought in the later colonization of the eastern regions, and, as already mentioned, in the possible absorption of other populations.

On the plain, I did not notice a clear predominance of the light or dark anthropological type.

Here, too (as in the mountains), tall, slender people with aquiline noses predominate.

Among the Caucasian peoples known to me, undoubtedly, the largest number of blondes is among the Chechens.

There are fewer and fewer Russians in Russia, but more and more Chechens and Ingush

In ethnographic works, as well as in the literature on the Caucasus, they mainly write about the Ossetians. In principle, the reason is clear. Ossetians are an Indo-Germanic people and during the era of Indo-Germanic research they received a lot of attention. In fact, the percentage of blondes among Ossetians is hardly higher than among Chechens.

Still, I got the impression that the features and facial expressions of Ossetians are more similar to European ones than those of Chechens and Ingush. The Ossetian hotel owners in Vladikavkaz, blondes, really bothered me with the completely unfamiliar language coming from their lips; It seemed to me that the Germans were in front of me.

The fact that the Ossetians are mostly Christians may also have played a role; to the same extent, the reason may also be that they have a larger intelligentsia than their eastern neighbors. Among the Chechens there are apparently only 2-3 people with a university education, while among the Ossetians, despite their smaller numbers, there are several dozen.

This stronger thirst for knowledge seems to be related to the Christian faith.

Von Eckert, who anthropologically studied 70 Chechens (list of used literature, No. 12), wrote at the end of the publication that everyone had dark hair. This conclusion is very unusual, assuming that the readings are made on the basis of accurate observations. But we are talking exclusively about the residents of Aukh, that is, the Chechen east.

I also included a section of traditional medicine here; perhaps this information is also of some anthropological interest.

The conversation is about the procedure for treating headaches by Chechens.

Full text in German - http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewconten … xt=r_gould

Nokhchalla - Chechen character, Chechen traditions

Mutsuraev Timur

This word cannot be translated. But it can and must be explained. "Nokhcho" means Chechen. The concept of “nokhchalla” is all the features of the Chechen character in one word. This includes the entire spectrum of moral, moral and ethical standards of life for a Chechen. One could also say that this is the Chechen “code of honor.”

A child in a traditional Chechen family absorbs the qualities of a knight, a gentleman, a diplomat, a courageous defender and a generous, reliable comrade, as they say, “with mother’s milk.” And the origins of the Chechen “code of honor” lie in the ancient history of the people.

Once upon a time, in ancient times, in the harsh conditions of the mountains, a guest who was not accepted into the house could freeze, lose strength from hunger and fatigue, or become a victim of robbers or a wild animal.

The law of the ancestors - to invite into the house, warm, feed and offer overnight accommodation to the guest - is observed sacredly. Hospitality is “nokhchalla”.

Roads and paths in the mountains of Chechnya are narrow, often snaking along cliffs and rocks. Having a row or arguing can lead to falling into the abyss. Being polite and compliant is “nokhchallah.” The difficult conditions of mountain life made mutual assistance and mutual assistance necessary, which are also part of “nokhchalla”. The concept of “nokhchalla” is incompatible with the “table of ranks”. Therefore, the Chechens never had princes or slaves.

“Nokhchalla” is the ability to build relationships with people without in any way demonstrating one’s superiority, even when in a privileged position. On the contrary, in such a situation you should be especially polite and friendly so as not to hurt anyone’s pride.

So, a person riding a horse should be the first to greet someone on foot. If the pedestrian is older than the rider, the rider must dismount.

“Nokhchalla” is friendship for life: in days of sorrow and in days of joy. Friendship for a mountaineer is a sacred concept. Inattention or discourtesy towards a brother will be forgiven, but towards a friend - never!

"Nokhchalla" is a special veneration of a woman.

Emphasizing respect for the relatives of his mother or his wife, the man dismounts his horse right at the entrance to the village where they live.

And here is a parable about a highlander who once asked to spend the night in a house on the outskirts of a village, not knowing that the owner was alone at home. She could not refuse the guest, she fed him and put him to bed. The next morning the guest realized that there was no owner in the house, and the woman had been sitting all night in the hallway by a lit lantern.

While washing his face in a hurry, he accidentally touched his mistress’s hand with his little finger. Leaving the house, the guest cut off this finger with a dagger. Only a man brought up in the spirit of “nokhchalla” can protect a woman’s honor in this way.

"Nokhchalla" is the rejection of any coercion.

Since ancient times, a Chechen has been brought up as a protector, a warrior, from his boyhood. The most ancient type of Chechen greeting, preserved to this day, is “come free!” The inner feeling of freedom, the readiness to defend it - this is “nokhchalla”.

At the same time, “nokhchalla” obliges the Chechen to show respect to any person.

Moreover, the further a person is by kinship, faith or origin, the greater the respect. People say: the offense you inflicted on a Muslim can be forgiven, for a meeting on the Day of Judgment is possible. But an insult caused to a person of a different faith is not forgiven, for such a meeting will never happen. To live with such sin forever.

Wedding ceremony

The Chechen word “wedding” means “game”. The wedding ceremony itself is a series of performances that include singing, dancing, music, and pantomime. Music sounds when fellow villagers, relatives, and friends go for the bride and bring her to the groom’s house. There are other performances that take place at this stage of the wedding.

For example, the bride's relatives delay the wedding train by blocking the path with a cloak or a rope stretched across the street - you need to pay a ransom to get through.

Other pantomimes take place already in the groom's house. A felt carpet and a broom are placed in advance on the threshold of the house. When entering, the bride can step over them or move them out of the way. If she tidies up neatly, it means she’s smart; if he steps over, it means the guy is out of luck.

But the bride, festively dressed, was seated in a corner of honor by the window under a special wedding curtain, and then she was given a child in her arms—someone’s first-born son. This is a wish for her to have sons. The bride caresses the child and gives him something as a gift. Guests come to the wedding with gifts. Women give pieces of cloth, rugs, sweets, and money. Men - money or sheep.

Moreover, men always give the gift themselves. And then - a feast on the mountain.

After the refreshments there is another performance. The bride is brought out to the guests, from whom they ask for water. Everyone says something, jokes, discusses the girl’s appearance, and her task is not to talk back, because verbosity is a sign of stupidity and immodesty. The bride can only offer a drink of water and wish the guests health in the most laconic form.

Another performance game is organized on the third day of the wedding.

The bride is led to the water with music and dancing. The attendants throw cakes into the water, then shoot them, after which the bride, having collected water, returns home. This is an ancient ritual that is supposed to protect a young woman from the merman. After all, she will walk on water every day, and the merman has already been lured with a treat and “killed.”

On this evening, the marriage is registered, in which the trusted father of the bride and the groom participate. Usually the mullah, on behalf of the father, gives consent to his daughter’s marriage, and the next day the bride becomes the young mistress of the house. According to an old Chechen custom, the groom should not appear at his own wedding. Therefore, he does not participate in wedding games, but usually has fun at this time in the company of friends.

Attitude towards a woman

A woman who is a mother among Chechens has a special social status.